Affection for the Atmosphere

9/7/23 – An ode to the sky

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

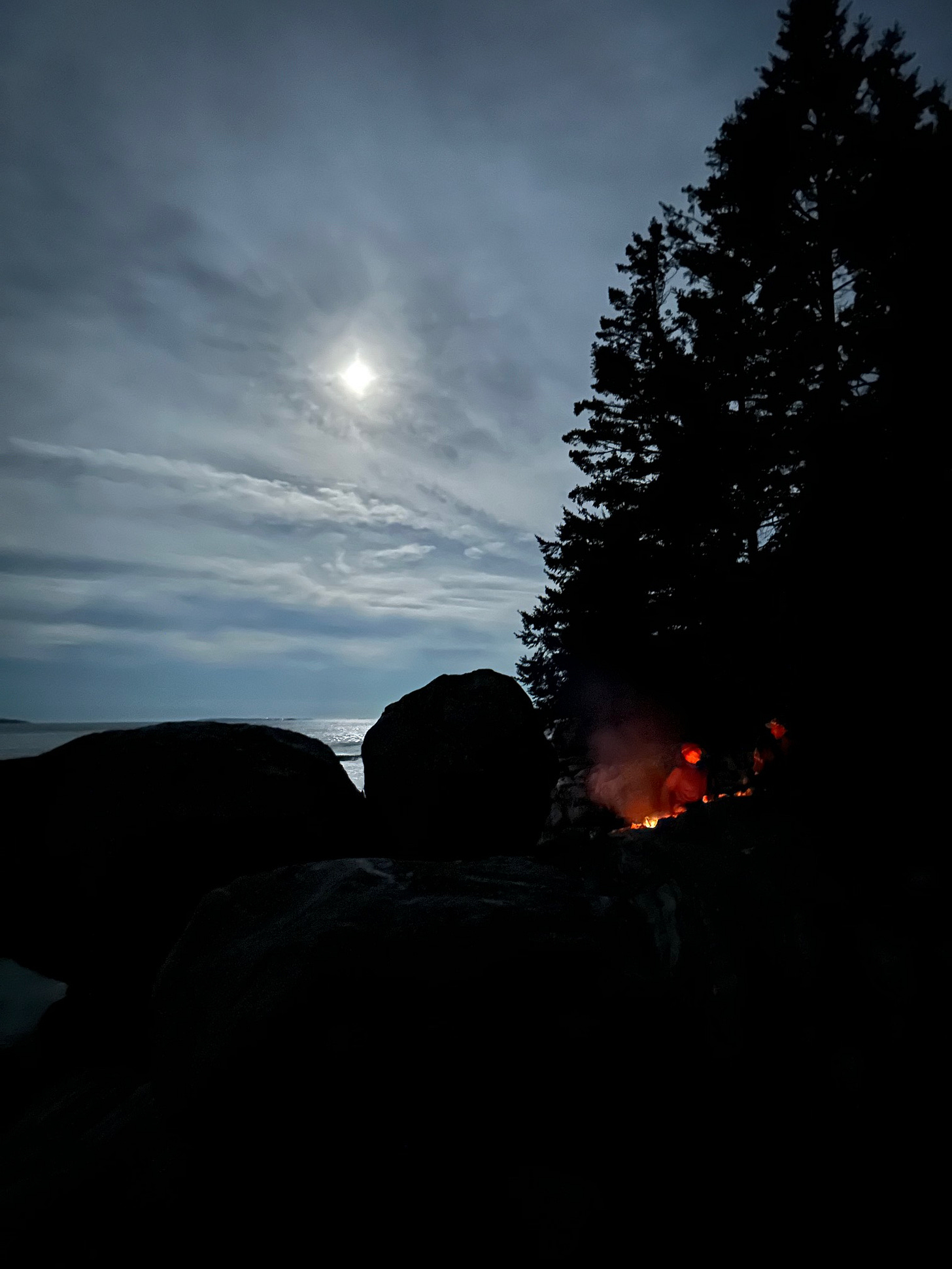

We finished our canoe trip on Muscongus Bay in torrential rain, rain so intense that a thought kept nagging at me: Maybe I have a leak in the boat? As we made the final half-mile crossing to the harbor, I had a choice: paddle or bail. Paddling without bailing meant the boat quickly became unwieldy with the weight of water sloshing around, but bailing only kept pace with the rain, which left Nell, my niece and bow paddler, wondering why she was doing all the work. So we sloshed some, I bailed some, and we made our way home through the torrent.

