Hello everyone:

The Field Guide is taking the week off so that I can bring you some good news: My book, The Roast Penguin Chronicles, has just launched from Compass Rose Press. It’s part memoir, part history of the human experience of Antarctica through a “culinary” lens. The book is built from a century of remarkable stories of life on the ice, from the sagas of early exploration up through the 20th century and recent years, including my own near-decade on the ice. It is, as I write in the Prologue,

my love letter to that storied past and to all that Antarctica has fed me: beauty, wonder, friendship. It is the weaving of my own small story within the wilder tales of hunger and survival from an incredible cast of characters.

I’ll tell you more about it, and then offer you the table of contents to peruse and the Prologue to read.

If you’re a new reader of the Field Guide, or a long-time reader less interested in a book about Antarctic history, hold tight: I’ll be back next week with another Field Guide essay on the beauty and strangeness of the transformed Earth. For now, you can visit the archives (last year at this time I published “The Community of Air”), or simply scroll down past the Roast Penguin Chronicles excerpt to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Before I began writing the Field Guide four years ago, I was writing primarily about Antarctica, where I worked from 1994 to 2004. As readers of the Field Guide know, I fell deeply in love with the ice - the place, the history, the people - and am still very much influenced by my experience there. It provided a view of the world that informs all I do here contemplating the Why?, How?, and What next? of the Anthropocene.

Over the next several years, I published a small pile of literary essays about the astonishing Antarctic landscape, and I also wrote one short, fun essay toying with the idea of the “history of Antarctic cuisine.” It was a distraction, a quick side project, while trying (and failing) to write a poetry-infused book-length lyric essay about Antarctic history, landscape, and aesthetics.

A culinary history of the ice continent, it turns out, is a wonderful way to understand what it means to be a human in a place that has no human history, way out on the edge of the livable Earth. You may have heard of Ernest Shackleton, or the race to the South Pole between Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott, or the decades-long quest by modern science to understand the role of Antarctica in a warming climate, but Antarctic history is so much richer than that. It is, from a culinary angle, a collection of remarkable tales of starvation, scurvy, penguin-eating and, eventually, bad cafeteria food, spiced occasionally with great feasts, ingenious cooks, and a deep appreciation for sustenance in a landscape that wants to kill you. Unlike most food histories, The Roast Penguin Chronicles is a book of beautiful stories rather than of beautiful recipes.

I published the original essay in a small literary food magazine and forgot about it, which is the fate of nearly every literary essay ever published. But then one day I was very surprised to receive an email from a university press asking if I was interested in turning the essay into a book. I was, and three years later - in 2012 - the book came out. It received several awards, had some great reviews (most notably in the New York Times), but didn’t sell a lot of copies.

Now, with a new publisher, a new title, and several months of work editing the manuscript, adding some new memoir sections to frame up the chapters, and redesigning the book, we can cheerfully announce the launch of The Roast Penguin Chronicles: Hoosh, Scurvy Days, Sleeping with Vegetables, and Other Adventures in Antarctic Cuisine. If you or anyone you know is intrigued by food writing, culinary histories, stories of exploration and adventure, unusual memoirs, or just good writing about a wonderful place few people have seen, please take a look.

I’m happy to be involved with Compass Rose Publishing, a new venture whose business model is defined by its support for, and alliance with, the hundreds of independent bookstores around the U.S. and beyond. Check them out, and be sure to support your local bookstores.

With no further ado, then, here are the front and back covers of the book, the Table of Contents, and the complete Prologue for you to read. I’ll add some photos as well. Enjoy.

Prologue - A Recipe for Something

A day before I flew by Twin Otter from Ross Island into the Transantarctic Mountains for a three-month deep field assignment, my friend Robert Taylor led me quietly into the McMurdo Station kitchen and surprised me with a dozen loaves of his exquisite bread. A slender, soft-spoken baker with a penchant for mischief, he knew he was helping me escape to the hinterlands with some of the best food in the United States Antarctic Program (USAP).

Into my knapsack went bundles of illicitly made olive, sweet potato, and plain sourdough, moist but with a firm crust. “This is beautiful, Robert,” I said. “How can I repay you?”

“You can’t,” he said, smiling sweetly. “Just have a good time, and when you come back tell me some stories.”

Ask anyone for stories of Antarctic cuisine, and they’re likely to go as blank as the ice continent itself. Antarctica lies somewhere beyond their imagination, or exists as the strange white mass smeared across the bottom of their cylindrical-projection world map. Often they’ll confuse it with the Arctic, where polar bears and Santa Claus roam the sea ice. With a little prompting, they may at least know Antarctica as the media depict it—the frigid home of penguins, icebergs, and undaunted scientists.

