Hello everyone:

I’m enjoying revisiting essays from a few years ago, when the Field Guide was young and subscribers were few. This one has been fully rewritten and updated for a much larger crowd.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read a curated collection of Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

When I began writing this Field Guide over three years ago, I joined the global chorus of Cassandras. That is, I joined the growing network of people who can see that the difficult future awaiting much of life on Earth has already begun to arrive, who understand that human behavior is the cause, and who know that the worst of this future was (and still is) avoidable. (You are, I assume, part of the network too.) We are Cassandras because this “prophecy” has not been fully understood or embraced by a culture that cannot see that a decimated natural world is where our flourishing ends and our floundering begins.

As with so much of Greek mythology, there are very different versions of Cassandra’s story, but the heart of it for our purpose here is that she was a daughter of the king and queen of Troy, and so beautiful that the god Apollo fell in love with her. He offered Cassandra the gift of prophecy in exchange for her love. The gift was hers, but she could not (or would not, according to the playwright Aeschylus) return the affection.

An aggrieved Apollo could not undo the gift, so he poisoned it with the curse that Cassandra would never be believed, regardless of the truth of her words. (Apollo’s curse on Cassandra is the action of a psychopath, but it’s good storytelling; how interesting is a character who knows what will happen and convinces everyone every time?) Thereafter, her family and the Trojan people thought her a liar or insane.

In today’s global community of Cassandras I play a tiny role – turning phrases rather than saving forests or changing policy – but it’s still a task worth doing if it turns up the motivation dial a little. The larger community (what we call life) that has sustained us through our evolution desperately needs our awareness, attention, and action, and I’m happy to do what I can.

It’s been a bit of a journey to reach this Cassandra stage of my life. At age 19 I realized, much to my surprise, that I wanted to be a writer. I had taken a semester away from college to hike half of the Appalachian Trail. My interest was poetry then, not prose, but those were beautiful months of living both in the woods and in my head, and as I walked I also started on a path of writing at the intersection of consciousness and the natural world we have largely retreated from.

After grad school for poetry, I wandered off to Antarctica, where I shifted to lyrical prose that tried to inhabit a blank landscape which scarcely responded to language. A decade later, through a bit of luck, I ended up publishing an unusual narrative history of Antarctica that explored the human experience of the ice, cleverly disguised as a “culinary history” of a continent with no cuisine. But to write it I had to teach myself how to write regular narrative and push the poetry to the corners of my sentences. By then I had landed back here in Maine to reconnect, season by season, with my home landscape.

Then, several years ago, my family was stunned by a huge, foolish, unnecessary, ill-designed and ecologically harmful development next door to the farmhouse. What had been a large and quiet forest was being turned into 24 acres of parking lots for a popular botanical garden that suddenly had Disneyland ambitions and predatory management. (It’s a long story that I’ll write about sometime. I can tell you already that the essay will be titled “Down the Garden Path.”) My family and our allies fought a long, losing battle against lots of money, lawyers, and public opinion in a small town that had mistaken a golden calf for a golden goose.

That process was very bruising for many reasons, but one of my realizations after three years of fighting was that if even a “green” organization in a nature-loving state could be so blind as to unapologetically wipe out a large swath of habitat crucial to half a dozen wetlands, and to increase the risk of nutrient overload for the town water supply, then there was a lot of work to be done to articulate the basics of the Anthropocene. I was haunted also by the disinterested silence in town meetings that greeted what I knew to be clear statements of the science and the ethics. We had become Cassandras, and it wasn’t a good feeling.

I decided, by starting the Field Guide, to embrace the role.

Not that our tiny saga compares to the catalogue of wretched misery that was Cassandra’s life after Apollo’s curse: the slaughter of Troy and her family, rape, captive mistress to Agamemnon, and finally her murder by his wife, all while knowing much of what would happen. The power of her story is in that tragic combination of deep insight and deeper helplessness amidst horrors.

It is, of course, a tragedy that in various iterations has befallen countless women throughout history, women who spoke truth to power or, more often, who simply fell victim to men’s rules, men’s wars, men’s rage, a community’s deafness, or a nation’s fear. Here in the early Anthropocene much of this is still happening, though a silver lining on the decline of life on Earth has been a simultaneous moderate improvement in the fate of women and girls. Looking ahead, this is important because if we can continue and accelerate those social trends – universal access to education, financial investment, family planning, etc. – we can also blunt the worst Anthropocene impacts.

