An Orphan of Silence

1/19/23 – Charles Simic, poetry, eyes open and closed, and some memoir

Hello everyone:

I had planned this week to take a break from essay-writing and provide you with a practical explainer for the array of new and substantial energy-efficiency incentives provided by the Inflation Reduction Act. But something else came up, and the explainer will have to wait.

For those of you new to the Field Guide, and there are a lot of you in recent days, please know that this week’s writing is a major departure from my usual discussion of our rapidly-changing planet. If you haven’t already, please dig into my recent pieces for a good sample.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I wrote last week, in An Informed Reverence, that I had enough poetry in me to assess the meeting ground between the physical and the metaphysical. The statement seems like an intellectual confection, I know, but I meant it literally.

By “physical” I mean the known and tangible world, and by “metaphysical” (defined roughly as “beyond the physical”) I mean the abstract concepts conjured up by the human mind to pretend an understanding of life’s mysteries: gods, God, love, being, existence, and reality, to name a few. I’ve spent my life wandering through landscapes and ideas, looking closely and understanding little, and trying to weave things together with phrases crafted finely enough to convert silence into sense.

I began my writing life as a poet and had no intention then of doing any writerly thing other than scribbling small strange poems into my notebooks. I sought and earned a Masters in poetry because I needed to. Poetry seemed both sea and ship to me then – a way of navigating this wonderful, strange, deluded, self-destructive civilization chewing its way through the green world – and I sought out the opportunity to spend a couple years anchoring poetry into my life.

Why am I writing about this? Because Charlie Simic died last week, and the world is a lesser place without him. Charlie was one of the great poets of the last half century, a voice for souls lost to the pages of history, a street-smart philosopher of misery and joy, a child of war, a lover of blues and good food, a purveyor of surreal and darkly comic images made “to annoy God, and make the Devil laugh,” and generally a brilliant, funny, and down-to-earth sweet guy. He was fluent in several languages and translated poems from French, Serbian, Croatian, Macedonian, and Slovenian. He was the U.S. Poet Laureate. Charlie won a Pulitzer and a MacArthur genius grant and too many other honors to mention here.

He was also my teacher. For my two years at the University of New Hampshire, he and Mekeel McBride (another brilliant, wonderful, mystery-filled human being) provided space for me to grow as I wrote my small strange poems and went deeper into the literary tradition I had joined.

I’ve somehow spent my life in the orbits of very intelligent people, world-class scientists, etc., and am fortunate enough to be married to the most empathetic person I know (empathy, in the end, being the highest form of intelligence), but I’ve never felt the presence of genius like I did around Charlie. I don’t mean to put him on a pedestal – he had his faults, and was the first to acknowledge his ordinariness – but the articulation and humor and depth of historical and philosophical awareness that emanated from him whether in class or in his living room was intense. Genius, I think, isn’t mere intelligence; it’s an integrity and force of spirit expressed through a clarity of mind.

Charlie’s method of teaching poetry workshops consisted mostly of assessing the success of each line and image and their usefulness to the poem. I’d chosen Charlie and UNH over the University of Iowa, which was then the center of the American poetry world, where as I understood it each workshopped poem was elevated and examined in 3D for its value system and voice. With Charlie, we heard a lot of “Good” and “Not good” in his thick Yugoslav accent as his pencil carved through the poem like a warm knife through butter. It was a simple process that worked for me: a poem is a crafted object that must be drawn and redrawn until it fails or finds its true form.

Charlie took great joy in the tension between the seriousness of making poems and the absurdity of the human condition. Tragedy, foolishness, cruelty, love, honor, happiness, truth, and lies were all threads in the tapestry of life that our poems were somehow trying to convey. The work was both necessary and impossible, and that was funny to him. And he made it funny to us.

There were great stories of Dadaists and other eccentric poets. There were one-liners borrowed from comedians and blues singers, and expressions of wonder for a poet like Elizabeth Bishop, who “never wrote a bad poem.” And there was no shortage of poetry wisdom to be handed down.

One of the nuggets that’s stuck with me is the distinction between the two types of written images: those made with eyes open and those made with eyes closed. An eyes-open image is a description of the visible; an eyes-closed image is imagined into being.