For me, it has been both a second home and a dreamlike otherworld of ice. For eight Antarctic summers, I lived and worked in the starkest landscape on Earth. I slept on a mass of ice larger than India and China combined, woke up flying over glaciers that overflow mile-high mountains, and ate meals in a tent shaken so wildly by katabatic winds that I thought its destruction was imminent.

Antarctic ice is three miles deep in places. The growth of sea ice around the continent each winter is the greatest seasonal event on the planet, while the largest year-round terrestrial animal is microscopic and plant life is confined to a few stony pockets within the 0.4 percent of Antarctica not covered in permanent snow or ice. Ninety percent of the planet’s ice sits in Antarctic ice caps so hostile to human life that nobody stood on them until the twentieth century. The existence of Antarctica, the only significant realm actually discovered by colonizing Europeans, was not proved until 1820, and the continent’s coastline was not fully sketched until the late 1950s.

You may ask, therefore, if there is really such a thing as a venerable Antarctic cuisine. In a word, no. Since the dawn of time, as far as we know, no human ate so much as a snack in the Antarctic region until Captain James Cook and his frostbitten sailors nibbled on biscuits as they dodged icebergs below the Antarctic Circle in 1773.

Seal hunters made the first brief Antarctic landings by the austral summer of 1819–20, but no one sat down for a regular meal on the continent until 1898. Then, as now, what visitors to the Antarctic—and we are all visitors—sit down to are imported meals. There is no Antarctic terroir. The land does not provide, cannot provide, because there isn’t a square foot of arable soil on the entire 5.4-million-square-mile continent in which to plant a garden.

There have been, however, two sources of Antarctic cuisine: the flavors people bring with them and the flavors of the Southern Ocean, meaning the flesh of seals, penguins, and sea birds raising their young on the Antarctic shoreline. Antarctic culinary history comprises a mere century of stories of isolated, insulated people eating either prepackaged expedition meals or butchered sea life. In recent decades, with kinder, more complex menus, each nation’s research base enjoys a limited version of its own home cuisine.

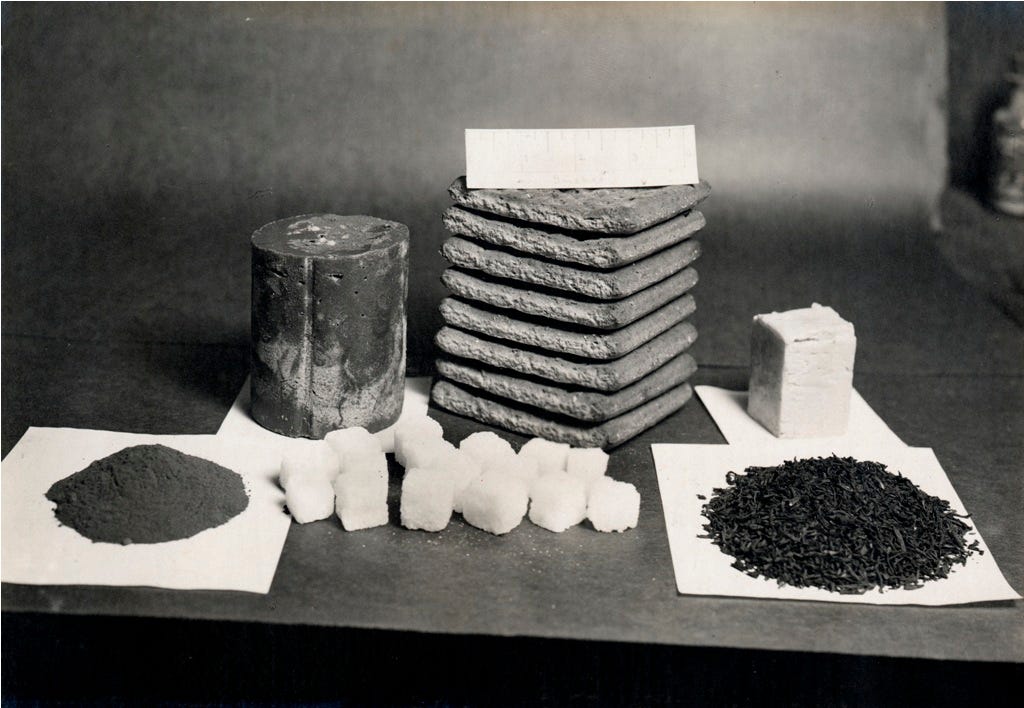

If the mother of Antarctic cuisine was necessity, its father was privation. Hunger was the one spice every expedition carried. In the words of Lieutenant Kristian Prestrud of the 1910–12 Fram expedition, “To a man who is really hungry it is a very subordinate matter what he shall eat; the main thing is to have something to satisfy his hunger.” Rations for sledging expeditions looked and tasted much alike.

