Hello everyone:

After last week’s heavy political piece on Project 2025, and the previous three-week deep dive into road ecology, I thought I’d offer you something a bit lighter this week, an exploration of our abiding love for the natural world. And, I should explain, I have another big writing project this summer that has been inspiring me to keep reaching back into the archives to offer work that few of you have seen. (I’ll tell you more about the writing project soon.)

I first published this essay back in January of 2022. It has been updated and edited.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

In her beautiful essay, “Heal-All,” (from Nature, Love, Medicine: Essays on Wildness and Wellness), Robin Wall Kimmerer inspires this question: When we talk about the Earth, would we rather describe the fabric of life as a web of interconnected lives and relationships, or as a collection of mere things? Do we live in a community or in a warehouse of objects? Easy answer for me, and for you too, I imagine.

But what if we defined life here to include “inanimate” wonders such as stones, rivers, and landscapes? What if all animate life and inanimate features of the landscape were granted personhood by the language? Are you comfortable saying of an aphid that "he’s eating the roses" or of an apple tree that "her blossoms fell to the ground" or of a river "she flows beautifully"? In English, we do some of this already, most often when we speak with traces of folk tradition or a sense of poetry ("she sails beautifully," we might say of a boat), or when from nearly any culture we refer to the Earth as feminine. But the moment we want "accuracy" or "objectivity," English demands that we revert to our universal "it."

Gender isn't my point here. What interests me is the acknowledgment of the erasure we unconsciously inflict every time we refer to anything in the living world as "it." Kimmerer writes in "Heal-All" that

When I'm passing through the meadow on a summer morning and encounter the one who woke me to bird song or the one who gives me my healing tea, when I am on my knees picking Prunella [Heal-All], who faithfully places herself in my path – calling them all "it" feels wrong. The grammar of English reduces the natural world to "things" and thus opens the door to exploitation.

In my native Anishinaabe language it is impossible to speak of plants or animals or rivers or mountains as "it." We refer to them with the same grammar as we do our own families, because they are our families. Because they are understood as persons, we speak of them as persons. We speak with a grammar of animacy.

I'm not writing this week to advocate for a fundamental shift in English. I'd love to see that change, but uprooting the objectifying pronoun from English would be the equivalent of a heart transplant for the language. It would probably be easier to turn petrochemical companies into organic florists (another fine idea). What moves me is the worldview Kimmerer – a botanist, ecologist, professor, and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation – so beautifully articulates from her vantage on the meeting ground between science and indigenous knowledge. Her love for the natural world is contagious.

That worldview, the one that understands Heal-All to be a person with a remarkable gift of medicine (antiviral, antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, and more) for other persons, including humans, is based in love. Love of the family we call plants and animals, as she says, but mostly love for the natural world in its complexly woven beauty. Love, Kimmerer says, even in the face of the Anthropocene:

It's risky, though, to love the world, in a time of climate peril. Your heart could get broken. The places and beings we cherish are evaporating before our eyes... But the plant teachers remind us that often the cure grows near to the cause. The cause for the fear and the pain of loss is the love we bear for the land. And love, we know, is the cure for loss, the antidote to fear. Love is the medicine when it changes us, and we change the world.

We can all point to cherished places and beings we’ve lost to the ever-widening human onslaught – childhood forests, family farms, favorite species diminished nearly to the vanishing point – and so we can each speak of our hearts breaking. And there are the images from around the harrowed world arriving day after day, throughout each year, of what Neil Young described a half-century ago as “Mother Nature on the run.” There’s so much devastation, at every level. But in her essay Kimmerer does a fine job of placing the tumult of our fear and loss squarely where it belongs: within the gravitational pull of love.

This is not some plaintive Can’t we all just get along? wishful thinking. This is the intelligence of empathy and the wisdom of community. Kimmerer establishes an ethical framework for our relationship with reality and calls out the ways in which language either undermines or sustains that relationship.

To do this, she makes a metaphor of the folk truism that remedy plants often grow near the plants which cause harm, like jewelweed near poison ivy. Our suffering in the face of these ecological losses reminds us that we still love the natural world, even in the midst of all our civilizational delusions and distractions.

We suffer because we love. The cure is to love more.