I think of this distinction often when mapping out in these pages the path we took to reach the Anthropocene. The folks with eyes open – Indigenous peoples, ecologists, naturalists, children, activists, and anyone else not lost in the supermarket – have always seen and felt the consequences of the destructive fantasies that required the enslavement of the natural world to our desires. With your eyes open, you can hear better the bizarre irrationality of “constant growth” and “Are we alone?”

In this distinction, you can also hear an echo of physical vs. metaphysical. The meeting ground between them is where we all live, awake to the world but dreaming of alternatives. Charlie played frequently with this dynamic between the visible and the imagined. For those of you interested in how this plays out in a poem, you can see it in this selection of stanzas from his poem “Trees at Night,” in which the speaker is listening in the darkness to the wind in the branches:

Putting out the light To hear them better. The sound of those Who sleep without dreams. At times also like the tap Of a moth On a windowscreen. A flurry of thoughts. Sediments On the bottom of night’s ink, Seething, subsiding. Branches bending To the boundaries Of the inaudible. A prolonged hush That reminds me To lock the doors. Clarity. The mast of my spine, for instance, To which death attaches A fluttering handkerchief. And the wind makes A big deal of it.

For a straight eyes-open example, here are a couple lines from a recent poem by Nomi Stone, “Anthropocene:”

Larkin says what will survive of us is love, but the scientists say that the end of the decay-chain is lead and uranium and after that, plastics.

On the page, Charlie was a poet of brevity surrounded by silence. “Of all the things ever said about poetry,” he once said in a brief but excellent Granta interview, “the axiom that less is more has made the biggest and the most lasting impression on me.” Less is more: Charlie knew that words have to compete with silence, where most wisdom lies, and he knew that a terse and mysterious clarity could draw and keep a reader because it hinted at something much larger.