It was really, really lovely. Each time I looked over at Julian and Rebecca in the other canoe they looked supremely happy, flashing huge beatific smiles at the beautiful pattern the heavy rain was making on a flat, calm, windless sea. I might have chalked this up to some kind of rain-fever that infects residents of sunny, dry southern California… but I felt the same way. Despite the sloshing, and despite the steady trickle of water running down our arms under our raincoat sleeves every time we lifted our paddles, the rain was beautiful.

As I noted in my recent piece, “Reimagining Rain,” the rhythm of rain is the rhythm of existence: random but musical, beautiful but strange, steady and eternal. Imagine a faultless sea surface with just the slightest of swells breathing through it. Now imagine that surface pocked every few inches by a deluge of huge raindrops, each plunging through the water’s skin, creating a momentary rebounding spike of water a few inches tall capped with white.

We were motes inside an atmospheric fabric that stretched up to the clouds, a distance blurred by the dense tentacles of rain and a mist that permeated all of it. Down at water level, around the canoes, I felt like we were witnesses to a rarely-seen pattern of existence, like suddenly seeing the Earth’s magnetic field or an x-ray of life beneath the soil.

I’m tempted to say that the sky is always beautiful, day or night, but I’ve seen enough hot, humid, hazy days under a pitiless bland blue ceiling to hedge my affection for the atmosphere. I’m sure, too, that plenty of you have been oppressed at length by skies too dry or stormy to feel unconditional love for the air that weighs upon us and defines our daily experience of the planet.

And yet, even if we don’t always find the sky beautiful, we have to acknowledge that it is a thing of beauty.

This came to mind when, thanks to a recent

post by Rod MacIver at , I was reacquainted with the writing of Lewis Thomas. Thomas was a physician and medical researcher, but also a wonderful essayist with a poet’s voice. His 1974 book, The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher, was given the rare honor of National Book Awards in two categories: Arts and Letters, and The Sciences. I’ve been peripherally aware of Thomas’ literary science writing for years, but never picked up either The Lives of a Cell or The Medusa and the Snail. I wish I had.Thomas’ writing is astonishing, elegant, and persuasive. It is formal and casual all at once. He is effortlessly serious and light-hearted at the same time, and loads his sentences with scientific information that somehow floats gently into a reader’s consciousness. Here’s part of the sample from Lives of a Cell, talking about the photosynthetic creation of Earth’s oxygen-rich sky, that recently won me over:

It is hard to feel affection for something as totally impersonal as the atmosphere, and yet there it is, as much a part and product of life as wine or bread. Taken all in all, the sky is a miraculous achievement. It works and for what it is designed to accomplish it is as infallible as anything in nature. I doubt whether any of us could think of a way to improve on it, beyond maybe shifting a local cloud from here to there on occasion. The word "chance" does not serve to account well for structures of such magnificence. There may have been elements of luck in the emergence of chloroplasts, but once these things were on the scene, the evolution of the sky became absolutely ordained. Chance suggests alternatives, other possibilities, different solutions. This may be true for gills and swim bladders and forebrains, matters of detail, but not for the sky. There was simply no other way to go.

We should credit it for what it is: for sheer size and perfection of function, it is far and away the grandest product of collaboration in all of nature.

I love the light humor – “shifting a local cloud” – keeping company with a discusson of determinism in swim bladders and forebrains. And I love his quiet reinforcing here of one of his principal ideas: all of nature is interrelated, collaborative, woven. You can see why the National Book Award judges were helpless to choose between art and science categories in praising the quality of his writing. It’s a mark of Thomas’ unicorn status as a writer that these brief essays were first published in the New England Journal of Medicine between 1971 and 1973, before the book went on to sell millions of copies to the wider public.

