For the quotation of the week, I suppose I should offer up the little scrap of hope embedded in the final agreement at COP28, a sentence recommending that the world should be

transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner.

As Bill McKibben points out in a piece titled “What Can We Do with a Sentence?”, the line itself is meaningless until activists give it meaning. He explains that, as with a sentence in the 1995 IPCC report that begrudgingly admitted human impact on the climate, and a sentence in the 2015 Paris accords that pledged to aim to keep global heating less than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, one sentence can be an important tool for activists to wield. These sentences are ridiculous in their tiny truths, but they are tiny truths on a grand scale, and so become levers to use every day to turn larger truths into policy.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

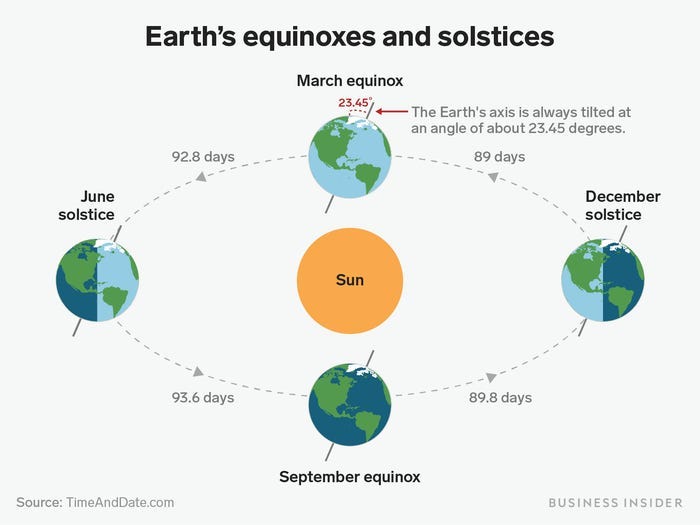

The December solstice occurs next Thursday, Dec. 21st, at 10:27 p.m. EST (UTC -05:00) here in the U.S. It’s the shortest day and longest night of the year in the north, as the setting sun reaches its lowest point in the descending path it began last June. The solstice has long been envisioned as the moment of stillness before the sun promises us the gift of its new path, a slow ascent back to warmth.

If you have a moment to contemplate the moment, perhaps it’s a time to think about light and life, about the inevitable loss and struggle we associate with darkness even as we cozy up within it, and about the equally inevitable return of the sun to the horizon.

Those of you reveling in the long days of abundance and warmth in the southern hemisphere will note my bias here toward the long-shadowed north, as we settle into the longest and coldest nights of the year. But you’re on a cusp too. In the midst of your abundance the sun begins its descent. Both June and December solstices offer a moment to weigh our place in the larger, more-than-human realities of orbit, spin, and ecology.

My wish for us all is that we take notice of the light, embrace the darkness that contains it, and recognize the gift for what it is. That recognition necessitates both gratitude and responsibility, too, as we work to rebalance the community of life we’ve disrupted in recent centuries. The Earth’s tilt, spin, and orbit are inevitabilities, but what happens amid the greenery and oceans is now largely up to us. One good working definition of the Anthropocene is that humans are, for the foreseeable future, setting the conditions for life on Earth. The scale of our population and resource use means that what we do, or neglect to do, matters to every other species.

Beginnings and endings, for which a solstice has been a symbol since the most ancient of human times, are no longer what they used to be. It’s up to us to ensure that what the sun rises to warm is still lush, complex, diverse, and autonomous within the outsized spread of civilization.

The light that’s coming will bring with it the memory of sustenance and the promise of life to carry us through the hardest months that still lie ahead. Even now, seeds and rootlets embedded in the living soil – vast communities of microbes, fungal mycelia, insect larvae, worms, and much more – are prepared, when light and warmth release them, to grow restless and then to grow with a full-bodied embrace of the sun.

Up here in the slant-lit north country, the solstice is a good night for a fire, but what shall we burn that we aren’t already burning? Coal, oil, gas, wood, forests, landscapes, communities are aflame. We live, by one reckoning, not in the Anthropocene but the Pyrocene, an age of fire.

At this cusp in both human and Earth history, we have a choice: Shall we continue to burn the tree of life (and thus the furniture of civilization), or shall we instead kindle our love of life, fan the green flames of a rewilding planet, make a bonfire of those companies and ideas which have sacrificed the world, and then smolder through the transformation until life returns to life?

