Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

As much of Canada burns this summer, a small and seemingly unremarkable lake in Ontario has been chosen by a committee of geologists to represent the Anthropocene. That is, it has been selected among several candidate sites around the globe to mark the moment in geologic time that, due to planetary-scale human activity, a new epoch in Earth history began.

The mantle bestowed upon this lake is not meant as a brief honor or symbol, but an enduring reference point intended to last centuries, and to take its place among similar geological reference points that look back hundreds of millions of years in the stony encyclopedia of Earth history.

Why this lake? What story does it tell? Let me first step back and offer a broad thought that’s been haunting me recently: Human history is now Earth history. It is one the most absurd things we can say about this moment in time, but it is also one of the most true.

We’ve been an unremarkable chattering primate for nearly all of our species’ history, just another lump of charismatic megafauna in a world run by microbes, insects, and plants. But when a new kind of human society invented tools to erase landscapes, oppressed and made war upon traditional cultures, concocted an ecological Ponzi scheme we call “constant growth,” built an artificial intelligence we call corporations and fueled them with hundreds of millions of years’ worth of stored energy, and permitted the population to grow like bacteria in a warm pond, we (its descendants) suddenly find ourselves living on a transformed Earth.

Our unprecedented struggle in this and subsequent generations is to undo much of the harm. The task is possible, but we have our work cut out for us. We must be fast, and we must think of it as the central mission rather than an extracurricular activity.

Industrial society has altered more than 70% of the planet’s terrestrial surface, cut in half the global biomass of vegetation, and decimated wild animal populations so intensively that every land mammal we can think of (pandas, polar bears, elephants, and porcupines) and those we can’t (tenrecs, polugos, fossas, saigas, and jerboas), if lumped together, add up to just 4% of all mammal biomass on the continents. Humans and our livestock make up the rest.

Gone is the relative stability that ruled the chemistry of the atmosphere, the currents and temperature and acidity of the oceans, the ice at the Poles and in the mountains, the free flow of rivers, the depth and fertility of soils, and the distribution and population of species in nearly every habitat on Earth. There is scarcely an Earth system whose safe boundary we haven’t violated.

Our impacts grow in intensity, scale, and weirdness. The soils and waters of the planet are now infused with plastics and other synthetic chemicals. Radioactive isotopes from nuclear bombs dusted the Earth like the iridium fallout from the dinosaur-killing asteroid 66 million years ago. Near-Earth orbit is as cluttered with mechanical debris as the bottom of the oceans, and the low-frequency radio waves used to communicate with submarines shape the Van Allen radiation belts that surround the planet.

With a web woven by ships, planes, and the commerce that drives them, we’ve shifted and introduced such a great mass of animal and plant species from continent to continent – the invasives and exotics in your backyard, the crops in your fridge – that we are effectively reuniting the continents in an anthropogenic Pangaea.

In recent years, some geologists have begun to contemplate a name for what we’ve done: the Anthropocene, the “New Age of Humans.” Here’s how I introduced the concept 118 essays ago in my second Field Guide post:

The basic idea of the Anthropocene is this: Humans have already transformed the Earth significantly enough that we can safely predict that millions of years from now our impacts will be visible in the planet’s sedimentary rocks. Those impacts – our “geological signature” – are not so much to the stony foundation of the Earth’s surface, though that’s happening, but to all of life on Earth, which is itself a geological force. If we rewrite the book of life, we rewrite geology too.

Like all else that is human, then, this planetary transformation is a story. From the perspective of Earth history, we have been an infinitesimally minor character visible only for a moment among a few billion years of life. Our rise to center stage may be like that of a red-shirt Star Trek character stepping confidently but fatally onto the surface of a new planet… or it may be only an awkward blip in a noble human existence that, once corrected, will thrive for millions of years hence.

From the perspective of this new society, we’re the hero of the story, altering life on Earth to provide an ever-increasing bounty (longer lives, better shelter, more productive agriculture, etc.) to our fellow humans through our wizardry and hard work. From the perspective of the rest of life on Earth, though, we’ve become an invader, a toxin, a bulldozer, a baited hook, and a wielder of flame and pavement.

Which means that the story of the Anthropocene must be told honestly, and the role of hero defined clearly. Being the hero is vital to us, because we’re an intensely social species whose consciousness is built on narrative. The great work being done by activists and policy-makers to right the ship of culture and steer it toward a responsible relationship with the community of life is, in effect, an effort to redefine the human hero. The wizardry and hard work necessary now to benefit our fellow humans is the restoration of planetary-scale functioning ecosystems. Anything less is biting our own baited hook.