The “cell” in Thomas’ book title, by the way, is not a liver cell or bacterium. It is the Earth, in metaphor, and the atmosphere is “The World’s Biggest Membrane,” which is the title of the book’s final essay. Viewed from the moon (“dead as an old bone”), the planet “has the organized, self-contained look of a live creature, full of information, marvelously skilled in handling the sun,” and it’s the membrane of sky that allows life to thrive. In the essay’s ten short paragraphs, Thomas cheerfully and eloquently lays out the relationship between the atmosphere and evolution. Here he is explaining the membrane metaphor in language both precise and familiar:

It takes a membrane to make sense out of disorder in biology. You have to be able to catch energy and hold it, storing precisely the needed amount and releasing it in measured shares. A cell does this, and so do the organelles inside. Each assemblage is poised in the flow of solar energy, tapping off energy from metabolic surrogates of the sun. To stay alive, you have to be able to hold out against equilibrium, maintain imbalance, bank against entropy, and you can only transact this business with membranes in our kind of world. When the earth came alive it began constructing its own membrane, for the general purpose of editing the sun.

So much meaning is wrapped up in that final phrase, “editing the sun.” All of life, the living planet, is a battery of sorts, borrowing from the sun to convert light and matter into consciousness and community, a bit of music and dancing in the cold warehouse of space.

Thomas writes very much from an ecological sensibility. “Every creature,” he writes, “is, in some sense, connected to and dependent on the rest.” That said, the word “ecology” appears only twice in Lives of a Cell, most notably in the essay “Natural Man,” in which he wrestles briefly with the consequences of humans becoming the dominant biological force on the planet. Thomas is, as a rule, a gentle writer. But he is an honest one too: “We haven't yet learned how to stay human when assembled in masses.” And this has ecological consequences:

It is a despairing prospect. Here we are, practically speaking twenty-first-century mankind, filled to exuberance with our new understanding of kinship to all the family of life, and here we are, still nineteenth-century man, walking boot-shod over the open face of nature, subjugating and civilizing it. And we cannot stop this controlling, unless we vanish under the hill ourselves. If there were such a thing as a world mind, it should crack over this.

If there were such a thing as a world mind… Such optimism in the 1970s. What would Thomas make of the internet, the first real attempt to cohere our global thoughts? I suppose he’d see it as we do, an amplifier of human nature rather than an answer to it. The next stab at a world mind will be the various AIs, approaching as I write this, built by corporations to further corporate thinking.

Unless there’s a rogue billionaire out there secretly working on an even more powerful AI that will think like a rainforest (and convince the others to do so too), I don’t think we should hold our breath hoping for a cohesive global recognition of the need to make peace with the community of life. But as Thomas points out, it is a daily heartbreak for the billions of us who feel kinship with the rest of life but hear our voices drowned out by the motors of Anthropocene culture. The task, as always, is for a sufficient mass of us to shout enough to shift policy.

There are more than a few notes of prophecy in Thomas’ writing that make it particularly relevant today. More than a decade before the “ozone hole” created by CFCs was discovered, and fifteen years before James Hansen gave his landmark testimony to Congress about the dangers of climate change, Thomas wrote this in his ode to the atmosphere (emphasis mine):

We are protected against lethal ultraviolet rays by a narrow rim of ozone, thirty miles out. We are safe, well ventilated, and incubated, provided we can avoid technologies that might fiddle with that ozone, or shift the levels of carbon dioxide. Oxygen is not a major worry for us, unless we let fly with enough nuclear explosives to kill off the green cells in the sea; if we do that, of course, we are in for strangling.

Remember that in the early 1970s per capita consumption was much lower and human population was 3.85 billion, less than half of today’s still-rising sea of human faces. The rate of population growth has been cut in half since then, but half the rate at twice the number means that we’re still increasing by roughly 80 million every year. That’s the current population of Germany.