For now, at least, we live in a world in which hundreds of millions of people can hear young Greta Thunberg accurately critique the weak COP 26 pledges of carbon-neutrality as “blah, blah, blah.” Women lead nations, government ministries, scientific studies, NGOs, protests, community groups. Women write the books and gather the data.

I recommend an excellent Reuters long-form profile, “The Cassandra,” of Australian climatologist Julie Arblaster. At the start of the austral summer in late 2019, her analysis of weather patterns around Antarctica led her to predict a high risk of a bad fire season in Australia, a country whose government had been far more interested in selling coal than listening to the scientists. Within a few weeks, despite government dismissal of the threat, the country was ablaze.

The profile is fascinating, providing a private portrait within the grand public discussion about the fate of the planet. Arblaster was reluctant to speak publicly, self-censoring in part because of her shy nature and in part because of how tough the Australian government had been on climate Cassandras.

This piece is part of a six-part series based on the Reuters Hot List of the 1000 “most influential” climate scientists, only one in seven of which are women, highlighting the slow-to-close gender gap in academics and science. As a bit of a historical follow-up, you might read Paul Krugman’s 2009 op-ed in the Times titled “Cassandras of Climate.”

And then there’s the recent film Don't Look Up, starring Jennifer Lawrence and Leonardo DiCaprio as ordinary, in-the-trenches astrophysicists who find a planet-killing asteroid is headed our way. In a darkly funny and depressingly relevant dramedy, they become asteroid Cassandras struggling to get their message out in a hypermediated world glutted with information but starved of truth. The story serves as an analogy for the fight to bring the climate battle to the center of political and public attention, of course, but it’s also a proxy for the larger problem of putting science – not just technology – at the heart of culture.

The movie suggests another reading of Apollo’s curse. It’s not necessarily that Cassandra isn’t believed, but that no matter how accurately she divines a tragic future nothing will be done to avoid it. People might understand or even agree with her, but fail to act. This interpretation is both spookier and more relevant to our time, because it speaks to apathy rather than antipathy.

Only 37% of Americans, for example, say that the rapid heating of the Earth is extremely or very important to them personally, though 72% believe it’s happening. Cassandra might feel Apollo’s cruelty when an audience consistently assumes she’s crazy, but if people understand but refuse to show concern? That’s a curse.

I’ve read that in Aeschylus’ play Agamemnon, Cassandra is depicted as having retreated into a despair that resembles madness and that even the chorus – which in these ancient Greek plays is meant to narrate and comment on the action – could not understand her story. She stands alone onstage, silent and ignored, before speaking of her fate in a “mad scene” which falls on deaf ears. Now alone in the world, a victim of Apollo’s malice, she moves offstage to the death she knows is coming at the hand of Clytemnestra.

It’s worth remembering that to qualify as a Cassandra – the voice with a stark prophetic warning – we must be speaking the truth. Otherwise, we’re merely offering fears, guesses, or conspiracies. Prophecy is a rare commodity, after all.

That said, there’s plenty of easy truth-telling for us to do. The more experience we have, the better we can see around the corner. When a drunk veers toward the pond, for example, or the George W. Bush administration veers toward Iraq in an illegitimate and half-witted geopolitical ploy to control the Middle East, we can be horrified at the obvious mistake, or say, with Gene Wilder’s mock concern in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, “Stop. Don’t. Come back,” because we know it’s too late.

For the climate and biodiversity crises, the truth is also pretty straightforward. We’re seeing it play out daily. The benefit, if we can call it that, of the decades-long misinformation and disinformation campaigns by the fossil fuel industry and its allies against climate science and basic ecology is that the data and the models and the analysis are now ridiculously strong. It’s beyond sad that two generations of scientists and activists have had to grovel, Cassandra-like, in the court of public opinion while simultaneously developing incredibly robust science that the public still scarcely acknowledges or understands.

But here we are at this point in history, where the prophecy is irrefutable. We’re bearing witness to ocean acidification, intensified chaos in storm systems, a thousand-fold increase in the extinction rate, Arctic permafrost thawing, the destabilizing of Antarctic ice shelves, the rapid depletion of life in the world’s remaining coral reefs and tropical forests, and so much more.

The basic outline of all these observations was available decades ago. We don’t know exactly how things will play out, given variables like undefined ecological tipping points or the possibility of effective large-scale human action, but Cassandra didn’t know all the details of the Trojan War either, only that if her brother Paris went to Sparta to carry off Helen, the war and Troy’s destruction were inevitable. As Alan AtKisson wrote about our environmental dilemma in Believing Cassandra: An Optimist Looks at a Pessimist's World,

Too often we watch helplessly, as Cassandra did, while the soldiers emerge from the Trojan horse just as foreseen and wreak their predicted havoc. Worse, Cassandra's dilemma has seemed to grow more inescapable even as the chorus of Cassandras has grown larger.

