Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Heather and I were stopped short a few days ago, on a long walk through one of our favorite local conservation preserves. The trail was still icy and snowy in places, but where the Sun could reach it had melted or sublimated the snow and revealed the living city of soil and low plants that has been hidden from us for months.

The revitalized smell of the earth has been delicious. The oils and dust of life, freed by the melting, float back into our senses. It reminds me of my once annual return from the largely lifeless surface of Antarctica to the green haven of New Zealand. Back then, I could smell the much-missed Earth long before landing, and to my starved senses even the fuel-tainted airport tarmac was rich with the scent of the trees and fields that surrounded it.

It wasn’t the smell of life that stopped Heather and me, though, since that joy traveled with us. And, to be clear, we’d made other stops: to look at tree buds preparing to burst, at skeletal beech leaves that had been whispering all winter, at a pileated woodpecker chiseling into a standing white pine, at the richest trove of partridgeberry we know of, and more. But what really jumped out at us was a verdant community of mosses and lichens blanketing a rotting spruce log, a deep rich island of greens emerging from the receding tide of snow.

The picture above is a poor attempt to capture its vibrancy. My phone camera didn’t know what to do with the contrast between the snow and the log. Here’s a close-up that offers the spirit of the moment (if not the depth of color or proper focus):

I’ll let the moss- and lichen-lovers among you sort out the species. For me, this beautiful tapestry of small green forms was my momentary New Zealand, my arrival into Spring.

Spring is always the joy of emergence - or reemergence, really - as the promise of the season holds true. The rust falls briefly from the clichés (new beginnings, a page turned, etc.) and we turn toward whatever the light will bring.

Another benefit of the walk was the relief from the news. As I expected immediately after the U.S. election, much of what we’re experiencing is a deliberate and radical increase in suffering. You and I can cite the varieties of intentional suffering already in progress, from the cruel and senseless cuts in life-saving global aid to the fatal delay in climate action, and from the demonizing of immigrants and refugees to the gutting of the EPA. The headlines fall like unnumbered snowflakes and hope seems to melt away. A walk in the scented forest is always good for the soul, but we need it now more than ever.

I don’t mean to turn the beautiful mossy log that opens this essay into a Trojan horse for the terrors of the Anthropocene. (Not that I’m averse to such behavior, as my long-time readers know.) But after the walk, returning back into the built world and its hollow rooms, I was struck by the dislocation I felt between the emergence of the moss and the constant churn of the political/social mess. Both are in motion, alive amid the flow. Both are arriving and emerging.

In this time of troubles and its acceleration of the life-on-Earth calamity we call the biodiversity and climate crises, it’s worth spending a few moments thinking about how we relate to the idea of change. Clearly, some changes buoy us while others swamp the boat.

What I’m after here is some kind of answer to these questions about our relationship with emergence: Do I live on the Earth amid its patterns of slow, sudden, and seasonal change, or do I occupy a data point in the cultural flood of information? How do I portion out my loyalties to both the river and the news? How deep in either torrent of change should I stand?

I’ll start by noting that even Spring has its discontents. Here in the northeast U.S., at least, among those of us who love winter and who dread the now-constant warm-season menace of tick-borne diseases, there’s some reluctance to lose the snow cover amid the transition to light and life.

But on we go.

The seasons emerge as the planet spins and orbits in a larger dance that is, as yet, unperturbed by human interference. Everything else, though, seems up for grabs. The so-called Anthropocene has emerged out of the so-called Holocene as our actions create biotic poverty from ecological complexity.

It’s hard for me not to see it everywhere.

The climate grows stranger because we’ve cut down a third of Earth’s forests and pumped out a supervolcanic quantity of greenhouse gases. The oceans are 30% more acidic than they were two centuries ago. We’ve altered about 97% of Earth’s land surface (not including Antarctica) for our own purposes. In just my lifetime, human population has increased 122% while the populations of nearly 5500 long-studied species (mammal, bird, fish, reptile, and amphibian) have fallen on average by 73%.

And then there’s Anthropocene politics. Among the warnings of the indispensable “Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future” (i.e. the “Ghastly” study, as I’ve called it since I first cited it here in the Field Guide four years ago) is that good governance will be necessary to meet the crises head-on, but good governance - already hard to find - can grow scarce amid such crises. Specifically, the study notes that

the continued rise of extreme ideologies… limits the capacity of making prudent, long-term decisions, thus potentially accelerating a vicious cycle of global ecological deterioration and its penalties.

So yes, of course, there is a steady and intensifying drumbeat of news about our impacts on the living world, if you have ears to hear it.

But again, rather than read you the antibiotic litany of the current and future right-wing oligarchic Trump agenda, I want to muse on our relationship with all that emerges. There is so much more, including so much that is good and beautiful, to pay attention to.

