Running AMOC

2/20/25 – Our response to the forecast of a likely collapse of Atlantic Ocean circulation

Hello everyone:

Here’s a big, fun announcement: Heather, my much better half, has started her own Substack. It’s called A Nest of Songs. Heather is a singer-songwriter and a naturalist, among other talents, and in A Nest of Songs will feature two nature-based songs per month, with lyrics, an image, and maybe some additional info. Free subscribers receive one post and song each month, and paid subscribers receive two. You can read her About page for more info, but here’s the fun part:

Recently, I said to my husband: “There are so many f**king love songs. Don’t get me wrong, I love a good love song, but why aren’t there more love songs about nature?!”

Also, this week’s piece is a rewritten and updated version of one I published a year ago, when I had fewer than half of my current subscribers. My apologies to those who read it then, but I’ve suddenly came down with a cold that makes staring at this screen not much fun. I’ve been working on another essay linked to last week’s “We Are Not Alone” piece, and will offer it to you next week.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I often wonder what it would be like to live in a culture whose relationship with the living world was rooted in common sense and empathy. A good description of what I mean comes from the Wingspread Statement on the precautionary principle:

When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause-and-effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. In this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof.

In other words, live responsibly, and always bear in mind that aphorism from medicine: first, do no harm. If a government’s policy or company’s industrial innovation seems like it might be a bad idea, they should prove to everyone that the harm is minimal, or that its usefulness justifies the harm. There is still solid wisdom behind the clichés of better safe than sorry, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and look before you leap.

Why instead do we risk what we risk, especially when what we risk is everything? (The “we” in this discussion is only some of us, I know. I’ve written about it here.) The short answer is culture. Culture is both bedrock and atmosphere for humans, but like all life that flourishes between bedrock and atmosphere, culture can evolve. Therein lies both problem and solution, since culture can either regulate or encourage carelessness.

What if we had a cultural insistence that human and ecological health were higher concerns than economic growth? What if we enforced this belief through policy, and demanded that risk be assessed not by profitability but by ethics informed by science? What if governance and consumer sensibility both insisted that products and activities be proven safe before being allowed into the market?

Instead, we live in a rapidly warming world in which ice and amphibians are disappearing, the oceans are more acidic and less oxygenated, and in which the majority of the 86,000 chemicals registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency “have never received vigorous toxicity testing.” On this latter point, as one expert told the Guardian,

People don’t realize that we actually encourage and even subsidize the production of tens of thousands of chemicals, while imposing essentially no requirements on manufacturers to test their safety. Nor do we ask whether we need the chemical, whether it’s useful, whether there are safer substitutes – or what it’s doing to the environment.

When it comes to climate chaos and the rapid loss of plant and animal life that characterize the Anthropocene, what level of risk should we accept? Think of it this way: If you knew that there was a 0.01% chance your child or grandchild would fall off a cliff at the playground, how cautious would you be? If your nephew wanted to take your kid to the park with cliffs, you’d probably insist that he demonstrate they'll both be safe. Increase the risk to, say, a 10% chance, and the trip probably wouldn’t happen.

Ever since we made the Earth our playground (rather than our sacred home), the odds of catastrophe have increased to 100%. There’s a long and disturbing litany of tragedies that are happening now, and others far worse that we know will occur in a hotter world, even if we don’t know exactly what the chaos and cliffs will look like.

If we knew, for example, that our continued refusal to rein in carbon emissions and end deforestation would trigger a tipping point that would cause your grandchildren (and everyone else’s kids) to live in a world without the ocean currents that stabilize the climate and sustain much of the world’s agriculture, what would you do?

Well, here’s your opportunity to decide. A year ago, a study provided compelling evidence that 1) a warming-related collapse of ocean currents in the Atlantic is quite possible in the world that we’re making, 2) has a particular “abrupt and irreversible” tipping point, and 3) could happen in the next few decades.