The Greek root “-philia” is attached to nouns to identify, most often, an emotional attachment to that noun. Bibliophilia is a love of books, while Francophiles devote themselves to all things French. (Hemophilia, though, is a tendency to bleed rather than a fondness for blood...) There are shades of meaning here – affection, tendency, desire, attachment – but –philia is generally defined as love. If we blend these shades together and apply them to our place in the fabric of life, we arrive at what the great E.O. Wilson called biophilia. Wilson defined biophilia as “the urge to affiliate with other forms of life” or “the connections that human beings subconsciously seek with the rest of life.”

Wilson, one of the most important scientists of the 20th century, was a naturalist from earliest childhood, and he never lost that childlike wonder in the midst of nature. He joined Harvard in 1951, and had to hold his ground against the prevalent idea that the only biology that mattered was molecular. Studying species and their relationships, according to men in their laboratories, had become a quaint hobby. Wilson knew better, and he prevailed, pushing the study of visible nature in new, brilliant, fascinating directions.

Along the way, though, he became haunted by the intensifying loss of species and ecosystems – entire landscapes, really – as human population, agriculture, forestry, and industry expanded at a thoughtless and exponential pace. “Destroying rainforest for economic gain,” Wilson once said, “is like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal.”

In Wilson’s lifetime, population nearly quadrupled, from 2 billion in 1929 to 7.9 billion. The start of his career coincided with the beginning of what ecologists have called the Great Acceleration, when human impacts on the web of life shifted from astonishing and bizarre to catastrophic on a geological scale.

In the face of the increased rate of extinctions and rapidly diminishing biodiversity, Wilson worked to remind us that our humanity is not defined by the consumption of industrial goods, televised/digital entertainment, and fossil fuels. Our urban/suburban/indoor lives are increasingly abstracted from the real world, but he knew that our evolution in the community of life still shows through us like houselights through shuttered windows.

This is perhaps most clear in his Biophilia Hypothesis, introduced in his 1984 book Biophilia, which explored in depth the evolutionary and psychological roots of our attraction to the natural environment. Simply put, one or two million years of our hard-fought and hard-earned evolution within the community of life will not be stifled by a few centuries of pretending that the natural world doesn’t matter.

This innate love of living things is woven through our lives – from pets and houseplants to bird-watching and stress-reducing walks in city parks – but it’s not simply a matter of appreciating nature like a painting. This is about hard-wired genetics, which play out equally in our love of a beautiful forest, our affection for baby meerkat photos, and our phobia of what my mother and sister might call “face-eating” spiders (which is pretty much any spider). The deprivation of children who suffer “nature deficit disorder” is as real as the joy, awe, and resilience they develop when spending hours outside.

When we explore and relax in the fabric woven by insects, grasses, animal tracks, birdsong, wind, pollen, amphibians, streams, spider webs, stones, and the architecture of trees and topography, and we are paying attention to the fabric’s details and breadth, we cannot help but feel the stirrings of our pre-Anthropocene lives. We might love it, we might have a million questions to ask of it, or we might feel the uncomfortable weight of the fabric on our urbane self-involvement, but the recognition of the real world is universal.

The living world is the real world, and the real world is full of “magic wells,” as Nobel Prize winner Karl von Frisch put it. Frisch won the Nobel for discovering the language hidden within the dance of honeybees, and he referred to his bees as a magic well because no matter how much he discovered, there was always more to learn. (For a recent dip into the honeybee well, I highly recommend My Garden of a Thousand Bees, a PBS Nature documentary shot lovingly in its filmmaker’s urban garden during the pandemic.)

