Scraping Bottom

6/13/24 – Bottom trawling is one of the least-known of the most destructive things we do

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read this week’s curated collection of Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

In 1376, during the reign of Edward III, a petition to Parliament asked that the authorities study the great harm being done in local waters by a “wondy choum,” a fishing device with a net of such fine mesh that when dragged over the sea floor “no manner of fish, however small, entering within it can pass out and is compelled to remain therein and be taken.” Worse, the wondy choum “destroys the spawn and brood of the fish beneath the said water, and also destroys the spat of oysters, mussels, and other fish by which larger fish are accustomed to live and be supported.”

This 14th century device caught so many fish that the fishermen “know not what to do with them, to the great damage of the commons of the kingdom, and the destruction of the fisheries in like places.” The communities who lost their productive fisheries, in this petition to the king, “prayed remedy.”

Today, 648 years later, the descendants of the wondy choum are very, very busy, and a goodly portion of the oceans are now in need of a remedy.

Heather and I have been dining on cod this week. The fish was “wild caught, frozen at sea,” according to the label slapped on the package at the supermarket fish counter. But this five-word story doesn’t really capture how our food reached us.

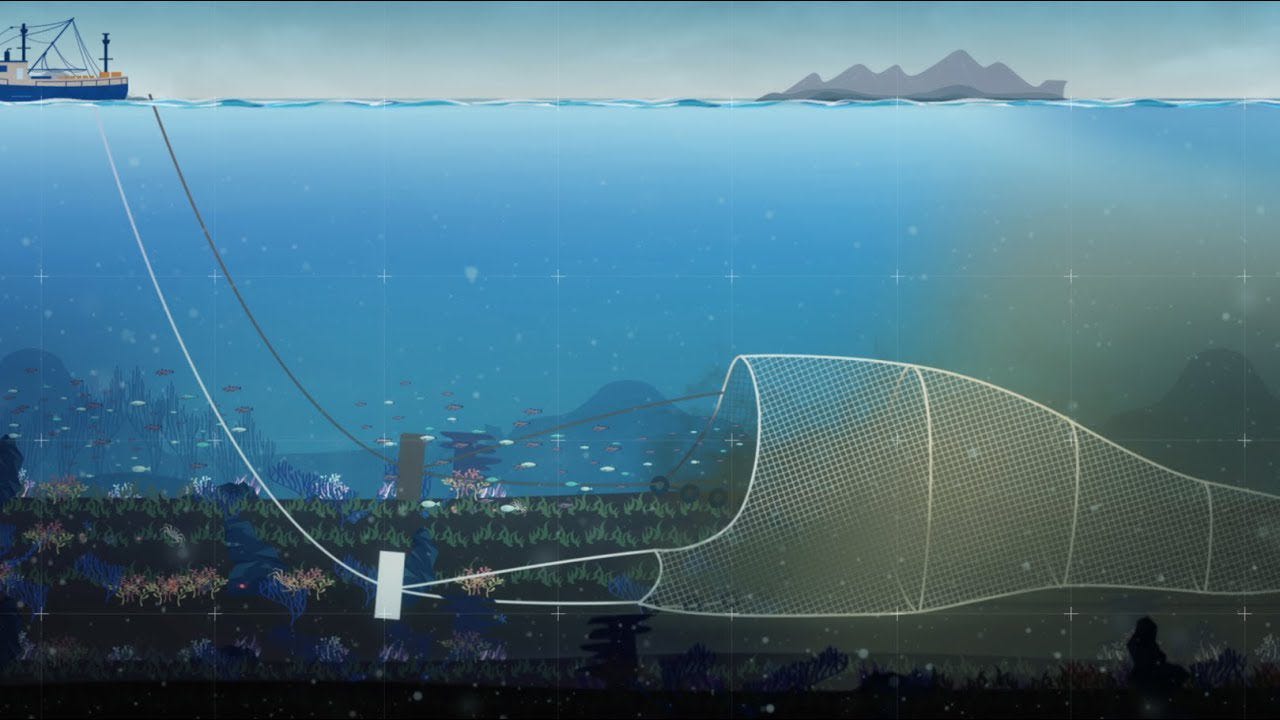

One of the answers to the question Where did the fish on my plate come from? is this: A quarter of the world’s wild seafood catch is captured using a fishing method that has a long history of brutally destroying seafloor ecosystems. Imagine simultaneously clearcutting and tilling wide swathes through a forest while capturing nearly every living thing in your path and jamming all of it into a massive net. Now imagine doing it over and over on different paths through the same habitat. That’s bottom trawling, in which a weighted net towed behind a large fishing boat drags its way across the once-lush diversity of habitats on the sea floor.