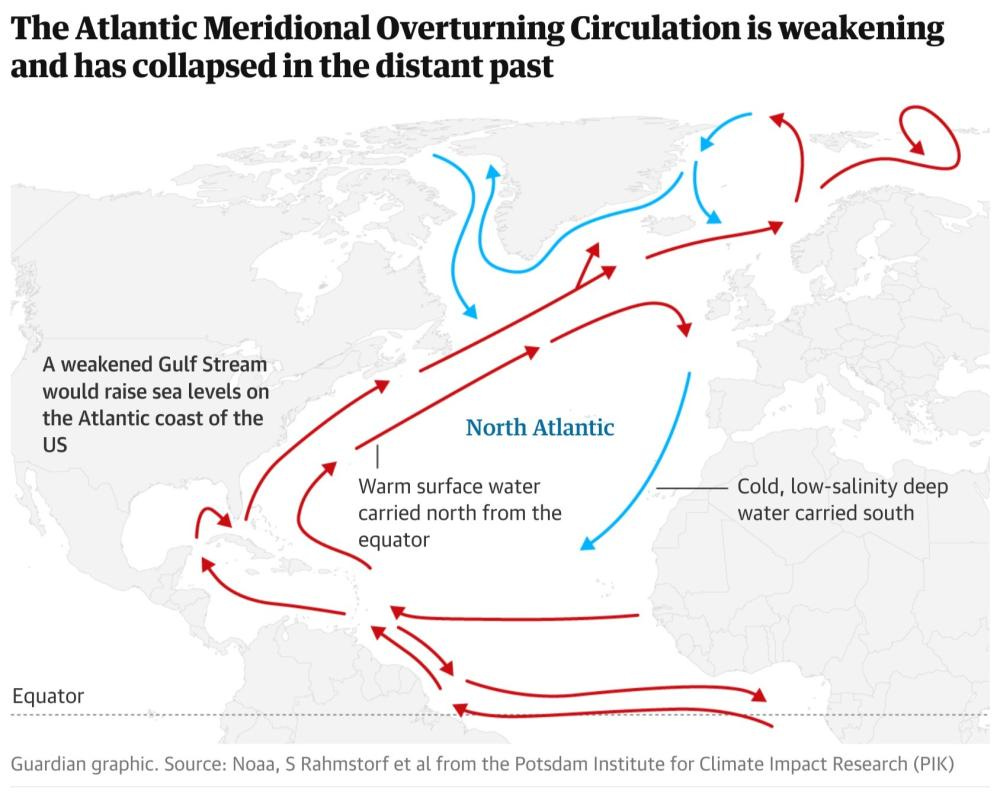

The currents we’re talking about here are known collectively as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC. It’s also known as the Atlantic Conveyor, part of the global “conveyor belt” of currents that move and mix ocean waters throughout the Earth’s seas. (I’ve written about this larger system, particularly its Antarctic context, in a piece called “The Undercurrent.”)

We’ve known from previous studies that the AMOC has slowed by 15% since 1950, that it’s weaker now than it’s been in the last 1,600 years, that it stopped abruptly about 12,000 years ago, and that it has done so often in the distant past. The importance of this study is that for the first time, data suggest that a tipping point can be reached after less than a century of slow decline, and that nothing in the computer models of a warming world is likely to stop that process. Because the AMOC has already been slowing for decades, the authors of the study could not rule out the possibility of the collapse happening quite soon.

The consequences, as I’ll explain in a moment, are stark and global.

The media landscape around this story a year ago was a blip. Even for those of us paying attention, our response so far is to put it on the pile of interesting and scary studies that keep coming out, and to go on with our lives. I include myself here, too.

To be fair, this is ongoing research into a difficult-to-decipher Earth system. There are debates between scientists about the best computer models to use in determining the trend in the data and the likely outcomes. A recent study, for example, disputes the scarily short timeline suggested by last year’s study, but an analysis of both suggests that the new study used an unreliable model. None of the scientists involved, however, dispute the basic theory that the AMOC will slow and collapse in a much warmer world.

It’s probably not a coincidence that the Anthropocene is also an age of excess information. Announcements of existential risk pile up, and announcements of fragile, incremental improvements sit in their shadow. Meanwhile, we live on a busy, narrow road between cliffs and playgrounds.

On the largest scale, as determined by planetary boundaries modeling, our production of hundreds of thousands of “Novel Entities” (including PFAS and PFOAs, pesticides and herbicides, plastics and fertilizers, manmade radioactive materials and antibiotics) now raises the question of how much the Earth can tolerate “before irreversibly shifting into a potentially less habitable state.”