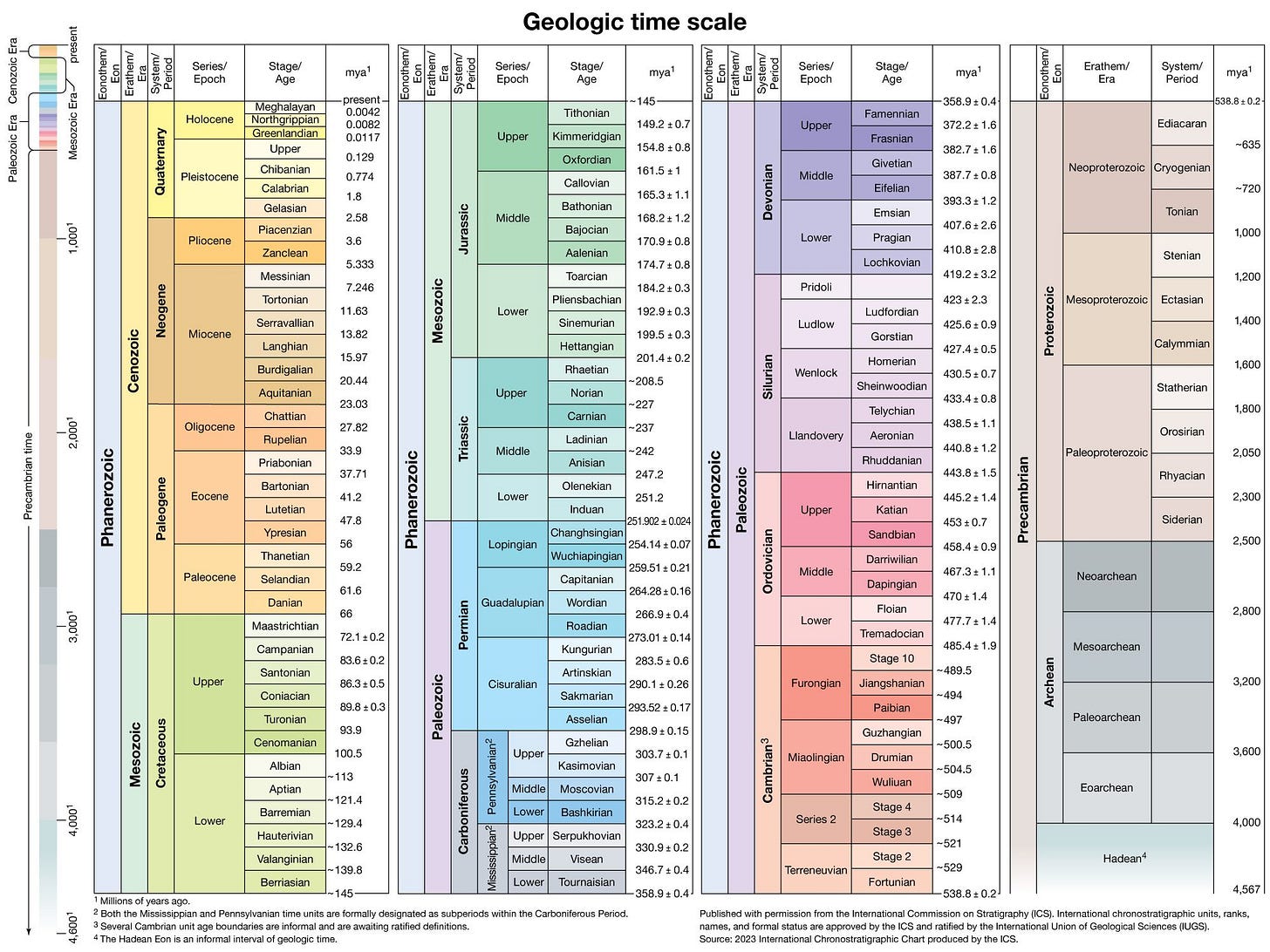

But geologists are professionally leery of culture and its fleeting stories. They wrestle with deep time, and many of them have been uncomfortable with this idea that a new geologic epoch should be named for the flurry of human activity that has lasted mere decades or centuries, which don’t exist at the geologic scale. They’d rather debate the origin of, say, the Cambrian Period, with a margin of error of a few million years. But the evidence for the Anthropocene has been strong enough that the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) was created in 2009 to determine 1) the validity of the idea and, if confirmed, 2) when it began and 3) which place on Earth best represents it.