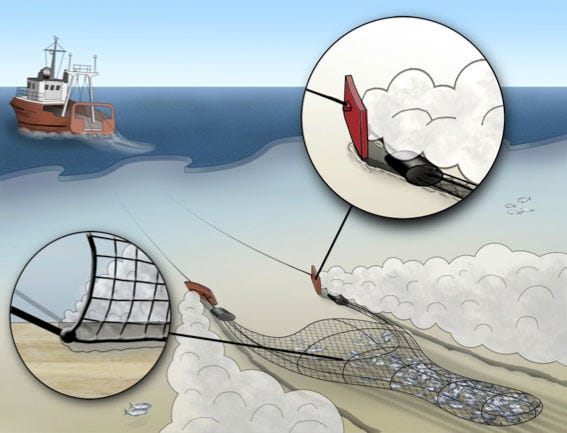

In his extraordinary article on Earth’s mass extinctions in the Atlantic back in 2017, Peter Brannen wrote that every year, across the globe, bottom trawlers “plow an area of seafloor twice the size of the continental United States, obliterating the benthos. Gardens of corals and sponges hosting colorful sea life are reduced to furrowed, lifeless plains.” According to Oceana, 580 square miles of seabed are destroyed each day by high-seas bottom trawlers. If this seems extraordinary, Oceana reminds us that “the mouths of the largest nets are big enough to swallow a Boeing 747 jumbo jet, and trawls and dredges can destroy century-old coral reefs in mere moments.”

According to

, author of the excellent Ecologist@Large newsletter here on Substack and a Fishery Research Biologist for NOAA for 22 years, bottom trawlscatch virtually everything in their path (except those organisms that can escape or avoid it), and if they touch the bottom, they wreak havoc by damaging seafloor organisms, especially corals and other “emergent epifauna” that stand erect from the seafloor.

Too much of Earth’s continental shelves, particularly around Europe, have been subject to this erasure, year after year, repeated at a rate much faster than the ecosystems can fully recover. And increasingly, larger ships trawl deeper waters, down to 1,000 meters, where life is particularly fragile and much slower to recover. Corals and other deepwater communities require far more time to rebuild than human hunger and human impulses will allow.

The goal of bottom trawling is to harvest the marketable species which live on or near the seafloor. As I understand it, this is mainly types of whitefish (cod, haddock, pollock, hake, hoki, etc), groundfish (flounder, halibut, sole, etc), as well as squid, shrimp, rockfish, crabs, skates, and others. But many other species, from coral to turtles, dolphins, and sharks, can be caught and die in the net or aboard the vessel before being thrown overboard as useless bycatch.

Like all the other global and existential threats to the Earth’s oceans in the Anthropocene – overfishing, warming, stratification, acidification, deoxygenation, mining, noise, ship strikes, to name a few – the killing costs of bottom trawling are largely invisible to us. But we’re now realizing that scraping bottom may pose another major threat to planetary health by mucking up carbon sequestration in the oceans. That CO2 imbalance may also be invisible, but its consequences are not.

Let’s back up and look at a pair of very short videos – one is an anti-trawling explainer from Oceana Europe and the other shows us a fish-eye view of a trawl – and then I’ll offer up some notes on the problems inherent to this common practice:

Habitat loss

A habitat is an environment structured by both physical features and the innumerable relationships between the species who live there. When the structures of the terrestrial habitats we’re used to – forests, wetlands, grasslands, ponds, etc. – are razed by the bulldozers of human expansion and extraction, we see the erasure. In the seagrass meadows and coral communities and other habitats on the seafloor, where the bulldozing happens beyond our senses, the same erasure occurs. The result is biodiversity loss, desertification, and living communities severely disrupted as all the details of home are uprooted, dispersed, or harvested.

Bottom trawling is less damaging if restricted to less biodiverse seabed, like those that are sandy or muddy. And, to be fair, trawlers often prefer these conditions because a smooth seabed doesn’t pose a threat to their equipment. But these are still delicate habitats that take many years to recover. Sediment is still habitat, and it’s formed over long periods. A 2014 study found that bottom-trawled seabeds “resemble the catastrophic effects caused by man-accelerated soil erosion on land and the general environmental deterioration of abandoned agriculture fields exposed to high levels of human impact.”

One thing to remember about the bottom trawling industry is that, unlike some harvesting industries here on land, they have no obligation to restore the habitat they impact. They may be regulated or limited in various ways, but they’re not down on the seabed replanting corals or breeding threatened species back into abundance.

When I talk about corals being destroyed, I’m not really talking about coral reefs, which aren’t a friendly habitat for a fast-moving net. I’m referring to standalone or small communities of corals like the one in the picture above. One piece of information I found on this is from a Greenpeace campaign in NZ to ban bottom trawling, which notes that in 2020 NZ trawlers – a tiny portion of the global trawling fleet – destroyed up to 3,000 tons of deepwater corals.

