Hello everyone:

I only recently remembered that this week marks four years of the Field Guide. I’ve published more than 200 essays (minus some repeats and weeks off) since Earth Day, 2021, all in a quest to usefully describe the strange world we’re making from the astonishing planet we’re unmaking.

I’ve tried to strike a balance between articulating the disrupted world for you and reminding you of how beautiful and wonderful that world is. Thank you all for joining me in this effort. I’m grateful especially to my paid and founding subscribers who make this work possible. I cannot say enough how wonderful it is that people support the work that I’m compelled to do.

Earth Day arrives on Tuesday the 22nd, between this essay and the next. If there’s a social activity (e.g. tree-planting) or act of resistance/resilience (protesting the simultaneous destruction of U.S. governance and environmental protections) that will help you stay connected to the fate of the planet, then please join in. Otherwise, if you can, get out into the beautiful world and pay attention to it. As Mary Oliver says in one of her Upstream essays, “Attention is the beginning of devotion,” and the living Earth needs us all on, or beyond, that starting line.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

The Urge to Live

Spring has seemed reluctant to arrive here in Maine. I can’t entirely blame the local climate for holding on to snowstorms and Canadian winds. On the raw days of wintry spring, it feels to me like the last gasps of an ice age struggling against our apparent determination to bring back the Eocene. Summers have been filling up with far too much southern heat. There’s optimism in trying to store up the chilliness against what’s coming.

But really, this is normal spring variation in Maine. Weather and temperature change by the moment, and the seasons shift in tides beyond our ken. I’m glad for the snow and cold rain, which are only good news for groundwater supply and for the life which is moments away from bursting onto the scene. The urge to live is everywhere, even in the poised silence of a reluctant spring.

The recipe, as always, is simple: Just add water.

I went out for my first bike ride of the season a few weeks ago. It was a short ride meant to remind my body what it was in for as I train insufficiently for a few summer triathlons. The highlight of the ride was hearing my first wood frogs of the season croaking softly in a sunlit swamp. Until a few days ago, though, they’ve been fairly quiet, chilled into silence by the persistent cold nights and occasional snowfalls. Likewise, we’d heard only a few peeps from the spring peepers who follow the wood frogs into the spring chorus.

Then we had our first Big Night on the 15th. Big Nights are the first warm(ish) rainy nights of spring, when many amphibian species come out from their hidden lives to breed in the wet worlds of vernal pools, and humans emerge to help them safely cross the roads. My mother and I walked her road late at night, counting spring peepers, American toads, and green frogs, as well as three species of salamander: spotted, red-backed, and four-toed. We didn’t find many wood frogs, because they’d already made their breeding journeys, cold weather be damned, and were croaking away in full chorus in vernal pool waters as the latecomers plodded across the damp asphalt toward the orgy.

I want to pay proper homage to wood frogs, who I consider a totem animal for winter across northern North America. Their adaptation for winter survival is so simple, yet so alien, that it should be the subject of fables and inspirational metaphors. While other animals flee south to warmer climes, snooze in warm dens, burrow below the frost line or into the mud below a pond, or die to leave their offspring in egg or larval form to carry on alone, wood frogs dig a few inches down into the duff and leaf litter - far too shallow to be protected from winter cold - and freeze solid.

No heartbeat, no breathing, no kidney function, nothing. Ice fills the spaces between cells. Even their eyes are frozen. And yet, they live. And they thrive, in part by being the first amphibian to wake in spring and hop cheerfully toward the nearest breeding pool.

Like a human rediscovering love, wood frogs thaw from the inside out. First the heart starts beating again (we still don’t know how), then the brain reawakens, and then the muscles kick into gear. As one summary put it, “The wood frog is completely undamaged by conditions that would be fatal to nearly all other animals.”

You can watch, and learn more about, this wondrous process in these videos here and here.

The Urge to Enslave

Meanwhile, in the far murkier waters of American fascist politics… The worst kind of parasites are in charge of the political ecosystem. They are sucking the lifeblood out of democratic structures, free speech, scientific inquiry, public decency, environmental protections, international diplomacy and aid, racial equity, gender and sexual freedom, academic independence, global trade, financial markets, and the U.S. Treasury.

They must fuel the rise of their quarter-witted ideology on the pyre of our better angels, because it cannot live on its own.

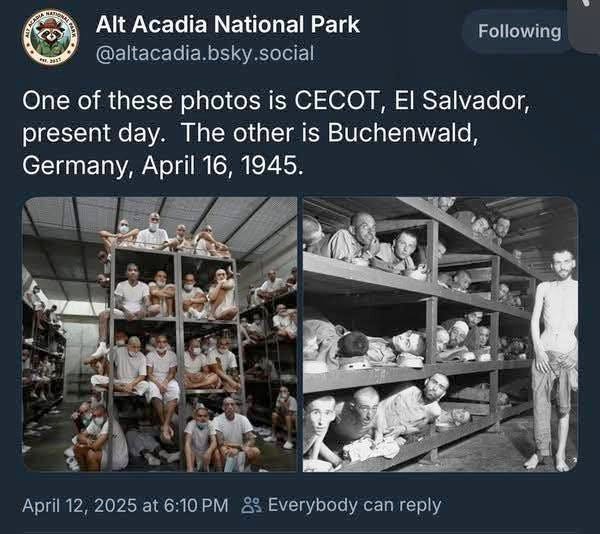

The show of brute, dumb force is live-streamed. We are meant to watch and be afraid. We’re all being crowded into the shallow end of the ideological pool because it’s easier to drown us, or to threaten to drown us. As Indrajit Samarajiva writes in his latest scorching post,