This third task, the naming of a representative site – a so-called “golden spike” marking the beginning of a particular geological time span – is essential to the deliberative process of naming periods of Earth history. These boundaries between ages are often differentiated by some visible catastrophic change in the fossil record (e.g. asteroid > dinosaurs).

Because they are meant to be a long-lasting scientific reference point, these sites are meticulously chosen, and a literal metal spike is driven into the appropriate layer of stone. Of course, other than the odd bit of plastiglomerate washing up on beaches, the Anthropocene hasn’t created a layer of sedimentary stone yet. Thus, the chosen site will include sediments which, millions of years from now, should reflect the global transformation we’ve made.

The spike’s proper name is a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP), defined as “an internationally agreed upon reference point on a stratigraphic section which defines the lower boundary of a stage on the geologic time scale.”

There are a couple ironies in the relationship between the time scale and the Anthropocene. The first I noted two years ago in that early Field Guide essay:

it’s worth noting that the entire concept of the chart, like much of science, is a function of the Anthropocene. It is neither an accident nor an irony that the same species which measures geologic time by periodic catastrophe has now created its own catastrophe to mark geologic time. These are two functions of a single skill set unique to humans: the willingness and capacity to reimagine nature.

The second irony is the “golden spike” itself, which is an Anthropocene metaphor, named for the ceremonial final spike driven to complete the U.S. transcontinental railroad in 1869. You might as well call it a nail in the coffin, the stitching together of space and time by technology and a profit-driven culture eager to alter the lush and diverse world.

The AWG isn’t looking for a mere example of the transformed world. Those are everywhere, in infinite variations. A glance out (or in) your window will find one. Nor are they looking for a symbol. Thus, a golden spike will not be driven into the commercial frenzy of Times Square, the lost wetlands under Shanghai, the gaping maw of an open pit mine, or the silent blankness of a bleached reef. The AWG has been looking for a distinct marker of “a clear, abrupt, and global transition from the previous Earth epoch to something new,” as its chairman described it.

They’re looking, in other words, for a witness.

They narrowed the search down to a dozen sites, including a Polish peat bog, an Australian reef, a Japanese bay, and an ice core from the Antarctic Peninsula. I don’t have the time or space here to dig into what differentiated each of these sites from the others, but you can read excellent summaries of each at the Anthropocene Curriculum, and a fine overview of the final nine sites by Yale e360.

This brings us to the winner – Crawford Lake in Ontario, Canada – and the story it tells. Selected this past July, the lake is a lovely, sheltered, quiet, and calm place.

The lake is located within Crawford Lake Conservation Area, listed by Canadian authorities as a Regionally Environmentally Sensitive Area and an Ontario Area of Natural and Scientific Interest. It is also part of a UNESCO site, the Niagara Escarpment World Biosphere Reserve.

(Learning about the lake has been an opportunity to expand my vocabulary. Prepare yourself for these Scrabble-worthy beauties: karstic, meromictic, varve, monimolimnion, and mixolimnion…)

What makes Crawford Lake special? It’s a small lake, but a deep one, deep enough that the bottom layer (the monimolimnion) does not mix with the upper (the mixolimnion). This lack of mixing defines it as meromictic, and has ensured that the bottom of the lake remains undisturbed. The lake’s unusual depth (nearly 80 feet) is due to a sinkhole in the karstic landscape – water-soluble limestone riddled with caves and tunnels – and at the bottom are exquisitely-defined layers of sediment. These layers record with precision each year’s deposit of pollen, soil, organics, and pollution. To be precise, these layers are called varves, and each varve is actually an alternating seasonal layer of sediments, and the year-by-year story they tell is very much like those told by tree rings and ice cores.

The final crucial piece of the Crawford puzzle is that there are no burrowing organisms in the lake bed sediment to rummage around in the varves and disrupt the story. But it’s not just the story of the past the AWG is concerned with. At the current rate of deposition, the lake won’t fill up for 30,000 years, which means it has the potential to act as a living archive, documenting the turbulent and vital centuries to come, one layer at a time, for many generations.

What story does Crawford Lake tell so far? The tale is told vertically, in core samples from the lake bottom. When Yale e360 reported on the AWG’s selection, they put it this way:

While the lake may appear serene and undisturbed, the sediments beneath its waters hold the remains of Indigenous settlements, European colonies, logging, farming, burning fossil fuels, and testing nuclear weapons.

Several centuries of human history – Indigenous settlement, colonial settlement, and industrial impacts – rest atop a deep baseline of natural sediment. For two centuries, starting in the late 1200s, a community of several hundred Attawonderon or Wendat people lived next to the lake. (The park has created an interpretive program for this history, including the construction of three longhouses. Also, Crawford Lake may soon be renamed in acknowledgement of its Indigenous history.) Their history is recorded in the pollen of corn and sunflowers, the fungal spores of a corn disease, and the increase in nutrients to the lake corresponding to hundreds of nearby humans.