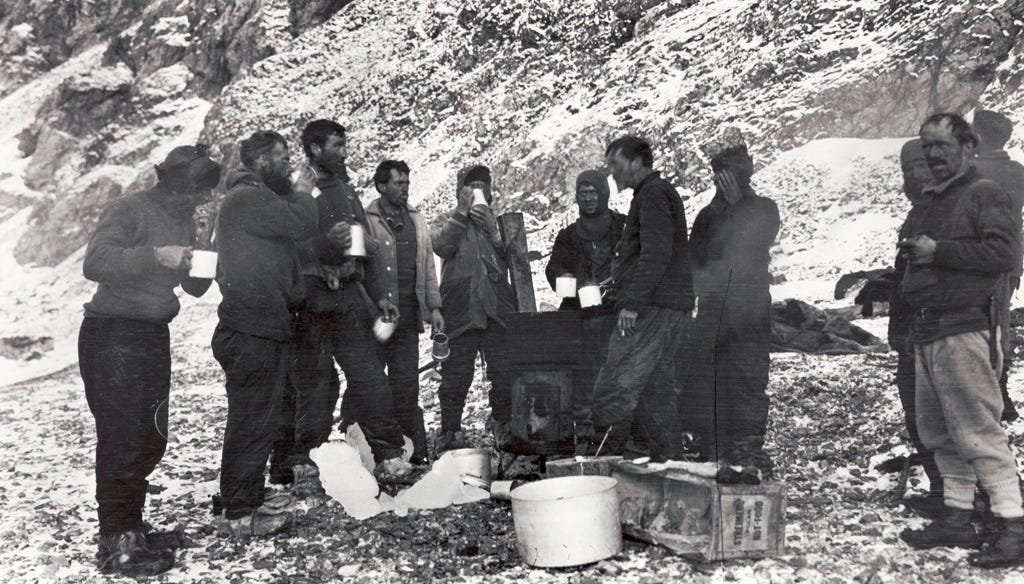

Sustenance ruled over sensitivity. Thus, the heroes and stoics of Antarctic history scribbled in their journals about seal steaks and breast of penguin, about pemmican and biscuit crumbs boiled in tea. About dog flesh and caches of pony meat. About “hoosh,” the bleak Antarctic soup of meat and melted snow. About scurvy and dying hungry.

Properly defined, hoosh is a porridge or stew of pemmican and water, often thickened with crushed biscuit. Ship’s biscuit, also known as hardtack, had fed sailors for centuries. Pemmican is a Native American high-energy food made of dried, shredded meat mixed with fat and flavored with dried berries. Antarctic pemmican differed in substance—commercial beef and beef fat rather than wild meat—and appearance—compacted, uniform, measured blocks.

The word hoosh is a cognate of hooch, itself a corruption of the Tlingit hoochinoo, meaning both a Native American tribe on Admiralty Island, Alaska, and the European-style rotgut liquor that they made. Hooch became common slang throughout North America for bootleg liquor, particularly during Prohibition, while for British polar explorers in both the Arctic and Antarctic, hoosh came to mean the meat stew of the ravenous.

“Hoosh—what a joyous sound that word had for us,” said Frank Worsley, captain of the Endurance. And indeed, the onomatopoeic sound of it, like the whoosh of the Primus stove bringing their stew to a boil, must have been music to their ears. All of which shows how Antarctica’s sad state of culinary affairs has been framed by a truly rich history on this terra incognita.

Here, at the bitter end of terrestrial exploration, where year-round occupation preceded the invention of the microwave oven by only a few years, food has rarely had a more attentive, if helpless, audience. Cold, isolation, and a lack of worldly alternatives have conspired to make Antarctica’s captive inhabitants desperate for generally lousy food.

My Antarctic captivity—quite voluntary—occurred between 1994 and 2004. I worked various jobs in the USAP (waste management specialist, fuels operator, cargo handler, field camp supervisor) as part of the U.S. community from which scientists ventured out to gather data.

Occasionally, I worked more closely with these researchers, but like most Antarctic residents, I had little to do with science. This surprises most people to whom I tell my Antarctic stories. They hear in the media that Antarctica is lightly populated with teams of bold researchers, funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to bring home information for the benefit of humanity. There is some truth in this, certainly, as the entire population of the continent in the busy, summer research season (nearly five thousand) is smaller than that of a small town back home and there are many bold and useful science projects being done by brilliant scientists under difficult conditions.