We forget that the daily frenzy of “news” is bizarre in the context of our species’ history. Our consciousness is a scaffolding of stories, real and imagined, but it’s better suited to campfire conversation than the narrative inferno of a global internet. We live local lives (neighborhood, shantytown, village) “informed” by a flood of national and international stories we can’t fully process.

Every week I offer up stories of a world in flux. This week, for example, I have some good-news tales of rewilding happening on New Zealand islands, Chinese farmland, and former golf courses in the U.S.. If inclined to read them, you might duly nod and pass that information on to someone who might be happy to hear it. But who are we, really, in relation to these stories? Is it as intimate as gossip, or as useful as listening to birdsong explain the forest to us? Or is it noise? Who are we as we become both active nodes and monetized data points in the digital civilization we explore from our chairs?

I’ve read that “Let no new thing arise” was (is?) a traditional Spanish or Catalan expression of farewell. Meant as a blessing, it’s an assumption of stability that now seems as arcane and irrelevant as a stone arrowhead. Change is destabilizing, and for most of our history cultures haven’t wanted to be destabilized. Now, new normals are the new normal. We’re always reacting to sea-changes in the life we thought we were living.

Information is impact. They travel together up the steep graphs of the Anthropocene. While there is a stark contrast between how we think and what we’ve done, there is a deep synergy between what we know and what we’ve harmed. Put another way, a million years of human evolution has equipped us to reimagine the planet for our own purposes, but not (so far) to set limits on those changes.

But on we go.

And emergence is so much more than the brief noise of human civilization, and more than just the root of “emergency”. All things emerge: trouble, death, loss, and grief sprout alongside peace, life, discovery, and joy. Time is a tide that brings and removes all things, revealing eventually that there are no things, only tide. All that exists emerges from all that no longer exists, and vice versa.

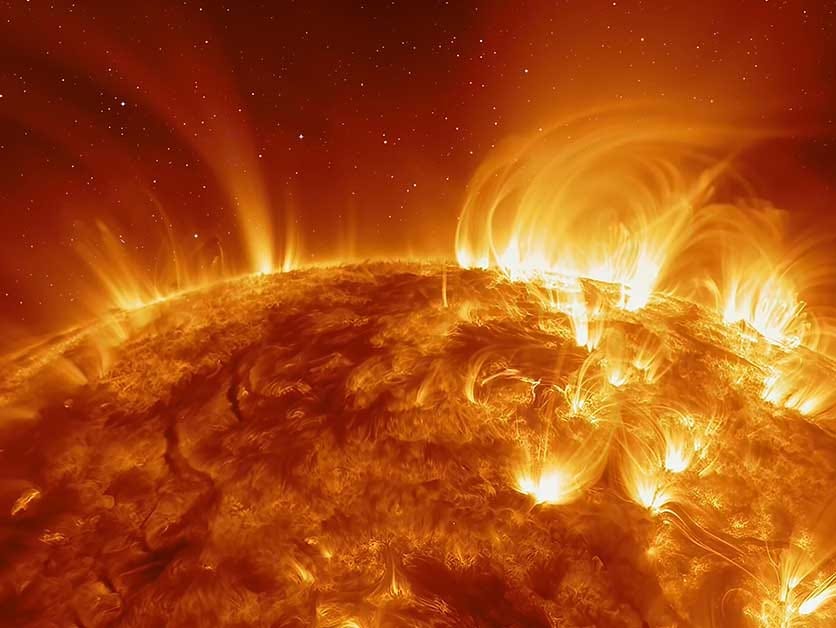

The Sun burns us even at this distance, and destroys anything that draws near, but is the one and only life-giver, the god among gods, amid the major miracle that is this minor solar system. Likewise, the Sun-fed moss and lichen that sparked this essay are busy decomposing the fallen spruce. Life and death are locked in their dance, as Chloe Hope explains so beautifully in “Mycelium.” In their embrace, death “clears a path for the emerging”:

Life knows well when she is no longer the most appropriate keeper of a soul, when it is time to surrender yet another of her charges to the wisdom of her companion, lover and ally… Death. He who clears a path for the emerging. He who rewards the tenured with their return to the everything. He whose sacred shadows render his love light. Life eventually lays every being she has ever known at his feet; such is the depth of her trust in him.

Even on the human plane - which is narrative all the way down - progress and suffering grow from each other’s ashes. Ignorance and knowledge emerge side-by-side, as every scientific or metaphysical inquiry into the nature of nature reveal new realms with unnamed and unopened doors.

Amid all of our information and chatter, science is building a library too large for any of us to read. In it, we are revealing the languages of life - whether quantum mathematics or whale-speak - and revealing how much we’ve been missing. Here’s Rebecca Hooper of

, reflecting on her selective mutism as a child, using the croaks of ravens as her path into life’s mystery:The language of ravens is something we humans do not have a good grasp of. The language of most nonhumans, in fact. Undiscovered oceans reside all around us – they ripple in the larynx of the fox, spiral in the syrinx of the sparrow, churn over the skin of the cuttlefish, crash through the feet of the elephant, torrent on the tongue of the raven.