The Ecologist@Large makes a fascinating sidenote observation to the story of benthic habitat destruction: Even the small buoy-connected traps set for lobsters and crabs can act like little plows when storms and currents move them. And there are millions of them.

Bycatch

“Bycatch” is the term for the fish, mammals, corals, shellfish, vegetation and other species caught by accident. The process of being caught, squeezed by thousands of pounds of other fish, and dragged to the surface and dumped onto the deck of a ship before being sorted turns much of this bycatch into dead meat dumped back overboard. In the trawling industry, the scale of bycatch – which is really a euphemism for inefficiency, waste, and cruelty – is staggering.

Bycatch exists because life in the ocean lives in communities. You can’t run a jumbo-jet-sized net through a community and catch only one species.

As that 14th century complaint to Parliament made clear, mesh size matters. This is one of the fundamental features of trawling regulation. A larger mesh gives juvenile fish a chance to escape. Other devices now in service either prevent the wrong species from entering the net or provide opportunities to slip out.

Oceana notes that “bottom-dragging trawlers in the North Sea catch 16 pounds of marine animals for every pound of marketable sole that is caught.” And “in some shrimp trawl fisheries,” according to Transform Bottom Trawling, “research suggests that levels of bycatch may be as high as 80-90%.”

A 2018 NPR article looked at a study that found from 1950 to 2015 the global fishery catch was nearly double what had been reported – 25 million tons rather than 14 million tons – with about half of the unreported haul being bycatch.

Destruction of small-scale sustainable local fisheries

One of the missions of Transform Bottom Trawling is to push nations to develop policy which prohibits bottom trawling in inshore waters, which subsistence and small-scale fishing communities (more than 100 million people) rely on for their daily food and livelihood.

Sediment resuspension and sediment loss

The trawl “doors” that keep the front of the net open, and the bottom edge of the front of the net, are the two parts of a bottom trawl that touch and disturb the seabed. Primarily it’s the doors that gouge deeply into the sediment, churning up plumes that scare fish into the net but leave behind long-term scars and a host of other problems.

A 2016 USGS newsletter reported on a study, “What a Drag: The Global Impact of Bottom Trawling,” which found, among other things, that bottom trawling was “essentially rototilling the seabed,” and by doing so created a six-fold increase in sediment loss from continental shelves. Stirring up all that sediment changes everything, including the ability of filter-feeding animals and photosynthesizing plants to survive:

Resuspending bottom sediment changes the entire chemistry of the water, including nutrient levels. Resuspended sediment can lower light levels in the water and reduce photosynthesis in ocean-dwelling plants, the foundation of the food web. The resuspended sediment is carried away by currents and often lost from the local ecosystem. It may be deposited elsewhere along the continental shelf, or in many cases, permanently lost from the shelf to deeper waters. Changing parts of the seafloor from soft mud to bare rock can eliminate those creatures that live in the sediment.

The carbon problem

Looking at bottom trawling as a carbon problem is a little complicated. First and most obviously, it’s a very carbon-intensive form of fishing in terms of fuel use, especially when the gross inefficiency (bycatch vs. intended catch) is taken into account. Fishing vessels of all sizes are heavy and slow, and deepwater fishing grounds can be hundreds or thousands of miles away.

Deepwater trawling is so costly in its fuel use, in fact, that the industry’s fuel costs have been subsidized by governments in exchange for continuing to bring more fish to markets. The subsidy estimate for all the high-seas trawlers – those operating in deep waters outside national economic zones – is $152 million per year, about 25% of the value of the fish those fleets are landing. These subsidies have the perverse effect of encouraging inefficient resource use.

Second, when trawling destroys kelp forests or seagrass meadows, they’re wiping out biodiverse ecosystems that also sequester significant amounts of carbon. Seagrass meadows, in fact, absorb carbon 35 times faster than tropical rainforests.

Third, and this is where things get interesting, a 2021 report estimated the amount of carbon released from the sediments that trawling stirs up and determined that it was more than the annual emissions of all global air travel. At the time, the debate over this finding assumed that all of that carbon remained in the ocean, binding with oxygen in the water to form CO2 and contributing to ocean acidification, but not reaching the atmosphere. In 2024, though, further analysis found that 55-60% of the carbon would rise to the surface and enter the atmosphere within nine years. (The other 40-45% still contributes to acidification.)

A Mongabay article explains that, if verified, the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere by bottom trawling would be “nearly double the annual emissions from the combustion of fuel by the entire global fishing fleet of about 4 million vessels.” But I should note that the both the 2021 and 2024 studies have been criticized for possibly overestimating how much carbon from the seabed bottom trawling is releasing.