My friend Nina McLaughlin has written a pair of gorgeous long-form essays on the solstices for the Paris Review (where she has been a frequent contributor). Both have been published as slim books by Black Sparrow Press for Godine, with Winter Solstice appearing this fall. Nina’s writing is beautiful, brilliant, sensitive, sensuous, and intimate, conveying both the darkness that looms and the spark that warms. Here she is on the virtues of heating with wood:

To share a room with flame is to feel a living presence in the room with you. As Basho writes:

Fireplace

On the wall

A shadow of the guest

Guest present and guest past, guest seen and unseen. Who do you invite in on the longest night? What visitors arrive? The soul is thicker in winter. Thick enough to cast shadow on the wall.

And here’s Nina on the magic of the season:

We know the angle of the axis on which our earth spins, we know the core of the sun burns at twenty-seven million degrees Fahrenheit, we know our life would not exist without it, we need its return, and it will return. We know so much. There are so many facts. And right alongside them, a whole world we can’t explain or comprehend, which we cannot give words to, an understanding of presence and goneness, of departure and return, the haunt and mystery, we see it and sense it but cannot say it. And this is the magic, the incomprehensible unsaid, this is the beauty in this dark moment of the year, what we see without seeing. The ornaments coming alive, the ghosts who dug a tunnel under the earth for the sun to enter on the solstice, the silent moon, the snow-white swans, the glittering starts, the twinkling lights on the trees and in the windowsills, behind the eyes of the people we love. This is the magic that glows, that lives alongside the facts, that burns and lights the dark. This dark season, as light presses its way back to us, offers it to us.

Celebrating the solstices as gifts has a deep history going back to Neolithic times, at least. The traditions we call Christmas, Hanukkah, Yule, Dongzhi (in China), Yalda (in Iran), and many more are rooted in our ancient habit of attending to the gift of light, which is the gift of life.

Yet I’d be remiss if I didn’t note that solstices are a high-latitude story, not a tropical one. Three billion people, about 38% of our population, live in the tropics, where solstices erase shadows as much as they lengthen them. If you stand on the Tropic of Capricorn (23.5° south of the equator) at solar noon on the December solstice, you’ll experience a “zero shadow” day, with the sun directly overhead. The only way to see your shadow is to leave the ground. Likewise with the Tropic of Cancer on the June solstice. On the equator, you can experience two zero shadow days, on the March and September equinoxes.

The source of the Anthropocene has also been a largely high-latitude phenomenon, as we in the north have been the source of shadow rather than light. Tropical cultures are being hit with the brunt of the hotter world we’ve combusted in our engines, and the loss of their forests and biodiversity is almost all due to the darker forces of colonialism, white supremacy, and foreign-owned industrial extraction.

It’s incumbent upon us in the north, then, to be first among equals in phasing out fossil fuels, building new energy systems, replanting forests and grasslands and wetlands, making agriculture sustainable and nontoxic, reducing consumption and reusing/recycling resources, funding global adaptation and mitigation and nature-based solutions to both the climate and biodiversity crises, and much more. We need to bring light to wherever we’ve cast our long shadows. As the late-winter sun brings minutes and then hours back to the day, so should we rapidly increase our efforts to mend what’s been broken. By all accounts, we only have years to fix the harm of centuries.

Every ecological community is a conversation about light – absorbing the sun’s energy, passing it around, converting it into cells, bodies, and soil – and we need to rejoin that conversation instead of crushing it beneath our wheels. It’s a cultural decision, not a technical problem.

The solstices are a structural feature of the movement of the spheres. Humans, for all our noise and fury, are one set of souls among many aboard one of those spheres, still staring upward and wondering at the movement that giveth and taketh light. We can sing about it, as this essay tries to do, but we’re still fragments of biology in a universe of physics.

That doesn’t make us unimportant, only small. The light that’s returning is already within us.

And really, it’s not the light that’s returning. It’s us and our place on the living, spinning, orbiting sphere that’s turning back to the light. The light never left, never moved, never blinked. The sun is always standing still. Earth is the tumultuous one in the relationship, and humans are the children spinning tales about the tumult.