That shift isn’t inevitable, but the fact that we’re wondering how difficult the future we’ve made will be for our descendants tells us how little caution we’ve taken while licensing economic actors to transform the world for their benefit.

There’s a notable level of insanity in fetishizing economic activity because it has an irregular side benefit of helping people, rather than building an economy designed specifically to help people. It’s even nuttier to enlarge that idea to promote endless growth on a finite planet. We forget that the fictions we call economies and corporations are artificial species within the reality we call nature.

With our consent, these entities have turned people into consumers, and turned consumers into products as discardable as what they’ve consumed. What they sell can harm us, without repercussion. In this, the data being scraped from us online resembles the PFAS poisoning our wells and breast milk, the microplastics contaminating our blood and oceans, and the cheap fossil fuels now undermining the stability of planetary systems.

I should correct myself and admit that the precautionary principle is firmly at work in our culture. But not on behalf of humans or the environment. Corporations, the artificial intelligences we’ve been living with for a long time now, have adopted the precautionary principle to protect their own health, at the expense of the living world. Our ability to harm them is tightly regulated.

We live in a culture in which corporate well-being is prioritized, and threats to it are largely neutralized, by policy and laws that force people and the natural world to take on the burden of proof when determining harm. Can most of us live long lives without cancer caused by synthetic chemicals? Can ecosystems and wild animal populations survive the onslaught of profit-driven consumption? Time will tell.

But again, culture can evolve. It can do so quickly, with an election, or slowly and steadily, with a generation of activists and responsive politicians. To establish a bedrock belief, though, is a different task. I’m not sure in a profit-driven society that we’ll ever agree to set precautionary risk assessment as a baseline for economic activity. The most likely time for that kind of transition is in the midst of an emergency so dire than our fear unifies us. That time should be now, but isn’t, because too few of us are willing to identify the emergency from this distance.

Which brings me back, finally, to the AMOC and its importance. To understand how it works, take a look above at the two visualizations from NASA, and read this concise description from the Post:

Scientists often compare the AMOC to a conveyor belt, driven by differences in water density, which transports water, heat and nutrients throughout the Atlantic Ocean.

It starts near the equator, where the surface of the ocean is warmed by the tropical sun. As that water moves northward, some of it evaporates, which increases the salt concentration — and the density — of the water that is left behind. By the time the water nears Greenland, it has also cooled down, which makes it even more dense.

This cold, salty water sinks to the seafloor, pushing the water that was already down there out of its path. That displaced water starts to flow south along the ocean bottom. Once it returns to the tropics, the water is drawn back to the surface through a process called upwelling, and the cycle begins again.

The AMOC slowdown, and likely collapse, are due to a hotter climate increasing precipitation and river runoff in the Arctic, and accelerating the melting of the Greenland ice cap. That increasing flow of cold fresh water, which is less dense, interrupts the Atlantic conveyor’s flow of warm dense water to the north. As that current fails to sink and flow southward, the conveyor weakens and then suddenly stops. The tipping point metaphor here isn’t a light switch we can turn off and then back on. Instead, the Post describes it as someone leaning back in a chair:

As long as they don’t lean too far, they are able to return to their original stable state, with all four legs of the chair on the floor. But if they tilt past a certain threshold – the tipping point – the chair will topple over, and they will be in a new stable state: lying on the floor.

One way to start thinking about the consequences of a collapsed AMOC is to focus on what happens when water, heat, oxygen, carbon, and nutrients stop being transported throughout an entire ocean. The deep Atlantic becomes much less oxygenated, which would prompt a die-off of deepwater species. Without nutrient flow or a vibrant deep ocean, the Atlantic fisheries that feed hundreds of millions of people are upended. As for what happens to plankton and whales, tuna and turtles, seabirds roaming their ancient open ocean paths, migratory eels, and everyone else in the living sea that relies on these currents, we can only imagine.