Likewise, there’s a beautiful description of E.O. Wilson in the opening paragraph of a chapter (“The Biophilic Sublime”) devoted to him in Alan Gross’ 2018 book, The Scientific Sublime: Popular Science Unravels the Mysteries of the Universe. It follows an excerpt from a joyous letter written by Charles Darwin to his sister as he sat in a rainforest in Brazil: “Whilst seated on a tree, & eating my luncheon in the sublime solitude of the forest, the pleasure I experience is unspeakable… so that if I gain no other end I shall never want an object of employment & amusement for the rest of my life.” It’s the magic well again, where there is no end of joy and exploration. Gross writes that Wilson, sitting in the same rainforest where Darwin wrote his letter a century earlier,

shares the identical “cathedral feeling,” the identical sense of the biological sublime evoked by the diversity of the biosphere: “Hold[ing] still for long intervals to study a few centimeters of tree trunk or ground, [and] finding some new organism at each shift in focus.” It is a feeling for his fellow creatures exhibited in every aspect of E. O. Wilson’s life: his efforts to understand ant society, his discovery of sociobiology as means of understanding all societies, and, finally, his efforts to preserve the diversity of the biosphere in which all societies must find their place. For Wilson, environmental ethics flows naturally from the cathedral feeling he shares with Darwin, their sense of the biological sublime.

Wilson writes in Biophilia of his time in the Brazilian rainforest,

I opened logs and twigs like presents on Christmas morning, entranced by the endless variety of insects and other small creatures that scuttled away to safety. None of these organisms was repulsive to me; each was beautiful, with a name and special meaning.

Even in a world at war against the fabric of life, the magic wells are still everywhere. Darwin’s “unspeakable pleasure,” Wilson’s capacity to spend hours observing a handswidth of tropical life, von Frisch and the filmmaker spending months in their gardens of a thousand bees, and Kimmerer greeting the Heal-All in her path are all rational, ethical, loving responses to the animate world of which we are an integral part. These wonderful humans, and hundreds of millions less well known, are our guides to the magic wells, which are, of course, always open to us.