Now we need to spin new tales about our long-term return to the light, tales that will guide us into centuries of sensible, sensitive, sustainable living. For now, we may only have sentences buried deep in global treaties – “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner” – to start with, but while our bodies may be made of stardust and light, our consciousness is made of stories. We can build (or destroy) worlds with a single sentence.

And finally, in writing about the solstice, I feel compelled to remind you of something I offered readers last year at this time: a link to a documentary by Emergence on the great and wise writer Barry Lopez, and some of what he had to say. My first writing for the Field Guide, 139 weeks ago, was a long piece that memorialized Barry, whose lifelong task was to articulate with brilliant insight and elegant prose our broken and yet still beautiful relationship with the natural world. Here are two samples of Barry speaking from the documentary:

I think one of the reasons our lives are difficult is because of this separation we’ve insisted on from the rest of the natural world and our insistence on the primacy of human life. Human history is but one dimension of natural history. It’s not the other way around.

What is our ethical relationship with the world outside ourselves? The sign of where it goes wrong is when the world outside the self is no longer the companion but the servant.

If nothing else, the solstice reminds us that the world outside the self is spinning in orbits greater than our own. We would do well to seek its companionship.

In a more literal use of the term “solstice gifts,” I thought I’d recommend some reading material for you to gift yourselves or others in this holiday season. I’ll start at home, with a few excellent books by friends of mine:

Nina McLaughlin’s beautiful Winter Solstice and Summer Solstice, as described above.

Jennifer Lunden’s masterful American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life, is a “Silent Spring for the body,” a remarkable memoir, a literary mystery, and a beautifully-written indictment of the toxicity of our daily lives.

If you’re fascinated with penguins, Jim Mastro has co-written Journeys with Emperors: Tracking the World’s Most Extreme Penguin, which narrates and illustrates an extraordinary story of difficult research done to document the lives of these mysterious creatures. There’s a whole series of supplemental short videos of Emperor penguin activity which you can check out too.

One of the sad little secrets of writing the Field Guide is that I rarely take the time to read the books I want to read. I spend far too much time staring into this screen reading articles, essays, newsletters, and studies, and far too little on the couch absorbed in the printed page. Nonetheless, I have managed to read a few recently, and highly recommend these two:

The Ministry for the Future, by Kim Stanley Robinson, an astonishingly good, gritty-but-still-utopian, near-future science fiction novel that imagines a way forward through the wicked problems posed by the climate and biodiversity crises.

Ways of Being – Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence, by James Bridle, which I mentioned last week in a piece on corporate AI. Bridle’s work here is fascinating and necessary. Our notion of intelligence(s) needs serious readjustment, and the effort here to describe a continuum of intelligence from plants to AI is well worth your time.

I amuse Heather by buying all the books I want to read and let them pile up precariously next to the couch. If only proximity was activity, I’d be very well read… Here’s a list of new books that I’m excited to read, and which I’ll recommend to you because I’m confident from my research that they are excellent, important stories:

Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of Our Planet, by Ben Goldfarb, is a book I wish I’d written. I did do a three-essay deep dive into road ecology a while back, and am really excited to read this. (I still want to read Goldfarb’s previous book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers, and Why They Matter, not least because I also did a fun and fascinating three-essay series on beavers too.)

The End of Eden: Wild Nature in the Age of Climate Breakdown, by Adam Welz, examines in detail what the hotter world we’re making is doing and will do to the community of life. Nearly all conversations about climate chaos focuses on human impacts, but species everywhere are suffering.

The Heat Will Kill You First, by Jeff Goodell, is a best-selling nonfiction book about the worst and most immediate consequence of climate change, the heat that will soon make many lives unlivable. The link I’ve provided here takes you to a long sample from the book at Orion. It makes a great companion piece to the disturbing opening scene in Ministry for the Future.

Gods, Wasps, and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees, by ecologist and journalist Mike Shanahan (who has a Substack I describe below), takes us into the remarkable biology and ecologically redemptive qualities of fig trees. The book looks fascinating.

If you’re looking for the best deal in town on a Substack that’s doing vital work for reconnecting us to the natural world, please consider becoming a paying subscriber to Chasing Nature, by Bryan Pfeiffer. In recent days, Bryan has announced a host of benefits for paying subscribers, including “video seminars, wildlife maps, and a way to share sightings from nature with Bryan and the Chasing Nature community.” His video seminars on birding and photography, and his field guide to field guides, are invaluable all on their own. Bryan is at the top of his game as an ecologist and a writer, so if you haven’t already read and supported his work, I highly recommend you do so.