And that’s just the tip of the melted iceberg. Europe, no longer comforted by the warm tropical water pushed northward, would cool by as much as 3° C (5.4° F) every decade. To understand how chaotic that would be, note how we’re struggling to handle the changes from global temps rising by just 0.2° C per decade, less than a tenth the speed of AMOC-induced change. London would quickly be reminded that it’s on the same frigid latitude as the barrens of southern Labrador. Trying to maintain agricultural norms in the U.K., one expert told Inside Climate News, would be like trying to grow potatoes in northern Norway: “You cannot adapt to this.” Meanwhile, Norway and its neighbors might begin to resemble northern Siberia.

These conditions in Europe would echo the Younger Dryas event, a 1,200 year-long freeze-up that happened about 12,000 years ago. The Younger Dryas turned the U.K., France, Germany and Poland into tundra, and Scandinavia into polar desert.

It occurred because the AMOC collapsed.

But a frozen Europe wouldn’t change the larger climate equation. The world would keep getting hotter, and would get weirder faster. In fact, the southern hemisphere and tropical regions would heat up faster because the AMOC would no longer be shifting some of its heat to the north.

The AMOC is one of the planet’s important climate regulators, controlling wind, temperature, and precipitation patterns around the globe. Losing it, according to one analysis the Post cites, could quickly bring drought to as much as half of the world’s growing areas for corn and wheat, and destabilize the monsoons that bring life to Southeast Asia and West Africa. In the Amazon, the rainy and dry seasons could suddenly reverse.

If you think the future of water and food systems for eight to ten billion people look tenuous under current conditions, or if you worry that biodiversity is suffering from our torquing of the climate, wait until we turn off the AMOC spigot.

The entire world would be affected, with sharp differences between regions and increased chaos between them. Tropical trade winds would shift south, bringing permanent La Niña-like conditions: intensifying monsoons in the South Pacific, China, and India, and worsening heat and drought in parts of North America. Imagine more Australian floods and California droughts.

Sea levels in the north Atlantic region, like along the eastern U.S., would increase by up to a meter, as north-flowing water piles up. Warm coastal waters would keep warming, rather than flowing north to be cooled, which would likely intensify the strength and precipitation of coastal storms. Meanwhile, Arctic sea ice would recover and expand as far southward as Ireland and the U.K., helping to mask global heating even as the tropics and southern hemisphere boil. As the Arctic refreezes, Antarctic sea ice would likely decrease and set the stage for faster glacial loss from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

It's tempting to look for the benefits of an AMOC collapse – more sea ice and reduced methane loss in the Arctic, good glacier skiing in the Alps! – but the truth is that we cannot imagine the scale and speed of the suffering and chaos that would ensue.

What we do know is that we should do everything humanly possible to prevent the possibility of an AMOC collapse. We can’t say with absolute surety that the collapse will happen, nor when it might. But we now have enough evidence to say it’s quite possible, and perhaps in the near future. And this brings me back to the precautionary principle.

Even if there’s only a small risk – 1%, say – of an event precipitating sudden planetary chaos, in which all of our grandchildren and their grandchildren fall off the cliff, the burden of proof should not fall only on the scientists to prove its likelihood. Those creating the harm should take responsibility for the possibility and, if scientific observation suggests that the risk is increasing on our current cultural path, then the burden of proof falls entirely on the industries and governments who created that path. And that’s where we are now.

That last paragraph is a fantasy, of course, when set against the backdrop of how the fossil fuel industry and their pocketed politicians have lied about the known threat of a hotter world these last several decades and, more recently, purchased the White House policy machine for energy and the environment.

One of the many tragedies of Trump’s reelection is that we need better governance now more than ever, because the Anthropocene is all the evidence we need to see what happens when the precautionary principle has been discarded for so long. If global society relied on science, believed in the precautionary principle, and had allegiance to the living world, the long list of climate-related threats that are kin to the AMOC collapse would be an all-hands-on-deck alarm. Yet we still yawn over these science articles, these blips in the news, somehow unaware that our children or grandchildren will be suffering from them in the near future. “We are not,” one scientist told the Post, “taking this seriously enough.”

So, what do we do about the AMOC? We do our best to stop the Greenland ice sheet from melting into the sea. How do we do that? We eliminate CO2 and methane emissions and global deforestation immediately. How do we do that? Start right now by ensuring that the current fascist administration does not persist past these next few years. That will be an incredibly difficult task, but it must be done. Beyond that, we do all we can to eliminate the use of fossil fuels and to protect and rebuild life on Earth.