So, to sum up, bottom trawling has been a nightmare for ocean biodiversity at the same time it may contribute significantly to the heating of the planet and the acidification of the oceans. This sounds like a fairly obvious lose-lose proposition, but as the cod filets on my plate suggest, bottom trawling is an operation that employs millions and feeds a burgeoning human population. It needs thoughtful, precautionary regulation around the globe. It should probably be banned in deep waters and prohibited from Marine Protected Areas, but it’s not going away anytime soon.

And, surprisingly, despite everything I’ve told you here, bottom trawling is an operation that is increasingly seen as sustainable, at least in the parts of the world that have pushed to fix its problems. How we define “sustainable” may be part of that conversation.

And that solution-focused side of the bottom-trawling conversation is what I’ll talk about next week.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

I’ll start with another ocean story, this one a fun report on a terrible idea: From John Oliver and Last Week Tonight, a deep dive on the terrible, ocean-altering prospect of deep sea mining. Oliver, with his usual brilliant wit, dismantles the idea that violently disturbing the sea floor in the largely unexplored abyssal plain is a) ecologically rational, b) appropriately regulated, and c) necessary for the renewable energy transition. Some of you will recall I made the same argument a few years ago in “Still Digging.” The Guardian has a good review of the Last Week Tonight episode, and highlights some excellent bits of Oliver’s monologue, like these:

“Ultimately, it’s going to take us having the patience to wait for the science on this and the discipline to actually listen to what it has to say,” he said. “And I know that that’s hard to do, because it’s so much easier to just pull out a rock and call it the savior of humanity.”

Nevertheless, “it is beyond time that we stop treating the deep ocean as something to exploit,” he concluded, “and start treating it for what it really is: a mind-blowingly vast, virtually unknown world within our world.”

From Civil Eats, the pervasive problem of “plasticulture” farming, the very common practice of using plastic sheeting to suppress weeds and keep moisture in the soil. As a result, microplastics are common in farm soils, and we’re only beginning to understand the impacts of that.

A related article from Inverse explains just how bad and infuriating the food waste problem is in the U.S., and illustrates it with four charts. Food waste is endemic throughout the system, from growing to transport to consumption. Here in the U.S., if we could reduce it by even a small portion, one activist explained, we could make a huge difference: “There's over 100 billion pounds of produce waste in this country every year,” he said, and “we only need 7 billion to drive food insecurity to zero.”

From the Guardian (and their indispensable Age of Extinction coverage), the form of water contamination that too few of us are aware of: pharmaceutical pollution. Addiction, sex reversal, and a variety of significant to severe behavioral changes have all been observed in fish and other species that feed on those fish (that’s us too). Waterways around the globe are contaminated with a wide range of drugs, including antibiotics, caffeine, anti-anxiety medications, antidepressants, antipsychotics, cocaine, and methamphetamine. Neither industry nor government seem to have any plans to address this.

From the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology, are you interested in living in an ecological civilization? Check out the Forum’s comprehensive site on the idea, which includes reports, books, multimedia, articles, journals, and links. I haven’t explored it yet, but am hoping it’s a rich trove of thought and philosophy on how we get from here to there. Let me know what you find.

I’ve been digging into my neglected inbox, and here’s an excellent older piece (from last September), “Burning for Water,” from

and The Climate According to Life that beautifully captures Rob’s climate focus – that it’s as influenced by the green world as it is by carbon emissions – as he drives across the western U.S. and explores forests and what we’ve done to them. It’s a travelogue, and it’s the story of how we must regenerate life on Earth if we want to stabilize its destabilized atmosphere.And while I’m offering throwback recommendations, here’s another from last year from Orion that involves two of my favorite writers: “Geography as Generosity,” a short essay from Robert Macfarlane on the life and legacy of Barry Lopez. Originally published in From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry Lopez, the essay beautifully evokes the unsurpassed care and capacity that Lopez had in describing landscapes and our relationships with them. It’s worth reading just for the beauty of Macfarlane’s prose too.

From Rewilding, a feel-good work-hard story about a woman who has transformed a part of Melbourne, Australia, with a community effort to plant street-side pollinator gardens.

Demand generates suppliers. If we stop consuming fish and marine protein, the mining and scraping will cease. But we won't do that will we? So they will continue. De-populate please! One solution will cure a thousand ills.

Jason and your people,

If not for Sylvia Earle and Ayana Elizabeth Johnson's work, I would have been as shocked about bottom scraping as when I first learned of the brutality of clearcutting.

The 2024/2025 factory size boats slated to launch from China will accelerate the destruction.

How amazing that you and my other favorite Thursday Substack writer @jannisse ray referenced Robert Macfarlane's Orion article about Barry Lopez.

I will read your links. in kinship, Katharine