After the 15th century departure of the Wendat/Attawonderon people, the lake’s varves reverted to baseline. But in the early 1800s, European colonizers set up shop nearby, adding to the lake sediment charcoal, agricultural pollen, logging/lumbering debris, and signs of increased nutrients and erosion. But it was in the mid-20th century, during the Great Acceleration of human impacts across the globe, that Crawford Lake’s story becomes a planet’s story.

The Anthropocene story can certainly be traced back to the start of the industrial revolution, or even thousands of years back to the transition of human societies to large-scale agriculture and city-states. But the geologists want a clear and permanent signature, not a cultural milestone. So the Great Acceleration, with its dusting of radionuclides (like plutonium-239 and cesium-137), heavy metals, soot and fly ash, a change from intact to fragmented ecosystems, and other indicators of our planetary transformation, has become the point of no return. The mud beneath Crawford Lake captures all that.

How much does the naming of this little quiet lake as the golden spike matter to you and me? Not too much, I think. It feels in some ways about as relevant as a patient with a rare disease learning about the physician for whom the disease is named. But it’s an opportunity to tell a story about our story, and to acknowledge the care with which a small group of very particular scientists have gone about the task. And it’s important to whatever extent it helps us rewrite the Anthropocene story. There, we can say as we point to Crawford Lake, that’s a witness to what went wrong.

Soon, though, perhaps the burned-fossil-fuel carbon particles will stop falling in the same way that plutonium-239 and cesium-137 stopped falling after test ban treaties were signed. And maybe in a decade or three the terrible megafires will stop burning in Canada. And the lake will witness that too.

An excellent article by the Post on the Crawford Lake story quotes Catherine Tammaro, a Wyandot artist and faithkeeper, who is descended from the people who once lived next to the lake. She considers the lake a living being, and calls it “Kionywarihwaen,” a Wendat name meaning “where we have a story to tell.” Tammaro didn’t like seeing scientists extracting sediment cores from the lake bed, but thought it might serve a greater purpose:

“It’s like a surgical operation,” she said. “It’s painful, but we recognize that it should be done … because it may help prevent further climate disaster by adding to our understanding of how humans have had an impact on the Earth.”

The AWG has completed its last big task. Their choice, and the committee’s work generally, now goes the larger International Commission on Stratigraphy, who that recent Yale e360 article referred to as “the timekeepers of Earth’s history.” If the Anthropocene is formally recognized as an epoch in geologic history by the International Union of Geological Sciences, then the lake’s role in our story will be set literally in stone.

But there’s so much of the Anthropocene story that the lake cannot tell. A glance back at the litany in my opening paragraphs here, or a glance out the window of your home or car, will show just how limited the Crawford Lake story is. It’s only a signature, after all.

That there remains such a vast untold story, one invisible in the strata of Crawford’s sediment, is a function of chattering primates trying to communicate at the geologic scale. We are mayflies trying to read encyclopedias. Human history may suddenly be Earth history, but that doesn’t mean for a moment that industrial society truly thinks or comprehends at the scale of eons, eras, or epochs. We are not creatures of the Long Now, though a few of us have always aspired to be.

Still waters run deep, says Crawford Lake. There are still waters within us, waters that ripple uncomfortably with the burden of our industrial firestorm of destruction, waters that motivate us to rein in and undo some of the harm, but they do not run so deep as to fully understand the future we’ve already wrought, much less the one beyond it.

We are fully capable of rewilding and restoring much of the lush planet that has nurtured us, but even with our best efforts there will be a cost to the community of life that will echo down the coming centuries, millennia, and tens of millennia. There are the extinctions we know, the extinctions we don’t know, and the disruptions of Earth systems that are far easier to unbalance than to rebalance. Some of these changes, whatever becomes of us, will be visible millions of years from now.

I can write these sentences, but I cannot see the shape of the echoes. This is not only because any future is a darkness, but because even at our end of the scale I have no idea when, or how much, planetary-scale rewilding and restoration will occur. In other words, I don’t know when we, as a civilization, will hear the story in the lake and hear behind it the greater, more tragic story whose ending we are still writing.