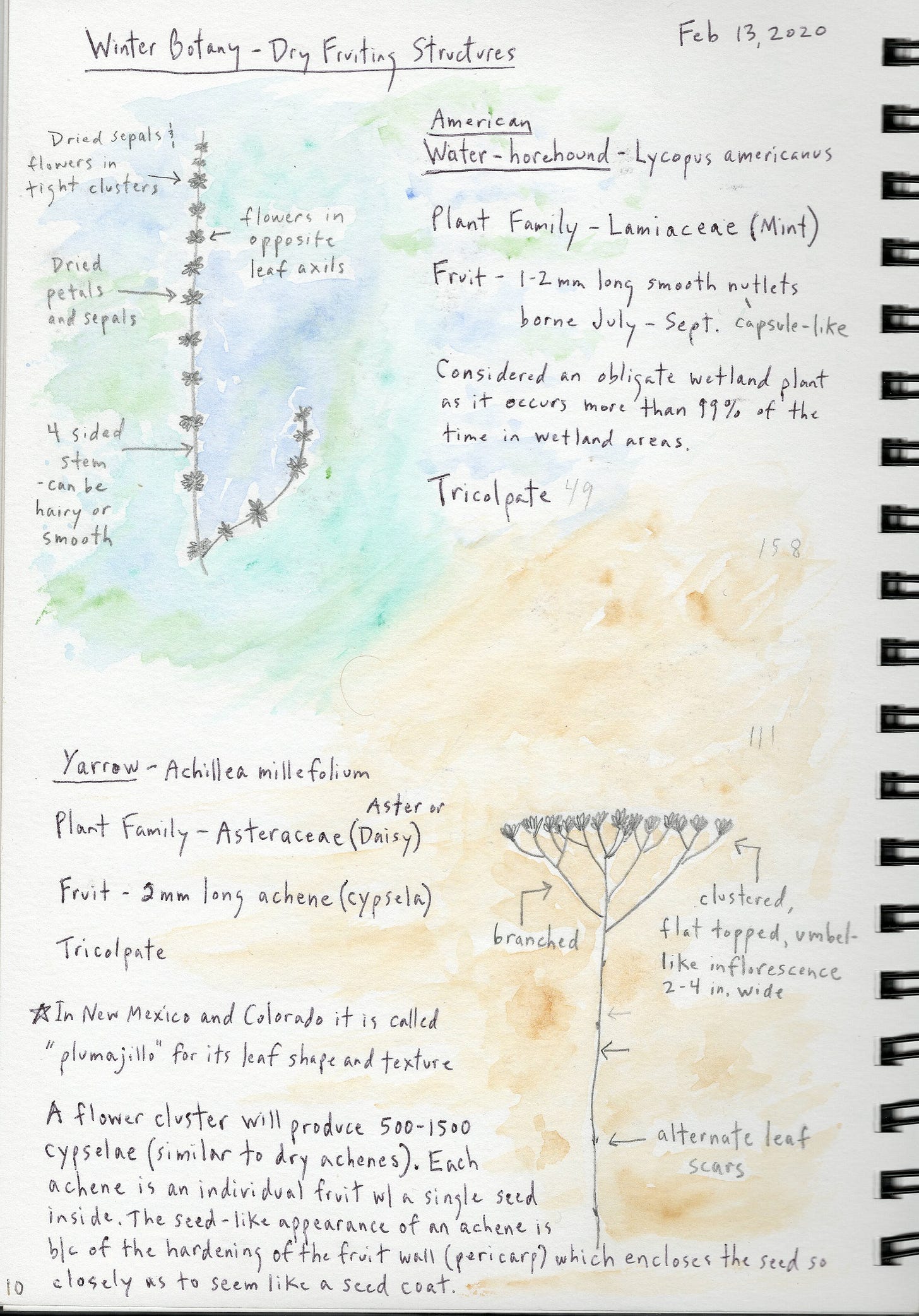

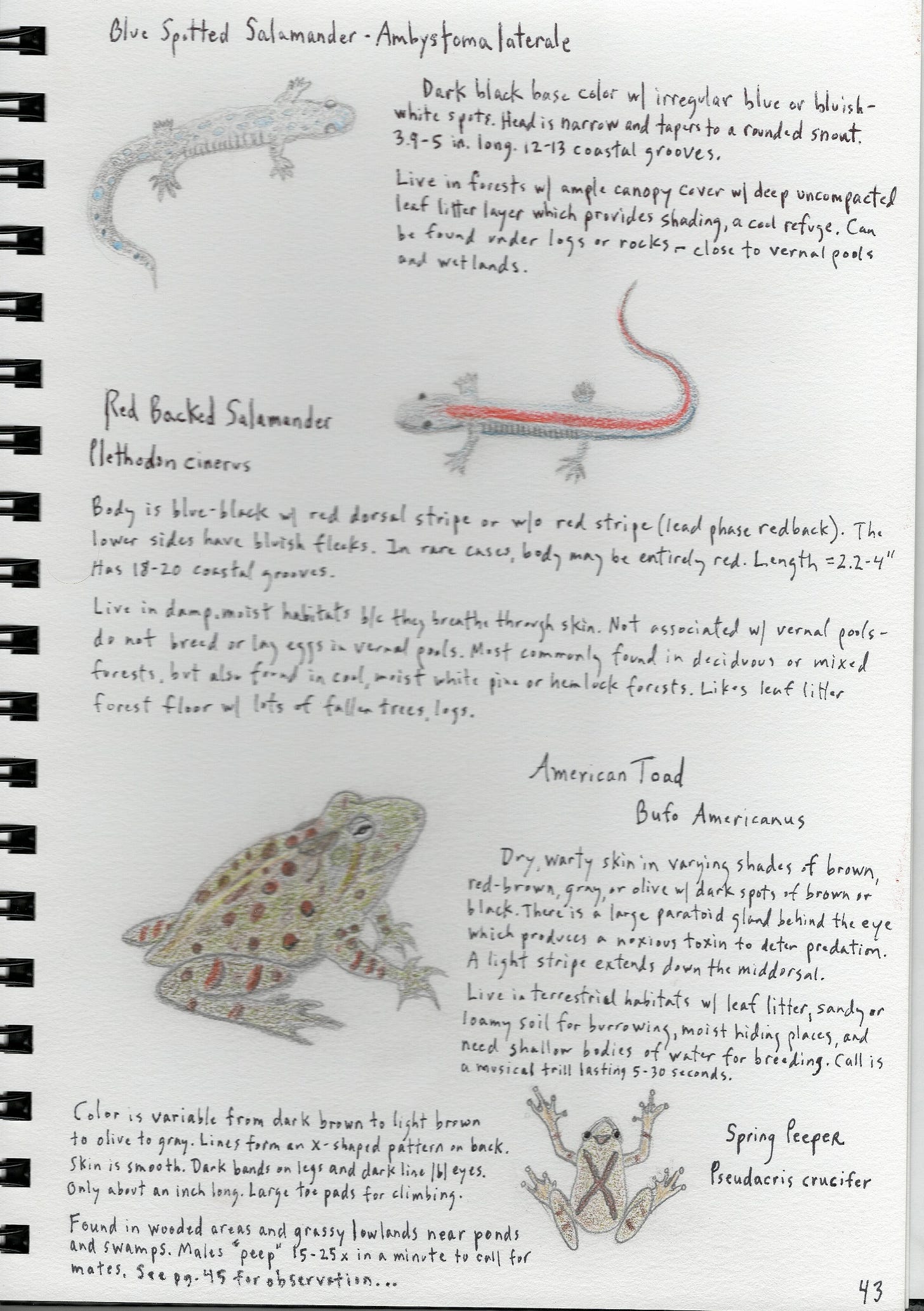

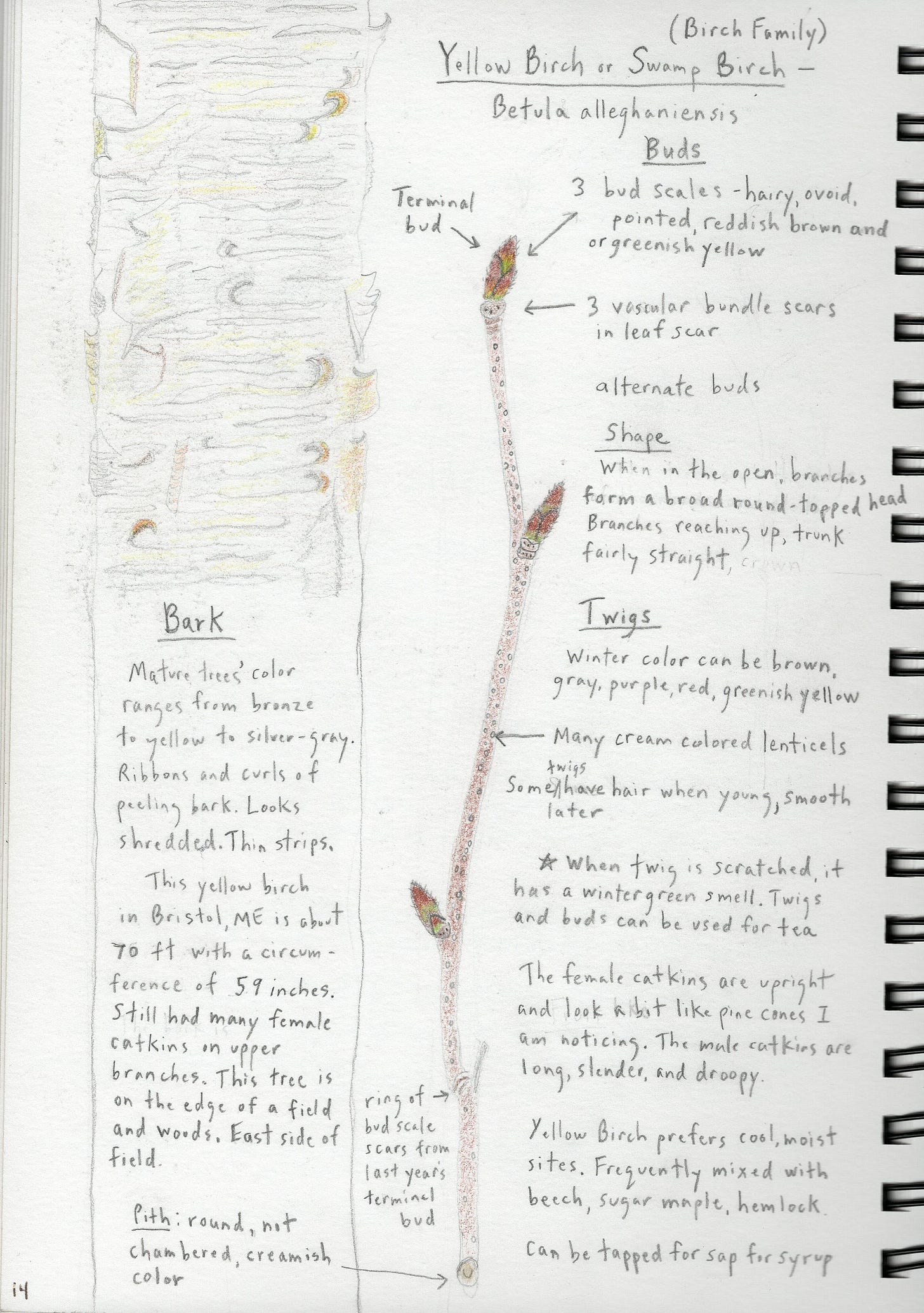

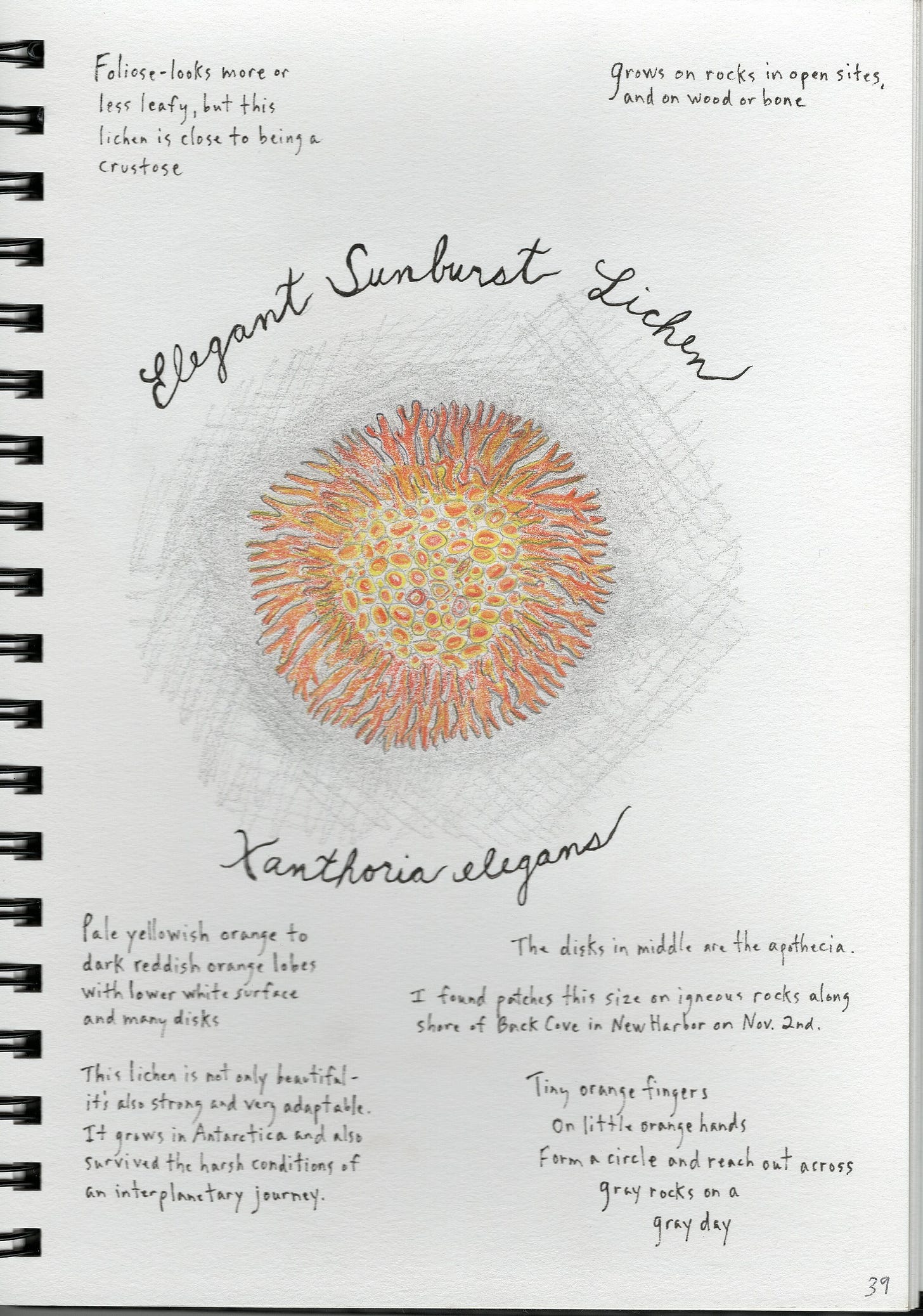

Speaking of wonderful humans, my wife Heather spent 2020 in the Maine Master Naturalist Program, an intensive introduction to the world outside our door here, and as part of her studies filled notebooks with the observations and illustrations you see here. Since that time, she and I have embarked on journeys of understanding that will continue throughout our lives, finding entertainment, mystery, awe, and joy as we study the hidden world of lichens and mosses, the vast world of insects, and the interconnected world of forests. And so much more, as you can see from Heather’s notebooks.

Part of the genius of the MMNP, too, is that graduates are expected to teach what they learn, as volunteers, in their communities for years to come. The goal, as Heather says, is to help others to connect and feel the love that Kimmerer talks about.

That’s biophilia broadened by empathy into a cure for Anthropocene suffering.