What are the odds, in the impoverished world we’ve built atop the lush green worlds we’ve ruptured, that the 80 million last year, the 80 million this year, and the 80 million for each of the years to come (until population finally begins to shrink) will grow up to have more affection for the atmosphere than we do? It’s up to us to help them get there, through policy and elegant sentences and parenting with the awareness that the world they’re inheriting is, in most places, even poorer in remnant beauty than the one passed down to us.

As I wrote a couple weeks ago in “Between Islands,” if we each really understood the fragile miracle of the atmosphere, perhaps some affection would be more broadly felt:

As for the atmosphere, it’s only paper thin. Eight billion people are pumping out emissions from the burning of tens of millions of years of stored carbon-based fuel into the troposphere, which is only the lower 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) of the atmosphere. 7.5 miles is the distance from Wall Street to Harlem, or from my house to the nearest supermarket.

For a great illustration of how thin the troposphere is, check out the opening moments of the new climate TED talk from Al Gore. These first few miles of sky above us, he says, is being treated like an “open sewer” for emissions. Gore goes on to vigorously highlight the two main obstacles to cleaning up the sewer: intense fossil fuel industry opposition, and trillions in subsidies for the industry. He’s fired up, in fact. Well worth your time to watch.

Emissions are only half the story, however. At the same time we’ve intensified the atmospheric greenhouse effect with CO2, methane, and other gases, we’ve reduced the Earth’s forest cover by about half, and ravaged much of the world’s wetlands and grasslands. An Earth deprived of greenery moves less water between land and sky, and has less ability to moderate the water cycle, bringing more heat, droughts, and floods.

Knowing how fragile and galactically rare the atmosphere really is, perhaps it’s easier to find it as cute and sweet as a puppy…? I suppose not, since unlike most puppies the sky carries tornados and hurricanes. But still, there’s a necessary wisdom we need to share about this thing of beauty that shields us from the horror of a mostly dead universe.

Maybe, then, we need to tell each other anecdotes of our affection for the sky? I’ll start.

In the same way I wrote my two-part series, “Memoir in a Handful of Birds,” I could wax poetic for pages about skies I’ve known and loved. I remember, for example, hiking at treeline on the Appalachian Trail here in Maine amid clouds so dense that wisps of vapor sailed between my outstretched fingers. I remember twelve days of unbroken perfect blue sky hovering over the Antarctic campsite that Julian (yes, the guy in the other canoe) and I were struggling to keep together as katabatic winds, stronger every day, raced down the glacier like a mad invisible river. I remember Julian and I finding a softball-sized meteorite on the glacier and imagining its billions of years wandering the solar system before making a flaming passage through our atmosphere into a bed of ice. I remember staring out the window of a LC-130 for hours while flying over the East Antarctic ice cap, and loving its resemblance to the upper surface of clouds we fly over here in the warm world. And I remember a rainless Hurricane Bob sweeping across Cape Cod in September and burning all the vegetation with salt spray; leaves browned and fell, but then everything bloomed again, as if autumn were the new spring.

Lewis Thomas notes in “The World’s Biggest Membrane,” finally, that the atmosphere provides another service we rarely express gratitude for. Millions of meteorites falling every day would turn the planet into “the pounded powder of the moon,” he writes, if not for the bright, living shield of the sky. And even though we can’t hear that shield burning up those meteorites, “there is comfort in knowing that the sound is there overhead, like the random noise of rain on the roof at night.”

As much as Nell, Julian, Rebecca, and I loved the experience of paddling through the rain, we were grateful for the roof over our head that night, and for dry, comfy beds. Somehow, in this culture that’s burning through the community of life, we need to learn to feel equally grateful for both sky and roof.