For more on the AMOC collapse, the Post article and the original study from a year ago are good starting points, as are an Inside Climate News piece, a Guardian article, and a collection of responses to the study from various experts, gathered by the Science Media Centre.

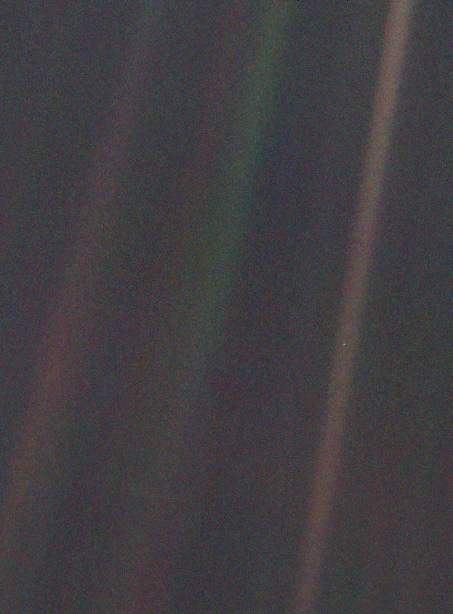

Finally, I’ll close by regifting a Valentine’s Day present handed out by the SETI Institute. The Pale Blue Dot photo was taken by Voyager I on February 14th, 1990, 6.4 billion km from Earth as the craft was leaving the solar system. “Look again at that dot,” Carl Sagan wrote.

That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.

The dot is much more than that. It’s the very idea of life shining brightly against the emptiness of space. It is also the future of life, a future that we are now defining by our decisions and indecision. We must proceed with wisdom and with caution, because the entire community of life, of which we are merely a part, will live out their lives on that dot too.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From

and The Weekly Anthropocene, a great interview with the brilliant utopian science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson. Most fascinating, perhaps, is the work that Robinson is doing as part of a scientific and engineering coalition that wants to try to prevent catastrophic ice loss in the Antarctic. This work follows up on one of the ideas in his excellent and influential recent novel, The Ministry for the Future.For another dose of sanity, read the interview at Yale e360 with Robin Wall Kimmerer about her new book The Serviceberry and the idea of evolving our market economies into gift economies, modeled on how the natural world works.

From DeSmog, a report on an unholy coalition of right wing religious groups, fossil fuel executives, climate-denying organizations, prominent Trump administration officials, and Project 2025 authors meeting in London to “re-lay the foundations of civilization.”

From

and The Crucial Years, an under-reported story about the Trump administration using tariff threats to strong-arm several nations into ordering large quantities of LNG as a way of justifying the build-out of more unnecessary, harmful, and generally stupid LNG export facilities on the Gulf coast.From the Times, a first-ever National Nature Assessment commissioned by the Biden administration was just weeks away from publication when Trump ended the effort by executive order. The 150 scientists and other experts involved, who spent thousands of hours on this vital task, are committed to publishing it anyway.

From bioGraphic, juvenile lobster populations in the Gulf of Maine have been dropping steadily for a decade. The reason seems to be a warming-related mismatch between their emergence and that of their primary prey.

From Grist, a community effort in Altadena, CA, to replant fire-resistant native species in the wake of the recent devastating fires.

Your essays keep getting finer just like that ascending violin passage in Brahms violin concerto. The picture of the swing was so evocative and apropos of our situation. The AMOC will definitely collapse or at the minimum significantly fray at its northern extension. Hotter than expected sooner than expected is the mantra of the times. So unfortunate that our own country's current leadership is blind to the dangers. But Jason, we are already past the tipping point. The chair is already falling and it may take centuries to reach the floor, but it is beyond our power to set it back upright- we can only mitigate the damage for the sake of our distant grandchildren. We owe them that and your newsletter plays a role in the effort

Very informative, Jason. Especially with the addition of the Thermohaline Circulation video. The ’Pale Blue Dot‘ photo, and Carl Sagan’s quote, with the addition of your own;

“We must proceed with wisdom and with caution, because the entire community of life…”

“Wisdom and with caution…” are only words without meaning for the next four years of America’s leadership. I can only hope other countries will be temporarily taking ‘our’ place and doing the work that this administration will most certainly ignore.