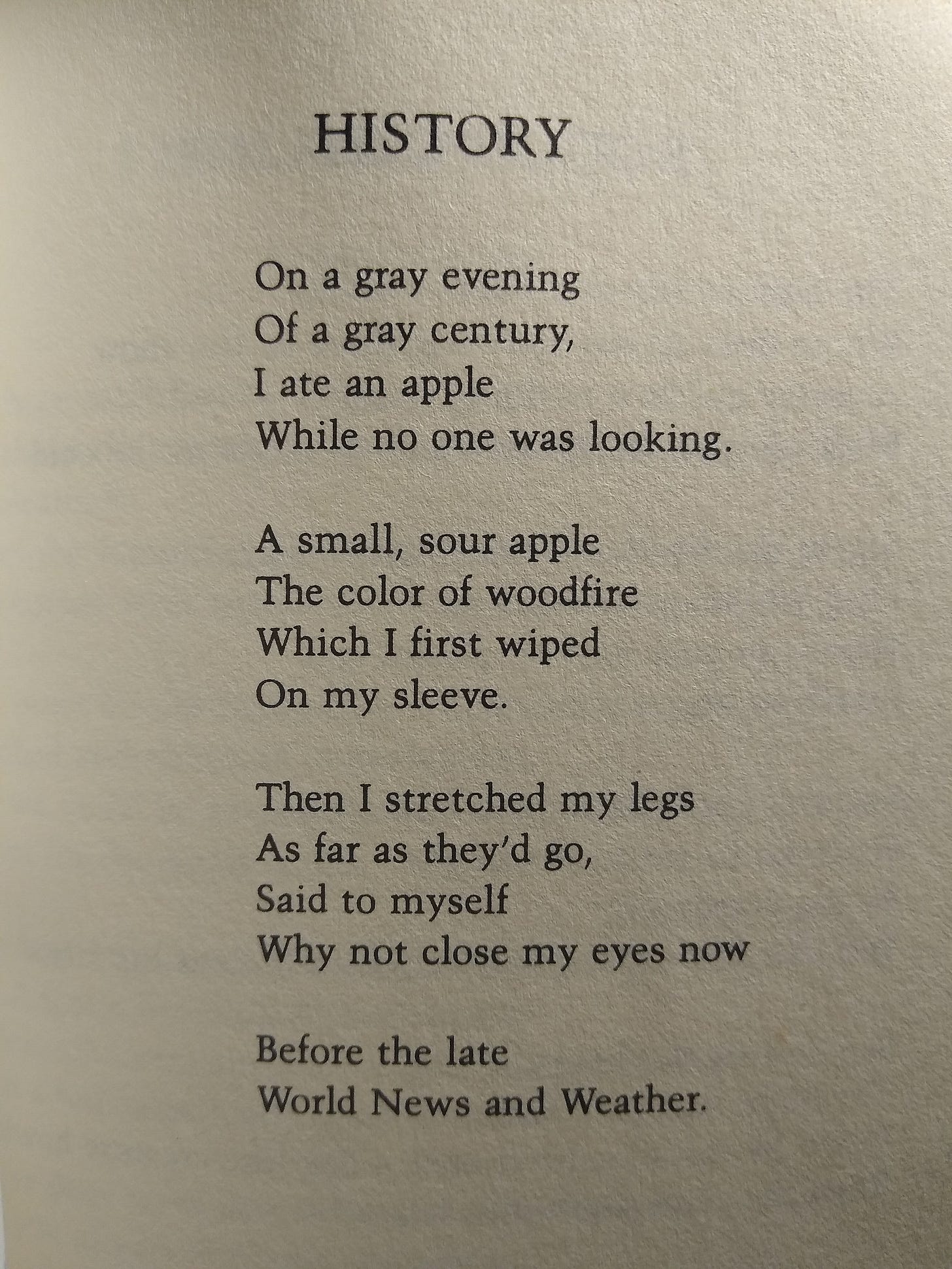

As a result, his obituaries seem to feel obligated to describe his poems as deceptively simple. So much is happening below the surface of a Simic poem, like here in “History:”

You can hear the silence around this narrator – a refugee and his stolen apple exhausted on the side of the road? – as he unapologetically notes his theft in an Eden-less world full of smoke and moral gray areas. Charlie knew that history is a broom that sweeps away both truth and individual truths.

He grew up in war-torn Sarajevo: “I had a small, nonspeaking part / in a bloody epic,” he wrote in “Cameo Appearance.” Who needs the World News if you’re living it? Just ask the Ukrainians and Ethiopians and others fleeing their homes into gray silences.

Charlie’s thoughts on the value of silence and solitude (from a 1972 interview with Crazy Horse magazine, reprinted in his book The Uncertain Certainty) are worth quoting at length, because at heart what he’s saying is about the soul in the wilderness, which is where we all are:

Silence, solitude, what is more essential to the human condition? “Maternal silence” is what I like to call it. Life before the coming of language. That place where we begin to hear the voice of the inanimate. Poetry is an orphan of silence. The words never quite equal the experience behind them. We are always at the beginning, eternal apprentices, thrown back again and again into that condition. There is a complexity which demands its equivalent in words. Of course, it is impossible to do it justice. I say Yes to the impossible – therefore poetry.

This is what we all share, a condition where both the content and the form are one. The deeper a voice calls from that maternal silence the wider is its echo. Occasionally people think of silence as something negative, passive. For me silence is the spiritual energy. Of course, the paradox is that neither is there such a thing as silence nor is one ever alone.

I wandered off after grad school to Antarctica, a continent of such astonishing silence that it haunts me still. I felt then, and know now, that I hadn’t emerged from UNH with any really good poems or, worse, a clear voice or purpose. I could make small strange poems, I could channel the mystical energy that feeds the act of poetry, and I could make lines and images sing, but I rarely wrote a poem that felt clear and true. Such failure is the hazard of trying to make art, of course, and it’s also the stimulus. It’s the “impossible” that Charlie mentions above. But my writing faced a bigger challenge.

I’ve often said since that Antarctica erased my poetry, because the silence and icy landscape out-competed the white space of the page. It’s not a place for artifice. But the truth is a bit more complicated. I’d succeeded in anchoring poetry in my life, but after a season on the ice poetry was no longer my sea and ship.

Instead, I obsessed for years on how to write the Antarctic landscape with language at the margin between poetry and prose, often in small prose fragments. Here are two samples:

How to be a witness to an ice age: stand back, scratch your insulated head, fill a notebook with incomplete thoughts. Sketch the gap you hear.