What few people know, however, is that only 20 percent of residents are there for scientific research. The rest of us create and maintain the infrastructure that makes this science possible. In Antarctica, where children are as rare as flowers, it takes a village to raise a scientist.

By far the largest “village” in Antarctica is McMurdo, the USAP hub on Ross Island in the Ross Sea, 2,400 miles due south of our deployment point in Christchurch, New Zealand. (The second largest base, the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station—with up to 240 summer residents—is also an American installation.)

Most Antarctic bases are populated by ten to one hundred multitaskers. McMurdo, however, bustles with up to twelve hundred people in the austral summer months (October through February, when the northern half of the planet is in winter). The vast majority of them are dining-room attendants, carpenters, plumbers, general assistants, shuttle drivers, and so on.

They bake the bread, clean the dormitory and office toilets, operate bulldozers, handle radio communications, and shovel snow. For the most part, my experience was their experience. Although by the end of my decade I’d had my share of excitement in the Antarctic wilderness, most of my time was spent in McMurdo, working ten hours a day and six days a week with friends in a workaday triangle between dormitory, job, and cafeteria.

And though it seems strange to say, this mundane experience makes my perspective on Antarctica unusual. While most books from the Antarctic have been written by explorers, journalists, historians, and scientists, those notables have made up only a small minority of Antarctica’s inhabitants. Even though many of the working residents have stayed longer and seen more, over the last century, only a few support workers (out of tens of thousands) have published books.

In the history of the USAP, the largest community on the ice, Jim Mastro (Antarctica: A Year at the Bottom of the World, 2002) and Nicholas Johnson (Big Dead Place, 2005) were the first to give voice to our neglected majority. These books look beyond the harsh weather and cute penguins of a typical Antarctic travelogue. Jim, Nicholas, and I write from the wealth of experience gathered during long austral stints, returning year after year to a community rich in oral history and deeply connected to the strange Antarctic landscape.

We share our occupation of the barren landscape with the ghosts of early exploration. Men (and they were all men for the first eighty years) from four different expeditions during the early twentieth century struggled across the volcanic gravel McMurdo has since bulldozed for its roads and buildings.

The wind-worn wooden shed on Hut Point—just beyond our massive cargo pier—is a remnant of Robert Falcon Scott’s 1901 Discovery expedition, complete with rusting tins of meat on the interior shelves and a ninety-year-old seal carcass outside. As if in response, across town from Hut Point and looming over McMurdo like the final note in a fugue, a large jarrah-wood cross standing atop Observation Hill commemorates the deaths of Scott and his men on their 1912 Terra Nova expedition. On that final journey, starvation, malnutrition, and severe weather laid the men down just one hundred and thirty miles south of the hut and eleven miles away from their next cache of food.

In between Discovery and Terra Nova, Sir Ernest Shackleton led his Nimrod expedition across Hut Point en route to the South Pole, which, in the end, lay just ninety-seven miles beyond his grasp. He struggled and starved his way back to the hut, just in time to set a shed ablaze as a signal to his northbound ship. Later, in 1915, the men of the Aurora (the second ship of Shackleton’s Endurance expedition, who planned to cross the continent to Ross Island via the Pole), passed under the shadow of Ob Hill as scurvy and storm claimed three of their lives.

Some forty years later, the modern age of Antarctic exploration began in earnest and the roots of McMurdo were put down in a massive operation by the U.S. Navy. Despite storm and cold, thousands of burger-fed sailors from several steel ships moved the makings of a tent city, and eventually a small permanent prefab town, onto the ice-free shores of the southward-pointing Hut Point peninsula of Ross Island. McMurdo became the southernmost port on Earth, and Antarctica was at the doorstep.

During my time on ice, our banter around the dining tables in McMurdo’s galley (as the navy-built cafeteria has long been called) often includes reference to these outsized stories of Antarctic exploration. The early tales of men like Shackleton, Scott, and Roald Amundsen, and the navy’s hard-won settlement of the ice, remind us of the harshness of the place in which we now enjoy soft-serve ice cream.

Douglas Mawson, an Australian who knew more about Antarctic suffering than most, said that, in the midst of his deprivation, “cocoa was almost intoxicating and even plain beef suet, such as we had in fragments in our hoosh mixture, had acquired a sweet and aromatic taste scarcely to be described . . . as different as chalk is from the richest chocolate cream.” Are we Mawson’s descendants or his antithesis? Either way, we revel in our cozy existence in a place that once sponsored such raptures over the benefits of starvation.