I’ve written so far, mostly, of the love that zooms in on the details of life – the child with the ladybug, the naturalist with a loupe – which is our biophilia expressed through careful study of the meaningful lives led by other species. Let’s broaden the picture for a moment to contemplate the ideas of topophilia and ecophilia. Ecophilia, the love of our home habitat, can serve as a synonym for biophilia, but I like it instead as an umbrella term for the combination of topophilia and biophilia.

Topophilia is the love of place. The term has its origin in a mix of poetics and human geography, but the idea is simple enough, especially if you overlap it with biophilia: we are biologically driven to develop what we think of as our cultural attachment to place. Remember the childhood forest or family farm evaporated by heedless development? Is our attachment and subsequent suffering merely personal? Or is it that our ancient genes compel us to see, per Shakespeare, “books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything?”

For me, the idea of topophilia immediately draws up very strong feelings for three different places: Maine, Antarctica, and New Zealand. Midcoast Maine is my birthplace and home ground, and when I return after being away for too long the sulfurous smell of low tide hits my brain like a perfect piece of chocolate cake. I can feel my body settle happily into itself.

At age 27, I fell deeply in love with Antarctica, a landscape so otherworldly that to love it is to be haunted by it. I worked there for most of a decade, and the feeling only grew stronger. Even today, 20 years since I last stepped foot there, memories and images of the ice pull at me with their own lunar gravity.

And finally, there’s the place that served as the middle ground between Maine and Antarctica for that decade: the South Island of New Zealand. I spent a couple months, year after year, hiking and exploring, breathing in the air of mountains and rainforests and wild, rugged shorelines. Yes, it’s one of the easiest places in the world to fall in love with, but for a decade it was a second home. I might have stayed forever but for the pull of family and the Maine coast.

All of which is to say that I, and you, have deeply-written code in our DNA that connects us to life on Earth and, more broadly, to its community landscapes. We’ve been finding meaning in the fabric of life for all but the last few moments of human history, so the revelation that awaits us now is in the remembering rather than the realizing. If we step off our daily roads and paths long enough and with enough intention, and allow ourselves to be embraced by the fullness of the natural world, the love, affection, tendency, desire, and attachment should well up somewhere within us. Whether we bathe in the ocean or a forest, there’s a depth we need as desperately as it needs us.

With love comes consequences. But the cure for suffering is more love for what we’re losing, and for what we’re afraid to lose.

I should close by saying that I’m not caught up with the use of these –philia words. It’s the love and its consequences that I’m after. If we feel and acknowledge the love, then we’re more likely to take action in the midst of the Anthropocene onslaught.

For what it’s worth, the words topophilia and ecophilia barely exist in the language. Even biophilia, if we were to stop people on the street and ask them if they knew the word, would scarcely register. And, to be honest, these –philia words are about as clunky as “Anthropocene.” The words aren’t the point so much as the underlying story about what it means to be human at this time on Earth. They all ask, or answer, the age-old questions: Who are we? What are we doing? What do we need to change?

