Hello everyone:

My apologies for this second email, but in the first version the two blocks of lines from Walt Whitman were scrambled, and Walt deserves better than that. Enjoy!

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Perhaps the best metaphor for the passage of time is a river. We feel the movement of time from one instant to the next, from one experience to the next, but every moment has its own fluid texture: faster, slower, rougher, smoother, aimed straight for the horizon or disappearing around the bend… Sometimes, time dilates and we’re paused in an eddy, either feeling stuck or joyfully lost in the moment.

We observe this changing texture over moments, hours, days, years, and decades, and we call it life. What we call memory is a history of the river. This all sounds philosophical, but I mean it literally. Run your mind back over recent hours and map out the different textures of the moments in which you yawned, was annoyed by your neighbor’s car alarm, delighted in a cardinal at the feeder, coughed up smoke from Canadian wildfires, remembered a lost loved one, saw the sun breaking through the clouds, grimaced at the news from Ukraine, and began reading these opening paragraphs. Time flows erratically.

I want to ask, though, when you picture this river, are you floating down it or perched on the bank (like Hesse’s Siddhartha) observing its passage? Either way is fine. It’s a metaphor, and you can inhabit it anyway you like.

But let’s get rid of the metaphor. Where does that leave us? Time, without its metaphor, is felt as some mysterious compelling force that accompanies us between birth and death. After that, who knows? Here among the living, we perceive it as a measure of experience, but that might just be our peculiar consciousness giving meaning to the changes all around us, changes in the rocks and clouds and light, and changes in the behavior of cells in our bodies and in the bodies of our fellow species. We give transformation a narrative when it might only be the universe breathing.

The physical world, too – the “space” in space and time and the “where” in Where are we? – is some vibrating plane of reality that seems to be traveling down the same river but is more likely merely changing shape, like a flickering fire. Matter is neither being made nor destroyed. Everything is energy. The sunlit butterfly and the Grand Canyon are made of the same stuff. So are you, and you’re watching it all happen.

Together, space and time make up a fabric into which our existence is woven. That’s our best guess, at least. Honestly, though, science can only account for about 5% of all matter in the universe. What we call “dark matter” (~25%) and “dark energy” (~70%) are the placeholder names we use to guess at the footsteps we hear approaching from all around us in the dark forest. Whatever the truth may be, it’s a safe bet that the other 95% of the universe will redefine what we call life and its context.

Here on Earth, then, we live in mystery. The awareness of that mystery is what we call awe.

Or we can call it wonder, or being overwhelmed, or feeling a quiet joy. We could even call it ignorance, though that word has become an insult in a world that confuses information for wisdom and that insists modern humans know exactly what they’re doing. We don’t, which is why in this era of too many people doing far too much for too little reason, letting down our guard and smiling at the mystery is really, really good for us. In fact, it’s what we evolved to do.

It's hard to talk about the necessity of awe without sounding precious. But that’s my task here. And it shouldn’t be too hard, because on some level we already know that a steady diet of awe is as necessary to our well-being as food and water. Without it, life is a windowless room in which meaning can only be constructed rather than found. We know we need more than that.

Awe is a clear lens through which we see the real world as it is: astonishing, strange, dangerous, beautiful, and equally vast and intricate beyond measure. Many of you may call that clear lens God, but neither spirituality nor religion are required. We only need to pay attention.

When was the last time you felt the world fall away as you experienced, for a moment, a sense of wonder or awe? Hopefully, it was yesterday, or earlier today. If not, why not?

Because awe is merely awareness, not some heightened state that you have to work to achieve. The work to experience awe, if we want to call it work, is only to quiet the chatter and strip away the clutter long enough to merely open our eyes (and other senses) to perceive some fragment of the vast mystery.

I’ve opened this essay with an attempted sketch of the whole mystery, but our experience of it is by necessity only of fragments, each one beautiful, strange, and powerful. The daisy and the bee, the cloud and the sky, the radish and the garden, the birth and the child, or the death and the parent. We live in relation to awe in all of our relationships, familial and ecological. It’s there, if we allow ourselves to feel it as those relationships deepen in meaning.