Remember that the point of torture and abuse is communicative. It's not about getting information out of a person, it's about getting information out to the population. It's about instigating fear in general, not investigating anything in particular.

To keep their heads above the toxic stew of cruelty they’re cooking up, they are publicly and staunchly opposed to empathy, the golden foundation for any worthy human culture. Elon Musk recently described empathy as “the fundamental weakness of western civilization” and Vice President J.D. Vance twisted medieval Christian theory (“ordo amoris,” a hierarchy of love that begins at home and moves outward to strangers) to justify the destruction of faithful, modest, tax-paying immigrant communities in the country he claims to lead. This demonizing of poor labor is the logic of enslavers.

These are hearts full of ice, never to wake again, in a winter of their own making.

Modesty and Restraint

Most of life thinks, of course. It does so in ways that sometimes very much resemble our own, and more often in ways we cannot fathom except by mere glimpses of scientific measurement and in leaps of empathetic faith that, right now, seem as endangered as these lives we hold in awe.

What does a wood frog think as her brain - only after the heart first wakes - warms to the primordial wonder of leaves turning to soil, and plants feeding on sunlight? What was her last thought before filling her cells with sugary antifreeze and letting a temporary death convert her to stone? What joy is possible when hopping through spring rain from the cold embrace of death to the wet clasp of sex?

Whatever those thoughts may be, they will likely remain mysteries to us far beyond the arc of what we now call civilization. Why? Not because they are unfathomable, but because they are modest. It’s a safe bet that all life other than Homo sapiens think modest thoughts (though I sometimes doubt the intentions of ants and vines) because they are the elder siblings of the living world. They have evolved to know how to live, while we are still learning. The information that shapes their lives is of community rather than self, of integration rather than separation. Even the parasites that fill the tree of life practice restraint.

Not us, not now. The current dominant culture has ideologies we call hierarchy, supremacy, capitalism. These are empty dreams we fill with other lives, somehow not aware that those lives are extensions of our own.

The wood frog is a model of restraint. She belongs to the world. This may make her thoughts untranslatable to minds that increasingly feed on ideas of complexity.

Pride and Prejudice

“The paradise of the rich,” Victor Hugo wrote long ago, “is built on the hell of the poor.” I would add that both sit atop the death of the living world. Not because humans cannot live modestly on Earth, but because the entire notion of rich and poor is built on the selfish acquisition of “resources” - the lives of the more-than-human world - that belong to themselves.

Economic inequality, as George Monbiot recently articulated in the Guardian, underlies much of our attraction to right-wing ideologues. As the article’s lede put it, “Economic inequality breeds resentment and a desire to get even. That’s what fuels support for even incompetent regimes.” The seductive genius of oligarchic fascist politics is in creating the problem (funneling wealth upward) and then feeding on the resulting anger to remain in power so that it can continue to suck the life out of society.

We are swayed by corrupt, self-serving propaganda to act against our better angels, our own interests, and our own empathetic sense of community. We are taught a false pride to bolster an even worse prejudice.

I’m not a political writer per se, but my foundation as a writer was poetry, and my most important teacher was Charlie Simic, whose poems and essays spoke often to the ideological/utopian horrors of the 20th century. Tens of millions died for the quarter-witted ideas of powerful men - Hitler, Stalin, Mao, etc. - who claimed to be making life better for the masses. I have, ever since, associated the use and power of language with both beauty and horror. In this sense, I suppose, all writing is political. In a society of chattering, intensely social apes, what we say or don’t say about the nature of society (and the nature of nature) defines us.

Defining ideology, meanwhile, isn’t as easy as it seems. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy suggests that the term has become meaningless. Nonetheless, Oxford Languages online tilts political, referring to it as a “system of ideas and ideals, especially one which forms the basis of economic or political theory and policy,” while Merriam-Webster stays vague: “a manner or the content of thinking characteristic of an individual, group, or culture.” The definition that makes the most sense to me comes from Encyclopedia Britannica, which acknowledges that ideology is intended as leverage: “a form of social or political philosophy, or a system of ideas, that aspires both to explain the world and to change it.”

One of the fundamental problems of human cognition is that we often consider irrational ideas to be solid enough to build on and to kill for. When I say “we” here, I mostly mean people in power (or grasping for power) who aspire to explain and change the world for their benefit. They attach intellectual fluff to a flagpole and wield it like a sword, forgetting somehow that ideas are neither as substantial nor as useful as a cloud.