***

Antarctica confronts us with the inherent threat of a landscape more resilient than life. To be made of flesh, and to carry a consciousness that knows the futility of flesh against this cold, is to be living in the moment of a dream in which beauty and death appear as a single seed. The depth of one's fear determines which of these, beauty or death, we believe contains the other.

Eventually, I figured out how to write decent straightforward prose and use it to write Antarctic essays, though I always had my poetic license in my back pocket, just in case. Then I wrote my first book, a narrative history of the human experience of the Antarctic called Hoosh: Roast Penguin, Scurvy Day, and Other Stories of Antarctic Cuisine. I love the book, but Hoosh certainly represents the furthest departure from my poem-scribbling days. I sometime feel a bit guilty for moving on from poetry, as if I’ve neglected Charlie and Mekeel’s vision of my future, but my journey has been an honest one. I still write poems, though rarely and slowly.

Now I’m here, crafting my thoughts about the transformed Earth in this field guide to the Anthropocene. I’m beholden largely to an eyes-open aesthetic as I weave together essays about nature and human nature, about problems and solutions. But I’m reminded that Berthold Brecht, in exile from Germany during the build-up to WWII, wrote this dialogue into a poem:

In the dark times

will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing.

About the dark times.

Less is more. These lines contain so much. Is this dark humor, fatalism, or optimism? If the singing is about the darkness, then has the darkness won? Difficult times restrict creativity and obligate artists to respond. But life during struggle is more than just the struggle. Imagination can thrive, even if it has obligations.

Lord knows that a hell of a lot more people should be paying attention and taking action as the planet burns and life dwindles, but essays about a planet-chewing civilization and its consequences can sing at least a few sentences now and then. Thinking about Charlie and poetry this week is a good reminder that I should remember to close my eyes a bit more often when I’m writing, and sing more often, like in this paragraph from my recent piece, We Are Not Alone:

The Sun’s energy is contained in samara and lichen, woodpecker and hare, fern and mussel and thrip. Everything is alive, always, even in death. Life is defined not by form or heat but by flow and relationship. Everything is connected, and energy can neither be created nor destroyed. It seems to me that for naturalists, as for mystics, time and space should seem less units of measure than threads in the fabric.

Charlie was a devoted city boy rather than a naturalist, though he spent the last forty years living in the woods next to a New Hampshire lake. For him, nature was best symbolized by a fresh tomato salad with some onion, basil, and olive oil. He also liked to joke that it was hard to love nature because he couldn’t help thinking that nature was what was killing him. But he had the soul of a wine-drinking, tree-contemplating mystic, a poet who found his true form in the universe as he sent out lines like fingers trying to touch whatever it is that forms the silence that contains us all.

You can read quite a few of Charlie’s poems online here. (Scroll down past the bio to find them.)

Of the obituaries I’ve read so far, I liked Scott Simon’s brief and poignant remembrance over at NPR, and a longer, denser appreciation of his work at the New Yorker. The Times has an excellent obit too, as always.

Finally, then, I’ll say what all remembrances and obituaries are trying to say: I miss him.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the Times, a good-news update on the slow healing of the planet’s ozone layer. China cracked down on rogue industrial emissions of chlorofluorocarbons, and the best estimate now is that the ozone layer will reach pre-1980 levels by 2040.

From NPR, a reporter’s difficult journey to shop plastic-free for a week’s worth of food. This story matters because it demonstrates the extent to which the single-use plastics nightmare (for both climate and biodiversity) is built into our lives.

Check out Aussie Ark, a major Australian wildlife and rewilding organization doing excellent work. Take a look at the wonderful species they protect, and donate if you can.

What’s the best way to restore forests, especially tropical forests? Start by protecting the wildlife, which can do much of the tree-planting work for us. Find out more in this article from the Yale School of the Environment.

From The Overpopulation Project, “The Great Multiplier,” an interesting analysis of whether consumption or population is the greater contributor to global climate change.

From the Guardian, ocean temperatures in 2022 were the highest ever recorded, and are likely “heating faster than at any time in the last two thousand years.” As one scientist noted, “If you want to measure global warming, you want to measure where the warming goes, and over 90% goes into the oceans.”

this was gorgeous, well-received and much needed. thank you so much for thinking of me. all good things. +1

beautiful and moving tribute