Yet there are victories everywhere for the Cassandras of climate and ecology. Look no further than

’s Global Nature Beat for the most comprehensive and fascinating weekly round-up of biodiversity news anywhere. It’s amazing, and amazingly useful if you need to know how much great work is being done, or at least attempted, at the global, regional, national, and local scales.Not a lot of the news there is good, of course, and much of the good news is still promissory and slow, like the IPCC and COPs for climate, and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the 30x30 push (to preserve 30% of Earth by 2030) for biodiversity. Even the incredibly rapid progress in transforming the energy economy away from coal and gas is conditioned by the fact that fossil fuel use isn’t yet decreasing, but the map to a better world is being drawn.

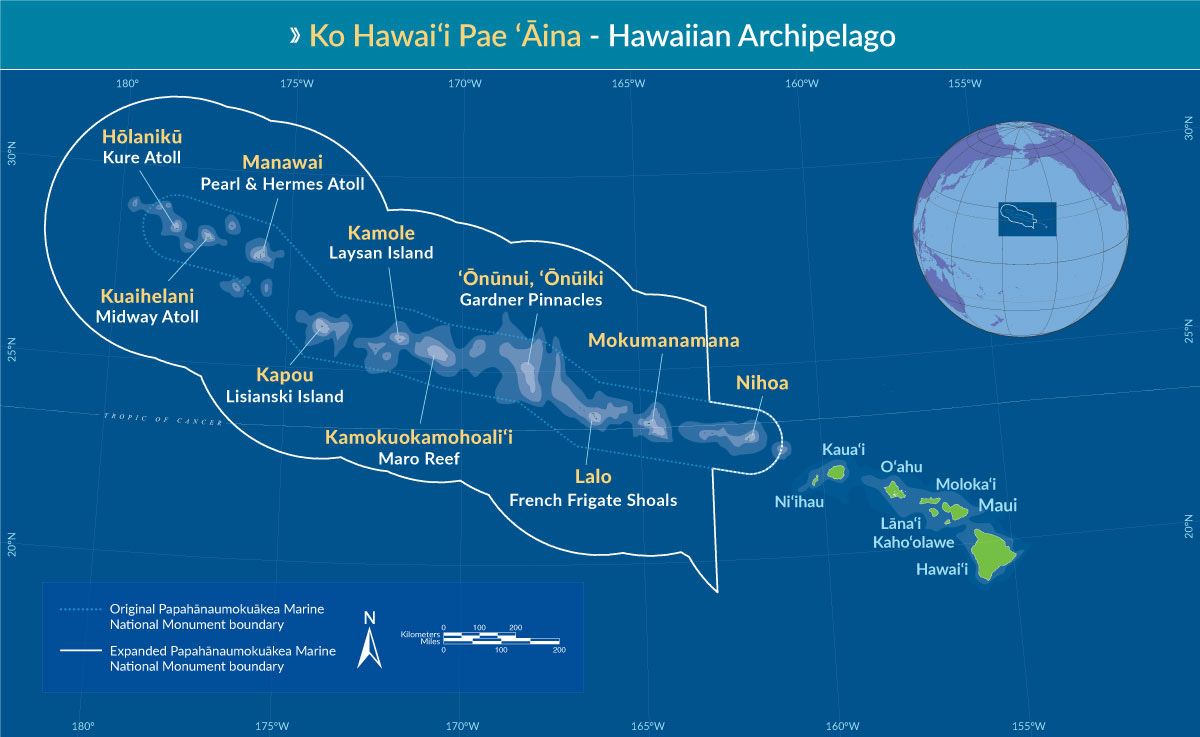

But many of the wins are momentous: Some are single events, like the creation of the massive Ross Sea Marine Protected Area in Antarctic waters and the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the Pacific. Some are positive tipping points, like China’s transformation of the solar and EV industries and the Biden administration’s multifaceted efforts to irrevocably reshape the U.S. economy around sustainable energy.

Perhaps the greatest achievement and the greatest promise, though, is in the growing network of Cassandras behind all of this transformation. From the scientists, indigenous activists, environmental groups, academics, and government officials who spend every day pushing the slow barge of civilization in a better direction, to the voters, protesters, naturalists, teachers, writers, artists, and local organizers who remind policy-makers what we actually want, the chorus is larger and more forceful every year.