It seems quite likely that the wood frog’s thoughts are more grounded than ours.

All Flourishing is Mutual, All Selfishness is Empty Calories

“All flourishing is mutual,” as Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote in Braiding Sweetgrass, and as she continues to tell us. The closer we look at how the living world actually functions, the more we understand that Indigenous ideas rooted in community (human, biological, spiritual) are more highly evolved (“fitter,” to use Darwin’s term) than what underlies today’s dominant culture.

As biologist Roger Payne noted in a brilliant essay, at the end of a long life dedicated to keeping us connected to the real world, nothing is more important than intact ecologies and a sane culture that seeks to keep them intact:

The way I see it, the most consequential scientific discovery of the past 100 years isn’t E = mc2 or plate tectonics or translating the human genome. These are all quite monumental, to be sure, but there’s one discovery so consequential that unless we respond to it, it may kill us all, graveyard dead. It is this: every species, including humans, depends on a suite of other species to keep the world habitable for it, and each of those species depends in turn on an overlapping but somewhat different suite of species to keep their niche livable for them.

What’s lost in the chasm between the thoughts of a wood frog and those of the cold-hearted ideologue are the ties that bind all we love to all there is. When times get tough, the wood frog’s heart is packed in sugars, while the fascist’s is full of bile. The frog feasts on insects while ideologues eat cake and choke us with empty words.

It’s unclear how much of the current administration’s litany of cruel behaviors are the acts of true believers and how many are just the tools of oligarchic grifters. But the difficulty in discerning the two remind us how corruptible ideology is to begin with.

Sweetness and Resilience

The stark difference between thinking and being can be, in the dominant culture, the difference between life and death for much of the current balance of life on Earth. We invent mirror worlds which neither reflect nor benefit what truly exists. It doesn’t have to be that way, but when our thinking is unmoored from the real world - when ideas become ideology - we are flying a stringless kite.

A stringless kite is not a bird, despite what our imagination conjures up. It can only twist and fall. Nor is a winterized wood frog a thoughtless ice cube. She warms and rises to a world which, like her, always benefits life.

There is sweetness and resilience in the multiple rings of community that defend us against the cold and heartless advances of cruel ideologies. The neighbors and lawyers and protesters standing up for the rights of immigrants and citizens are as vital as the scientists and regulators and artists who strive for a better balance between human interests and the health of the living world.

Finally, perhaps the dense syrupy antifreeze laced throughout a frozen wood frog’s body is a metaphor for a more resilient set of democratic checks and balances. Those much-vaunted guardrails we’ve relied upon here in the U.S. have proven to be more of a polite agreement.

There is an icy wind blowing through American politics (the culmination of a cold front fifty years in the making) working to render all politeness, and all agreements, null and void. Whether we are at the beginning of a catastrophically hard winter, or in the midst of a cold spring from which the deep ecology of resistance will rise to a warming sun, we do not yet know.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Orion, an essay on “imaginal ecology,” which requires us to move beyond our materialist view of nature as an assemblage of things, and to think of the living world instead with “an elevated form of consciousness” that transcends scientific observation and understanding. Our cognitive tools are failing us:

Our current social, political, and climate situation suggests—and I’m being polite here—that we’ve exhausted the information available from the systems we’ve created using our limited language and state of consciousness. But we’ve also fallen short by assuming that we know all there is to know about the natural world in the first place.

From

and , “More than ‘thoughts and prayers,’” a primer on the surprisingly large array of climate-concerned churches and religious organizations, from Episcopalians to evangelicals. Hayhoe links to the climate plans and programs these gatherings of the faithful have committed to, and provides resources for anyone of faith to further organize for the protection of life.From the Guardian, a report on the significant impact pet dogs have on the environment. We are all (or should be) more acquainted with the truly insidious impacts of outdoor cats, but dogs - or really, careless dog owners - are responsible for disturbing or killing wildlife, polluting waterways, and adding to human carbon emissions.

From Grist, the debate over the Forest Service’s insistence on salvage logging the forests decimated by Hurricane Helene.

I’ll finish with three reports from Inside Climate News:

Their exclusive analysis found that a single year of greenhouse gas emissions from tankers carrying LNG (fracked methane gas) from the U.S. more than cancels out the annual emissions reductions achieved through all the electric vehicles currently on U.S. roads.

The Trump administration’s next tactic to undermine protections for endangered species is to try to restrict the definition of “harm” to the species only. In this logic, habitats cannot be harmed, which frees up industries to erase essential landscapes as they wish.

As if in response to all this madness, a new U.N. study describes the necessity of using “deep change theory” to solve the seemingly intractable problems of fossil fuel use, erasure of nature, and unsustainable resource use. “The science is clear on what needs to change,” one of the researchers said. “So if we know what we need to do to change things, why aren’t we doing it?”

A beautiful and important essay. And this: "The stark difference between thinking and being can be, in the dominant culture, the difference between life and death for much of the current balance of life on Earth." Yes! Thank you. (And I always appreciate the additional Anthropocene News.)

That was inspired Jason, thank you!!!