A child asked Walt Whitman about a fragment, and his answer underpins one of the world’s great books of poetry:

A child said What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands; How could I answer the child? I do not know what it is any more than he. I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green stuff woven. Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord, A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropt, Bearing the owner's name someway in the corners, that we may see and remark, and say Whose?

I was inspired to write about awe this week because of a long-form exploration of the importance of awe in Noema magazine. Among the many things to learn in the piece, there’s this: When we feel awe, we become happier, less self-involved, more kind, more connected to others and the natural world, and healthier.

One researcher has found that the regular experience of awe is an excellent predictor of low levels of inflammation. She said in a subsequent TED talk that

I used to see a walk in nature or a trip to the museum as a luxury I could rarely afford in my busy life. Now I see these experiences as essential to my mental and physical health.

The Noema piece is built around a profile of Dacher Keltner, head of the Greater Good Science Center (GGSC) at UC Berkeley and the author of the new book, Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life. (Keltner was also a consultant for Pixar’s hit animated movie, Inside Out.) One of his more interesting studies involved two groups of students, one of which was asked to gaze into a eucalyptus grove for one minute. The other group was asked to stare at a nearby building. A questionnaire for both groups immediately afterward suggested that the eucalyptus-gazers were significantly less egocentric:

Upon being asked to imagine how much they should be paid for their participation in the study, they asked for significantly less money. Finally, in response to a staged accident in which the experimenter dropped some pens, the eucalyptus group was observed to react more helpfully. A short burst of awe seemed to leave participants feeling more altruistic, more collaborative and less entitled.

Keltner emphasizes that awe is often a social phenomenon. We are a deeply social species, and to see that you don’t have to look farther than the political and ecological cliffs we’re willing to jump off if everyone else is doing it too. Awe can be the path to ruin, if we’re in thrall to the wrong magic. On the bright side, you can feel awe in action in those beautiful moments when we sing or pray together, or when we witness human achievement as a crowd. We are “swept up” and “carried away.”

Moreover, Keltner suggests that our physiological reactions to awe (e.g. goosebumps, tears) are social signals that draw us together. I would add that we become open-hearted when reminded of the magic of existence. It’s harder to maintain resentment while watching a meteor shower. And we all know intuitively that we can reduce or reset our social anxieties by taking a walk and experiencing a bit of awe.

Awe doesn’t need to be intense or dramatic. I doubt the undergrads were awestruck by the eucalypts, or even concluded their minute by saying, “Awesome!”, that most abused of sacred words. So, how does Keltner define awe? The Noema article is a bit fuzzy on his thesis, but I think the two main concepts, “perceived vastness” and “the need for accommodation,” come down to this: We feel astonished or overwhelmed by what we’re witness to, and have to broaden our mind to take it in.

Staring at the branches of a eucalyptus grove for one minute, however, is not about experiencing something earth-shaking or mind-boggling, so really what we’re talking about is feeling a connection to something greater, however we define it. We can feel awe when falling in love, imagining the cosmos, witnessing powerful art, hiking on mountaintops above the clouds, feeling fear in a thunderstorm, singing in a choir, taking psychedelics, strolling in a forest, studying with a magnifying glass or microscope the intricacies of an insect or blossom, or any one of a million ways we might connect with existential realities outside our self. The magic can be small and quiet, and often is.

Like the dawn chorus of birds outside our windows, awe is a wake-up call. If we’re listening, we can hear it every day.

Talking about awe this way blurs the definition enough that we might as well be talking about wonder or meditative curiosity. There’s a diversity of awe that ranges from sacred to satisfying. And that’s fine for me. Categories and definitions aren’t the point here. Awe is about the value of experiences that take us out of ourselves and into the fabric of existence. We have to step out of the self to cultivate it.

So, the possibility of awe is all around us, and the more we make it a daily habit the happier and healthier we’ll be. For my purposes here in the Field Guide, I’ll note also the importance of Earthlings using their capacity for awe to motivate the necessary transformation of society. Arguably, the lack of active awe for the natural world in our disconnected and distracted daily life underpins much of the catastrophe that’s unfolding.