And that’s the point. That’s how we rescue Cassandra from her fate. When the audience chooses to become Cassandras too – practicing the ecological ethics, learning the science, and echoing the call – then the road toward no Cassandras opens wider. The mortals finally see through Apollo’s selfish machinations. The stark prophecy becomes common knowledge, and the work to avoid the worst of it becomes the task at hand.

And really, when we look at how we got to this planet-harming threshold, the truth is that there never was a curse. There has only been opposition with vested interests. There have been spineless politics and shameless profiteering at every scale. There have been counterfeit Apollos, men reeking of burnt oil pretending to be gods of the Sun.

Which means, in a sense, that we have never been Cassandras. We have only been the usual victims of the games the wealthy and powerful play atop the lives of the human community and the community of life. Which reminds us that solving these crises is largely a social problem with social and political solutions. We don’t need to convince everyone we’re not crazy. We only need to remind everyone that a better world is available if we’re willing to do the work.

As Arundhati Roy, the great writer and activist, put it, “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.” When she arrives is up to us.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In curated Anthropocene news:

For further reading at the nexus of Greek mythology and women singing about the wounded world, I recommend two excellent books by friends of mine: Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung is a brilliant reimagining of Ovid’s Metamorphoses by Nina MacLaughlin, each short myth rewritten from the perspective of its previously voiceless female characters, and American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life is Jennifer Lunden’s excellent, groundbreaking memoir and deeply-researched history of industrial capitalism’s impact on our bodies which, unsurprisingly, have suffered in parallel with the Earth. American Breakdown is “a Silent Spring for the human body.”

For a fascinating visualization of the relationship between the human-built world and the natural world, check out Biocubes.net. The stuff we’ve made, from cars to concrete, now outweighs all of life on Earth. This is shocking once you realize just how minuscule we humans are, even with our 8 billion population, in the scheme of things. Our livestock have double the mass we do, but the buildings and plastics and roads, etc., are so massive that they outweigh all the plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria on the planet. Biocubes is a short and clever step-by-step visualization that will help you see the scale of what we’ve done.

From Inside Climate News, the incredible successes of the rights of nature movement in Ecuador - most notably enshrining those rights in its constitution - are still accompanied by challenges, like enforcing court rulings that protect the right of, say, a river or frog species to thrive. But the rights of nature movement is spreading, and this article uses Ecuador’s example to point out what’s next.

From the Guardian, more sustainable chocolate may be on the way. A new technique which uses the pulp and husk of the cocoa pod, rather than just the beans, has been developed. The pod and husk are mashed to make a sugar substitute, making chocolate more nutritious and making cocoa growing more efficient in its use of water and land.

More good news from the Guardian: A story of a massive UK estate where unprofitable intensive agriculture was given up and replaced with an incredibly successful rewilding program. A film, Wilding, will come out next week.

From Yale e360, two difficult wildlife stories: the rapid spread of chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer and other animal populations poses a terrifying long-term threat to both wildlife and human safety, and the disgusting tradition of rattlesnake round-ups is fading but still kills and torments thousands of snakes every year.

From Grist, the important difference between Indigenous peoples being invited to co-steward rather than co-manage protected land. Stewarding is advisory, but managing - which native peoples have been doing for millennia - is the real deal.

From NOAA, the Biden administration has announced $278 million in funding for fish passage projects around the U.S. in both state and tribal-controlled areas. This is excellent news for long-term fish conservation.

From Hakai, an excerpt of a new book on the huge but under-reported problem of anthropogenic noise in the oceans. We make a constant deafening cacophony with our ships, sonar, drilling, and much more, and it severely impacts much of ocean life. (You can also check out my three-part series, “Quieting the Anthropocene Seas.”)

From Axios, UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called for a ban on advertising for fossil fuel companies. He accuses advertising firms of helping the companies “shamelessly greenwash” their crimes against the planet, and suggests governments treat fossil fuels as we do tobacco: a health hazard that deserves no public encouragement.

From the Revelator, the complex negotiations being done to protect what we can of the wetlands and their species in the Klamath Basin Wildlife Refuges. Drought has made uneasy allies of agriculture, tribes, and refuge managers.

Even if we all become Cassandras will it be enough? I hope so.

Very large forces are now in train and what took decades to start rolling may take decades to slow back down and reverse. It's going to be a gigantic multi-pronged ensemble effort- the greatest sustained and planned effort our species has ever attempted. But we can do it. the question is will we?

I identify with Cassandra so I greatly appreciated this informative and inspiring read.