Finally, and reluctantly, in what I suppose is a gift to myself… I have decided to allow a subscription option for Founding Members. A few people have inquired about it in recent months. I’m not fond of telling people that they can throw money at me, and I’m concerned that friends and family will take the opportunity to pay more than I’m comfortable with. But such are the tensions of a writer’s life…

The Founding Member subscription is set up to accept anything above the standard $70/year, up to a disturbingly high $200/year. For now, as with standard paid subscriptions, there are no particular benefits to founding subscriptions except the honor of being so wonderful and the gratitude of a hard-working writer. It’s been important to me to keep the Field Guide, including the archive, free to those who cannot afford a paid subscription. That said, if at some point I offer extra services like read-alouds or podcasts, I may set those aside as special benefits. We’ll see.

That’s all for this week, folks. Thanks for being here. I’ll be in your inbox again on the solstice.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Here’s a variety of reporting on and responses to the hotly-contested, sort-of-consequential outcomes of COP28 from Carbon Brief, NPR, the Guardian, Human Rights Watch, Conservation International, and the Times. I should have a lot more to say on the topic next week.

A shout-out to Sam Matey at The Weekly Anthropocene and his year-end celebration of the good news in 2023 on the energy and biodiversity fronts. Sam’s work is vibrant and optimistic – he uses more exclamation points in one newsletter than I use in a year – but there’s plenty of room in this discussion of how we heal the disrupted world for glass-half-full announcements amid my glass-is-on-the-edge-of-the-table observations… Anyway, read Sam’s 2023-in-review and take heart at some good work being done.

Likewise, The Nature Beat is a new arrival on Substack from

, who is an incredibly experienced and well-informed journalist on the environmental and biodiversity beats. Check him out.From the Times, who your cat is eating while outside. A new study has radically increased the list of known species – more than 2,000 – on the kill list for cats. Want to take a big step to support biodiversity? Please, please, please: keep your cats inside, and support efforts to remove feral cats from the wild.

From Hakai, a beautiful, incredible story of rewilding the Danube delta in Ukraine. Yes, even in wartime, a remarkable effort is underway to restore a huge and vital ecosystem.

From the Guardian, nearly 1500 climate scientists are begging you to become a climate activist. Scientist Rebellion, a group linked to the vital Extinction Rebellion movement, published a letter during COP28 asking us all to

Join or start groups pushing for policies that help secure a better future. Contact groups that are active where you are, find out when they meet and attend their meetings… If we are to create a livable future, climate action must move from being something that others do to something that we all do.

From Al Jazeera, the mindboggling carbon footprint (and other large-scale environmental damage) of the U.S. military, and how “the 800-pound gorilla of military emissions” is not accounted for in the usual discussions (and negotiations) of the U.S. contribution to global climate chaos.

From NPR, a quick primer on why fossil fuel companies have no real incentive to invest in renewable energy. Until the profit margins on selling oil and gas are cut hard, they’ll focus on their core business model. The switch away from fossils is coming, but not soon enough.

From the Atlantic, what happens to all that stuff we return, especially around the holidays? Read this disturbing deep dive into the world of “reverse logistics” to find out.

From the LA Times, a push to represent more of the natural world in emojis is rooted in an effort to raise awareness of the biodiversity crisis. If people are using emojis of tardigrades and damselflies and amoebae, for example, there will be more conversation in the digital world about the real one. Most animal and plant emoji are vague representations of whole genera (conifer) or they’re images of popular vertebrates, even though those animals make up a small percentage of the living world.

Aw, shucks — thanks, Jason, for the shoutout. And, as always, thanks for thinking and writing on behalf of the planet.

Thanks, Jason for the many solstice gifts! Not least of which, these lines of yours:

“The light that’s returning is already within us.” (Oh my!)

“And really, it’s not the light that’s returning. It’s us and our place on the living, spinning, orbiting sphere that’s turning back to the light. The light never left, never moved, never blinked. The sun is always standing still. Earth is the tumultuous one in the relationship, and humans are the children spinning tales about the tumult.”

🙏