But it’s less our fault than the fault of those who’ve built the junk-food quality aspects of civilization, giving us occasional fireworks while blotting out the depths of the night sky. As I often say, we’re complicit but also trapped. Awe is one path out of the trap. “In every man's heart,” wrote Christopher Morley, “there is a secret nerve that answers to the vibrations of beauty.” And as a recent and surprisingly philosophical Times article on the Grand Canyon put it,

At any point in time, the world we see is somewhere in between being created and being destroyed. It is seldom static, which is why, if there are things we cherish about the present, it’s on us to preserve them…

I’ve been lucky and privileged enough to spend an unusual amount of my life in astonishing places, using much of my early adulthood to make the river of time into a lake I could explore at my leisure… In particular, my years in the lunar landscapes of Antarctica transformed my view of life. Awe was a constant force, equal to gravity.

The experience burned an awareness of the mystery into my brain. Behind everything, beautiful or mundane, is timelessness and emptiness, like the unoccupied 99.99% of an atom. I learned on the ice that time and space eventually feel like tricks of our imagination, and that existence is somehow both fragile and extraordinarily durable. (FYI, this information turns out to be more useful for writing than for a resumé.)

So yes, I’ve been lucky and privileged to see as many truly wild places in the world as I have, but these have also been choices. In fact, the life I’ve led has been a set of linked choices that valued time over money, quiet over noise, restraint over ambition, etc. It’s a financially tenuous life path, but perhaps no more so than those of most Americans living with debt and hectic, hyperscheduled lives.

Even now, in a quiet rural life on the Maine coast, I am surrounded by an abundance of beauty at the nexus of forest and sea, and I take daily opportunities to observe the abundance. Heather and I have always taken long walks and paid attention to the life around us, but ever since she took her year-long Maine Master Naturalist Program course, the abundance has multiplied tenfold as we go deeper and deeper into the lives of plants and animals. My journeys are shorter now, but no less rich or rewarding.

I was also inspired to write about awe this week because of how

at beautifully described his 20-year quest to find the rare Bog Elfin butterfly in a Vermont spruce bog. See my write-up below in the curated Anthropocene news, and check out Bryan’s post. You’ll see that the butterfly, the biologist, and the spruce bog are made of the same stuff.You can take a deeper dive into the nuances of awe, including a description of several studies exploring its mechanisms, in “All About Awe”, an article in Psychological Science.

Finally, then, I’ll get back to Walt Whitman, who reminds us that life and death beget life and death, and so perhaps neither is any more present than the other. Matter is neither created nor destroyed, and everything is energy in various forms. We’re neither floating down nor observing the river. We are a fragment of it, and we’re right where we should be. Or as Walt put it,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death, And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it, And ceas'd the moment life appear'd.

All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses, And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

As I type these final words, there are two hen turkeys in the yard with a scrum of tiny fuzzy chicks restless as popcorn around their feet. They’re heading for the uncut lawn, feeding on the world we’ve made and unmade.

And for Walt and the turkeys, and much more, there is another human response as vital as awe: gratitude. And from gratitude, the path forward is clear. If there is life here on Earth we cherish, it’s on us to preserve it.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Bryan Pfeiffer at Chasing Nature, a great tale and even better essay describing Bryan’s 20-year quest to find a tiny, rare, beautiful, and elusive butterfly, the Bog Elfin, in Vermont. The writing is particularly smart and lovely as it explores the question of the butterfly’s importance in the scheme of things:

In our safeguarding little brown butterflies, like protecting speech, we show reverence not only for the popular and charismatic and profitable, but for the obscure and the vulnerable as well. Vermont is now a better place for having Bog Elfins — up there in the spruce where they belong, overseeing the orchids and songbirds and blackflies, even aging biologists like me. Protecting little brown butterflies is good for the integrity of nature — as it is for integrity of humans.

From E&E News, “Post-Sackett, Chaos Erupts for Wetlands Oversight,” a follow-up on the Supreme Court’s ridiculous and catastrophic ruling on wetlands. No one knows how this will all shake out, but it will be ugly. Developers and industries are licking their chops while conservationists, lawyers, and state lawmakers figure out their next steps. Estimates of the catastrophic amount of wetland habitat on the chopping block include numbers like these: 81% of the Everglades, 59% of stream mileage in Virginia, and 86% of wetlands in Indiana Dunes National Park.