The Anthropocene poses an unfathomable scale of threats to what we love. Worse, the rapid changes can make it harder to develop and feel that love, as we face the challenges of rogue weather, intense heat, the uncertain future of millions of species, and an increased fear-driven push to stay indoors. But that’s for another day. For now, it’s about those questions – Who are we? What are we doing? What do we need to change? – and how time devoted to in the community of our fellow species can inform our answers.

The heal-all is love for the magic well, and the action that our love inspires us to take.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the BBC, stunning news from the abyss. Polymetallic nodules, which are millions of years old, lie on the deep sea floor and, as the only solid objects around, support the strange, largely-unknown array of abyssal life. New research indicates that the nodules actually produce oxygen! These nodules are rich in metals valuable for battery production for the clean energy transition, and they seem to be acting like batteries powering the splitting of H2O molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. As I wrote some time ago, the nodules and their habitats are threatened by corporate interests which hope to make billions of dollars from large-scale harvesting. This new research may help prevent that destruction.

From Volts, an excellent podcast interview on the terrible “bioenergy” wood pellet industry and its massive unnecessary harms to forests. I’ve known that the industry has been tearing down forests in the southeastern U.S. and selling pellets to Europe, but I didn’t know that “over half of what counts as renewable energy in the European Union is bioenergy, i.e., wood pellets burned for heat or electricity.” This is an industry that need to disappear under the rising tide of solar, wind, and other true renewables.

As a follow-up to the article I boosted last week on the USFWS proposal to slaughter hundreds of thousands of barred owls in a bid to save endangered spotted owls, here are three excellent sources for further understanding: From High Country News, an interview with two bioethicists; from Atmos, a personal essay on how barred owls should perhaps be seen not as an invasive species but as a climate migrant; and from Yale e360, a fuller explanation of the situation. Thanks to

and for the deeper dive.From the Times, the Biden administration has come out finally with a government-wide plan to phase out single-use plastics. This is very good news, and one more reason to ensure a continuation of Biden’s policies by electing Kamala Harris. The White House also has plans “to create a market for substitutes that are reusable, compostable or more easily recyclable, and to intensify regulations on plastics manufacturing.

From Grist, a profile of a Minnesota state senator working hard to return lands to the Indigenous nations who are their rightful owners.

Through co-managing or co-stewarding Minnesota will become a healthier place, a happier place, and a place where the racial tensions that have existed — that most people won’t acknowledge — become almost nonexistent.

Also from Grist, cities really should be shifting to cool roof technology. A new study finds that cool roofs are better for reducing urban heat than green roofs, solar panels, or increased streetside trees. The best policies will vary from city to city and utilize an all-of-the-above strategy. Cities will only become hotter and less livable, and the time to make changes was yesterday.

From Vox, an article explaining in no-nonsense terms that population decline is inevitable. Nations are all more or less on the same path, though several are still increasing rapidly. The latest UN estimate is that population will peak at 10.3 billion in 2084, just sixty years from now. Unfortunately, the Vox author dismisses the notion of overpopulation, and says nothing about the environmental consequences of our current population or of the many decades ahead before we begin to decline from today’s numbers.

From Berkeley Earth, the world is hot, hot, hot. Everything is off the charts, but if you like charts, this is an excellent source.

From Phys.org, a new study makes a good if disturbing argument that the rapid deoxygenation of bodies of water - from ponds to oceans - should be added to the list of planetary boundaries. Once fresh and salt bodies of water lose too much oxygen, the catastrophic impacts will spread throughout ecological and human communities. If the concept of planetary boundaries is new to you, start with an explanation from the Stockholm Resilience Centre. These boundaries represent objective planetary-scale thresholds for unacceptable human impacts on the living world. Of the nine already established, we’ve crossed six.

This article spoke to me, Jason. I have long used personal prounouns for non-human animals and I might extend it to other living things. Doing this, I found, makes us more connected to the natural world. Biophilia is a healthy response to us humans; we ought to love what sustains us.

And I am not being sentimental. I liked the notebook feel of your wife's work; there is a feeling of life within the pages. Please convey this to her.

I love (ha! but I do) seeing how widely Robin Wall Kimmerer inspires. And to add to these thoughts, Carl Jung said that the opposite of love is not hate, but power, and that there is love, there is no will to power; and where there is power, there cannot be love.