As on other frontiers, the successes, the failures, and the noble and ignoble exploits of our pioneers become essential narratives for those of us who have settled into their footprints. As we find opportunities to leave McMurdo for more remote parts of the ice, and then sense the same human insignificance and fragility they experienced amid the Antarctic austerity, their storied past provides a literary and historic language by which to understand our experience.

This book is my love letter to that storied past and to all that Antarctica has fed me: beauty, wonder, friendship. It is the weaving of my own small story within the wilder tales of hunger and survival from an incredible cast of characters. And The Roast Penguin Chronicles is a culinary history of a continent without its own cuisine. Why? Because no matter where we are on Earth, food is how we taste the world, past and present.

My little exploit, the one Rob’s bread was meant to feed, took place in the austral summer of 2001–2. I had been asked to take the lead in a new two-person camp in the Transantarctic Mountains, where we would build and maintain a runway on a minor seven-mile-wide thread of ice called the Odell Glacier.

I was told to pack everything we’d need for the full one hundred days on the Odell, because no one knew if there would be a resupply plane or helicopter available to send out an extra stick of butter. Still reeling from the task of planning three hundred meals—plus snacks—ahead of time, I was particularly pleased when Rob led me between the oversized cauldrons and gleaming bread racks of McMurdo’s industrial kitchen toward his secret cache of sourdough. Looking surreptitiously behind us, he slipped into the walk-in freezer to grab two large bags.

I just stared at him. “This is real food, Robert. We may have to make an altar out of cardboard or ice or something and worship this while we munch on granola bars.”

Rob rolled his eyes and smiled. “I hope you find a better use for it than that, Jason.”

“I’m sure we will. Let’s see, twelve loaves over a hundred days, that’s . . . a loaf every eight days. Oh man, we are all set. This is great. Thank you so much.”

“Of course. I’m happy to help. Just be careful out there and let me know how it goes.”

I knew I’d have stories for Rob. Something was bound to happen. Two guys, three months, four tents, one glacier, and fifteen boxes of food. It was a recipe for something.

I’ll be back next week with another Field Guide essay.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

A little belated, but Happy World Rewilding Day, which was on March 20th. Take a look at the Global Rewilding Alliance, and support rewilding work in whatever place(s) you care for.

The latest “Owl in America” post from

does an excellent job laying out the legal tactics and cruelty of the new Trump administration from the perspective of an environmental lawyer, and she closes the piece with a good-news update on the Klamath Dam removal and subsequent wetland restoration work, despite efforts by the administration to cut funding and staff.From

and , “The Relegation of Nature Writing,” Bryan’s latest post both celebrating his 10,000th subscriber and exploring what it means to be a nature writer in a culture that is increasingly detached from nature.From the Post, an update on which states are still handing out money (state and federal) for clean energy updates to your home, like heat pumps, heat pump water heaters, induction stoves, EV charging station, and solar panels.

From the Guardian, an op-ed from the ACLU and Greenpeace on the terrible $660 million dollar lower court decision in North Dakota against Greenpeace for its support of the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota-access pipeline. The ruling, they say,

could have wide ranging consequences on first amendment rights in the US. By attempting to hold Greenpeace liable for everything that happened at Standing Rock, the case attempts to establish the idea that, for any participation in a protest, you can be held liable for the actions of other people, even if you’re not associated with them or if they’re never identified. It’s easy to see how this win for Energy Transfer could chill speech and silence future protests before they even begin.

From Nautilus, “Ping, You’ve Got Whale,” a new AI-powered whale detection system is being built to help prevent ship strikes, one of the leading causes of whale mortality.

Also from Nautilus, “March of the Mangroves” provides an overview of the consequences of mangrove forests on the move as the planet warms.

From The Overpopulation Project, a working paper that seeks to frame a new, clearer definition of global overpopulation. They’re looking for feedback. Here is the definition they’re offering. To me, at a glance, it’s sensible and solid, but I’m not a fan of the term “ecosystem services” and I think “sharing the landscape fairly” is a bit vague:

Human societies, or the world as a whole, are overpopulated when their populations are too large to preserve the ecosystem services necessary for future people’s wellbeing and to share the landscape fairly with other species.

Congratulations on the re-release! Your voice is so needed at this time.

Dear Jason,

Congratulations on your amazing tireless efforts of your book!, which I see as a timely balm for your devoted readers & to the world during these unthinkable unprecedented times. Like all your works, the prologue was SO moving and beautifully & thoughtfully written with a spirit of unmatched integrity. Know your every written word is a heartfelt blessing to those fortunate enough to cross your path - and Mother Earth is especially grateful for the Gift of you.🤍🌎