From the Guardian, a troubling update on the fate of global ocean circulation I wrote about several weeks ago in The Undercurrent. The same researchers behind the landmark study showing that excess glacial melting in Antarctic waters would significantly slow global circulation are now saying that most of the slowdown predicted for 2050 has already occurred: “We’re seeing changes have already happened in the ocean that were not projected to happen until a few decades from now.”

From Grist, a primer on whether it’s better to plan on capturing carbon with trees or machines.

From Mother Jones, a concentrated U.S. effort to persuade Turkmenistan to deal with its “colossal” and “mind-boggling” methane leaks.

From the Times, insurance companies are increasingly refusing to sell coverage in areas hardest hit by climate-related disasters. State Farm, for example, is no longer selling new policies to homeowners anywhere in California. These companies, and the giant re-insurers that cover them, have long recognized the threat that the climate crisis poses to business. Now they’re cutting their losses and leaving people and governments to figure out their options.

From Yale e360, the plastics and fossil fuel industries are working hard to saddle civilization with another terrible idea: “advanced recycling” by pyrolysis, the heating of plastic waste to turn it back into fossil fuels. Claimed by industry to be a solution to plastic waste, it is actually a blueprint for keeping society locked into fossil fuel use. “Advanced recycling” isn’t really recycling at all, because it doesn’t reduce the need for new fossil fuels.

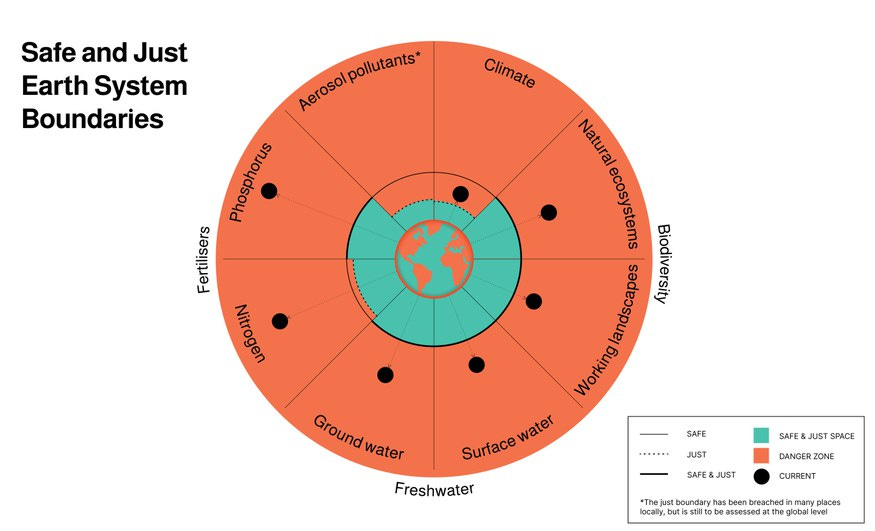

From the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, a new graphic for understanding how in the Anthropocene we’ve exceeded boundaries for both planetary health and human well-being. This comes from the same folks who created the Planetary Boundaries metrics that I’ve written about extensively. The difference here is the included measures for “safe” and “just” boundaries in human terms. I will certainly be writing about this someday. As before, the graphic requires some translation.

Lovely, lovely essay. What a great topic! You're very fortunate to have a mind like that, experiences, like you've had, and reactions to beauty, immensity, splendor and quiet grandeur like you've had. Plus the writing skills to convey inkling of it to your readers. Contrast your stance toward the world with that expressed by the phrase, "Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom." They are polar opposites.

I once sat on a hillside in an Asian country, looking at two white butterflies chasing each other in a tight spiral up into the blue sky and a voice came to me, "Beauty is the path to the highest." or words to that meaning.

I regret not getting the feeling of awe too much anymore, it's a Gift, when it does come. I dwell in its younger sibling Wonder, still though. And their cousin, Gratitude. Finitude in Time and Space is not a thing to lament.. it's a blessing.

I love this quote:

"When I looked down over the rotting mountains of Sinkiang to the distant snowy hills I sensed a vague but familiar affinity to something great and enormously calm. I could never track it down or identity it inside me, and this time it remained shapeless as well. I felt this affinity intensely, though I couldn't see more than reddish distant mountains, motionless glaciers and clouds silently coming up the valleys.”

-alpinist Voytek Kurtyka