If human history is Earth history, then the good decisions we make now are more consequential than any we’ve ever made. This is another way of saying the stakes in this hero’s journey are terrifyingly high.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the Guardian, an important essay from the always-brilliant Rebecca Solnit on the problem of climate doomers spreading doubt and disinformation about our ability to solve the climate crisis. Solnit is full of insights: “I wonder sometimes,” she says, “if it’s because people assume you can’t be hopeful and heartbroken at the same time…” It’s worth quoting her at length:

I don’t know why so many people seem to think it’s their job to spread discouragement, but it seems to be a muddle about the relationship between facts and feelings. I keep saying I respect despair as an emotion, but not as an analysis. You can feel absolutely devastated about the situation and not assume this predicts outcome; you can have your feelings and can still chase down facts from reliable sources, and the facts tell us that the general public is not the problem; the fossil fuel industry and other vested interests are; that we have the solutions, that we know what to do, and that the obstacles are political; that when we fight we sometimes win; and that we are deciding the future now.

From

at , an incredibly important reminder that our destruction of the land has been as important to overheating the climate as our greenhouse gas emissions. His three-part series, “Millan Millan and the Mystery of the Missing Mediterranean Storms,” is a brilliant and beautifully-written narrative explanation of how this “missing leg” of the climate story has been written out of public discourse by the IPCC and others. I’ll be writing more about this, but highly recommend you read Lewis’ account.From

at , a great explainer comparing the value and virtue of nuclear power in the energy landscape:Nuclear power is much cleaner and safer than fossil fuels, but it’s also not nearly as good as renewable energy, which is equally clean and safe but much faster and cheaper to build.

From the Guardian: Need a breather from contemplating the chaos here on Earth? Looking outward to galaxies and beyond, says this article, we’d do well to stop imagining the physics of the universe like some kind of elaborate clock. Instead, “We should think of the cosmos as more like an animal than a machine.” I love that.

From Mother Jones, a long-form narrative piece about rafting the Green River in Utah in order to observe the long-term, government-sponsored, wanton destruction of the Uinta Basin by oil and gas production. Drilling there had decreased in recent years, but the war in Ukraine has driven up prices and Joe Manchin’s poisonous add-on to the Inflation Reduction Act (requiring more oil/gas leasing on public land in exchange for clean energy permits) has turned back the clock.

From Grist, the possibility that a little-known independent federal agency could bring much-needed regulation to the fraudulent morass of carbon credits.

From the Guardian, the astonishing and unprecedented decline in Antarctic sea ice is still a mystery. There’s too much chaos in the south polar climate system to be sure the problem is directly related to our heating of the climate, but it’s certainly a good guess. Read the article to understand how scientists are thinking through the problem.

From the Times, a new study has found that a vegan diet is responsible for 75% less greenhouse gas emissions than a diet that includes more than 3.5 ounces of meat per day (that’s less than a quarter-pounder). Better yet, a vegan diet uses 75% less land, 54% less water, and destroys 66% less biodiversity.

From E&E News, rebates for home energy efficiency upgrades (buildings and appliances) are one step closer to reality. Federal guidelines have been released. Now it’s up to the states to submit their plans and the DOE to approve them. Some states should be offering rebates to consumers by the end of the year.

From the Intercept, the story of how Wildlife Services, the U.S. federal agency tasked with killing millions of animals every year, largely at the behest of the livestock industry, poisoned 14-year-old Canyon Mansfield and killed his dog with an M-44 cyanide bomb. These are indiscriminate predator killers, and should be banned. “Canyon’s Law,” a bill to ban M-44 cyanide bombs on public land, has been refiled in both the House and Senate. Read this article and contact your representatives and senators to support the bill. Read more about it from Predator Defense and join the campaign against M-44s by the Center for Biological Diversity.

Now for the sake of getting a conversation started, let me expand on my criticisms. No one, absolutely no one is advocating that we sit in sack cloth and ashes and do nothing -simply because we have done our homework and see the disastrous trendlines. In fact, it's we dispairers who are the least likely to sit and do nothing to try and slow down and mitigate the changes. We live in the fact-based community. The dreamers who think that humans will come up, inevitably, with some constellation of fixes and everything will be all better, are the ones most likely to sit on their hands. Being lectured that big oil and the fossil fuel industry are the villains and all it takes is political action to rein them in and, presto chango! everything will be hunky dory, does no good. We ourselves created that industry- they didn't come to earth in flying saucers! We created them, nurtured them, sustain them and must take responsibility. We ourselves are the villains and always have been and likely always will be. There are limits, hard evolutionary limits, to human intelligence and the way we handle and prioritize problems and the Anthropocene, the Pyrocene, are the outcome of humans as change-agents limited by their own biology. I see no reason, short of reengineering ourselves, not to believe that we wont keep repeating the same mistakes over and over.