Stories help, since humans seem to have evolved to store sunlight in our bodies primarily so we can tell each other stories. But we can start with joy too. If we can feel joy in the rain, then perhaps we’ll remember to protect the miracle it comes from.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Grist, the latest update on all the free money coming soon for the electrification of your home and transportation. In my post, “Electric Victory Gardens,” I wrote in detail about the opportunities (from the Inflation Reduction Act) for Americans to benefit from rebates and tax breaks for heat pumps and much more. I’ll update that as we get close to the funds becoming available. For now, here’s a quick reminder from this Grist article:

The rebates also are larger for low-income households. On the electrification front, the guidelines call for up to $8,000 for heat pumps, $840 for induction stoves, and $4,000 to upgrade an electric panel, among other incentives.

From Wired, an excellent long-form piece on the development of AI to help us begin conversations with whales. This is, in turn, part of a much grander adventure spearheaded by the Earth Species Project, which is working to use AI to help us, a few decades from now, understand and communicate with many species. The dialogue might help us develop the kind of global empathy necessary to prevent millions of plant and animal species from disappearing:

The idea of “decoding” animal communication is bold, maybe unbelievable, but a time of crisis calls for bold and unbelievable measures. Everywhere that humans are, which is everywhere, animals are vanishing. Wildlife populations across the planet have dropped an average of nearly 70 percent in the past 50 years, according to one estimate—and that’s just the portion of the crisis that scientists have measured.

From the Overpopulation Project, an excellent essay by Philip Cafaro titled “Procreation and Consumption in the Real World,” which very clearly lays out the argument for responsibly diminishing both as part of the necessary work of downsizing the human economy that is disrupting and diminishing life on Earth.

From Reasons to be Cheerful, talking to indigenous communities about their ecological grief is helpful. Peoples evicted from their lands in the name of conservation, or who see the community of life changing in a warmer climate, need to tell their stories to create some healing for them and to help prevent such trauma in the future.

From OneZoom, a mesmerizing website for exploring the tree of life. It’s a bit confusing at first, but I think the best way to start is to usethe search box in the top right corner of the site. Type in any species that interests you. A new tab will open with the selected species highlighted on its twig of the tree of life. The mesmerizing part comes when you slowly scroll outward and watch the seemingly endless fractal pattern of life emerging. It’s nice, for example, to see the tiny space occupied by humans and the other apes in a map of life that reveals the planet has never really been ours.

From Yale e360, another dubious tale of carbon credits and greed, this time about a Dubai sheikh and his company, Blue Carbon, working quickly to establish long-term deals with forested African nations to sell carbon credits for “forest conservation,” even though 1) the company has no experience with conservation, 2) the forests in many cases are not likely to need protection, 3) the local communities who live with and within the forests are not being consulted. In reality, the deals are a crooked win-win for politicians looking to enrich themselves and nations (to whom Blue Carbon will sell the credits) to claim a decrease in national emissions without actually lowering their emissions.

From the Times, an announcement from the EPA that, in accordance with an astonishing dumb and ecocidal ruling from the Supreme Court, the agency is eliminating protections for millions of acres of U.S. wetlands. If state and federal policy makers don’t provide those protections in law soon, the losses could be dramatic.

From Heron Dance, “What Does it Mean to Respect Life?”, another recent

from Rod MacIver that offers his usual lovely mix of quotations from literature and from interviews he’s done over the years with thinkers, philosophers, ramblers, and more. These Pause for Beauty posts are beautiful and well worth your time (and subscription).From the Times, the H5N1 avian influenza strain has killed tens of millions of birds around the world over the last few years, and may now be poised to leap from South America to Antarctica, where bird and seal species are densely populated and have no experience with such an outbreak. The results could be especially devastating.

What can one say? Another great essay from one of Substack's most lyrical writers. But it is not eloquence for eloquence's sake. It is an eloquence tempered with scientific analysis. Dispair and joy and sober reckoning. Not unlike Lewis Thomas in fact.... I purchased Lives of a Cell hardbound when it first came out and must say it provided so many insights that I still take energy from..a book both informative and transformative.

Amazing, just the other day, before this post, somehow somewhere from the ether it occurred to me that I had never read The Medusa and the Snail. (We must be channeling one another through the interwebs or the great unknown.) In that book, I now have yet another thing to look forward to (like every one of your posts)!