We should perhaps confess that the chaos of emergence in this era would be easy to manage if it were all good news. Good news, no matter how rapid or strange, is resolved news. Everything else is unresolved, unmapped, uneasy, unpleasant, unnerving, or uncontrolled. Humans are flock- or herd-oriented, and en masse we startle easily.

So the stress we feel as everything shifts beneath our feet (and above our heads) isn’t due to the flood of information as much as it is to what’s contained in the flood. We’re fully equipped to take joy in the change of seasons, the beauty of moss emerging from snow, or a lunar eclipse over the migration of grassland sparrows. We’re less equipped to feel that joy in the complicated context of the Anthropocene.

But the Anthropocene means that all of these changes - slow and sudden, Spring-like and civilizational, sweet and cynical - are connected. When a new oligarchic, methane-spewing administration slouches into the White House, that’s bad news for moss and migrants. Hurricane season and a gutted EPA are both bad for grassland sparrows. But it cuts both ways.

New forms of political resistance are taking shape even as cheap solar energy begins to make fossil fuels obsolete. Everywhere, good news emerges in the form of folks working to rewild islands, undermine ideologies, improve climate chemistry, protect the oceans, reverse our civilizational footprint, offer family planning services wherever they’re wanted, and otherwise treat the Earth like home.

We must somehow pay attention to all of it. Not all the news, of course, and not even all of nature. But we occupy the real world and must protect it as we’d protect our own home. At the same time, we are trapped in this world made for us out of the bulldozed Earth, and must help remake with empathy both the bulldozer and the Earth.

As for figuring out how to portion out your loyalties between the river of life and the flood of news, I don’t have any answer that you don’t already have. Stay sane but stay focused. Go outside and remain as long as you can. Love the world as it should be, and act accordingly. Emergence is everywhere, and in us too.

I’d like to end by offering this blessing - Let no new thing arise - but we both know better. And so on we go.

But I can leave you with a final note on Spring, this season that is not merely a time of emergence but more importantly a celebration of the persistence of life. Mary Oliver reminds us that we need only be as durable as moles as we face the varieties of winter that befall us. From “Moles”:

Field after field you can see the traceries of their long lonely walks, then the rains blur even this frail hint of them -- so excitable, so plush, so willing to continue generation after generation accomplishing nothing but their brief physical lives as they live and die, pushing and shoving with their stubborn muzzles against the whole earth, finding it delicious.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

In honor of Spring, I’ll keep the news upbeat this week:

I’ll start, appropriately enough, by highlighting Emergence magazine. Emergence offers high-quality interactive essays, documentary films, and interviews with some of today’s leading ecological writers and thinkers. Recent interviews include Robin Wall Kimmerer, Zoë Schlanger, and Amitav Ghosh. Here’s an editors’ note to give you a sense of what the magazine intends to offer:

It has always been a radical act to share stories during dark times. They are regenerative spaces of creation and renewal. As we experience a loss of sacred connection to the earth, we share stories that explore the timeless connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality.

As always, I recommend anyone interested in the most comprehensive round-up of biodiversity news available to subscribe to

’s . Every issue has concise one-paragraph descriptions of a few big stories plus several lists (with links) of interesting stories, scientific papers, and job information for journalists covering biodiversity issues. It’s a great resource, and well worth your support.Two upbeat and self-explanatory stories from Reasons to be Cheerful, “How Heat Pumps Became America’s Hottest Home Energy System,” and “Former Golf Courses are Going Wild.”

From

, a podcast interview about a very large, high-concept sustainable community being built in the heart of conservative oil country in Edmonton, Canada.From Mongabay, the wonderful ambitions of New Zealand to scale up its multi-generational island rewilding work to three islands that are much, much larger than any they’ve cleared of nonnative predators before. I wrote in depth about this work in “Cruel to Be Kind.”

From the Guardian, the astonishing re-greening of the massive Loess plateau in China, which at the end of the 20th century was one of the most degraded and denuded agricultural areas on Earth. They’ve learned to plant forests rather than just trees, and they’ve had to adjust their ambitions as the world warms, but some of the old ecology is returning.

You write, "Do I live on the Earth amid its patterns of slow, sudden, and seasonal change, or do I occupy a data point in the cultural flood of information? How do I portion out my loyalties to both the river and the news? How deep in either torrent of change should I stand?"

I dare not preach to you or anyone else, but for myself the answer to these questions is unitary: I myself am the torrent and continual emergence. Whether autocracies rise or fall, whether the planet heats or cools, whether the universe itself expands or collapses- in the middle of the raging fires of change, if I but stay true to compassion and loving kindness, it all matters not.

There is a still center in the midst of all tumult. It abides eternally I feel.

Exquisite piece of writing about the spring of 2025!