The Undercurrent

4/13/23 – Recognizing the scale of the problem

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I began writing the Field Guide two years ago, on Earth Day, 2021, to start a conversation about life, how we think about it, and the consequences of that thinking. By “life” I mean both our own existence and the beautiful, vibrant fabric of reality that still somehow nurtures us. But by “consequences” I don’t mean merely the distancing of our sense of self from plants and animals, nor do I mean only our profit- and population-driven destruction of ecology.

What haunted me then, and haunts me still, is the scale of the problem, the speed of its arrival, and how little attention it gets in daily life. It is a bizarre experience to observe our severe disruption of Earth’s basic planetary-scale functions – weather and climate, terrestrial and marine biology, atmospheric and oceanic chemistry, even sedimentary geology – and feel that very few people are noticing the full scale of it.

Thanks to scientists and activists, the world has woken to the global existential threat of climate change, and anyone dedicating their life to reducing that crisis is making a necessary, rational, and heroic decision, but climate chaos is only part of the story. My fear (on less optimistic days) has been that, without a common and shared ecological view of our full array of planetary-scale impacts, those of us fighting environmental battles are often just shoveling sand into an incoming tide.

Any writer, of course, hopes to move people to see the world as they do, and of course our communities have long been full of good, brilliant souls helping to push society in better, more sustainable directions. And, to be honest, before the Field Guide I wasn’t any kind of Cassandra because I wasn’t saying much. So to try to make things a wee bit better, I brought my muttering here to Substack, lengthened its sentences, and provided depth and context.

If I’m adding something to the discourse, it’s a bit of lyricism in the service of that planetary view, which includes wonder and grief as well as information. I talk about the beauty of the world and the threats to that beauty. I decided to build my writing around the idea of the Anthropocene, though it’s an awkward and problematic word. Maybe I should have called it the Field Guide to a New Planet, in the spirit of Bill McKibben’s Eaarth. But the Anthropocene is a useful word too, indicating as it does the extent to which we are permanently – even in geological terms – disrupting the recognizable Earth.

I do know that there is an undercurrent in civilization that recognizes the scale of the problem. More and more of us have an increasing sense that, at the deepest level, things are not as they should be. Imagining that the landscape of scars around our home might be multiplied across continents and oceans makes the hairs on the back of our neck stand up. Seeing roadkill in the context of a planet full of roads is heartbreaking. Contemplating the plastics and PFAS and pesticides that infiltrate blood and rainfall is terrifying. Noticing how much of the natural world around us has changed in our lifetime is overwhelming.

An undercurrent, according to Oxford Languages, is “an underlying feeling or influence, especially one that is contrary to the prevailing atmosphere and is not expressed openly.” The undercurrent that the Field Guide is meant to serve, then, is this awareness of vast, difficult, often irreversible transformations happening on our watch, and the quest for solutions.

All of this was brought into focus for me this week by a particularly spooky bit of research into an actual undercurrent, one that is vital to maintaining life as we know it.

As the 8-second video above indicates, the oceans have a circulation system. This system moves oxygen into the depths, carries nutrients upward to sustain the entire marine food web, and sequesters CO2 from the air into the abyss. This global “conveyor belt” is driven, in part, by the 250 trillion tons of dense, cold seawater sinking each year off the Antarctic coast and then creeping northward along the abyssal plain into the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans.

Another way of saying all this is that the cold Antarctic bottom water is essential for stabilizing much of life on Earth. Which is what makes this statement from Matthew England, lead researcher for a recent study, so hard to hear:

Our modeling shows that if global carbon emissions continue at the current rate, then the Antarctic overturning will slow by more than 40 percent in the next 30 years, and on a trajectory that looks headed towards collapse.

The cause is the rapid melting of Antarctic ice. The release of excess freshwater into the Southern Ocean dilutes its salinity and reduces its density, making it less likely to sink. As the input from Antarctic waters slows, so does the larger system. For a visual of this, imagine the consequences of a portion of an airport luggage conveyor belt slowing down. If one part slows, so does the rest of it.

Even if you’re skeptical of data-driven speculation on a grand scale, the risk potential here is catastrophic. Earth-shaking, really. An essential planetary function might lurch toward collapse in a generation. If true, in the time it takes to add another billion people and another degree or two of global heating (with all of their other consequences), the foundation of ocean ecosystems and fisheries will weaken and the removal of our excess CO2 from the atmosphere to the ocean deeps will be reduced. Worse, the increase in temperature of the Southern Ocean will intensify, melting more Antarctic ice in a feedback loop that would magnifies the process that slowed the conveyor belt in the first place. That feedback loop is what makes the researchers predict the possibility of total collapse.

Here’s what that ice mass loss in Antarctica has looked like over the last two decades:

While the authors note ominously that a slowdown of the Antarctic flow would “profoundly alter the ocean overturning of heat, fresh water, oxygen, carbon and nutrients, with impacts felt throughout the global ocean for centuries to come,” they don’t offer a list of those impacts. To start that list, you can a) think of slower ocean circulation as a climate change amplifier, and b) try to predict the knock-on effects of each item in the quotation.

An ocean that isn’t overturning (surface water sinking and bottom water rising) or moving in currents around the globe will be warmer, less oxygenated, more stratified, and deprived of nutrients. The oceans have so far absorbed about 40% of our Anthropocene CO2 production and about 90% of our fossil-fueled heat. Less overturning means more heat in surface waters and here on land, and more CO2 in the atmosphere.

I haven’t quite wrapped my head around the litany of impacts to life in the oceans, but it’s easy enough to worry about it while contemplating what does come to mind: reduced nutrients for plankton (which all marine life depends on), the expansion of dead zones due to heat and deoxygenation, reduced distribution of larval fishes that rely on ocean currents, and much more.

Potential consequences for human life are no less dire. The fate of fisheries, of course, but also intensified heat and other climate impacts. The more that Antarctic overturning circulation slows and gets caught in a feedback loop which increases the melting of Antarctic ice, the faster sea levels will rise. And then there’s agricultural losses around the globe because of rapid changes in weather and precipitation patterns. One study suggests that weakening of the circulation could shift tropical rainfall patterns a thousand kilometers northward. But we don’t need specific speculation to be concerned about agricultural production in a world destabilized by a hotter climate and a sluggish ocean. Farming and destabilized weather patterns don’t mix well, as is already becoming clear.

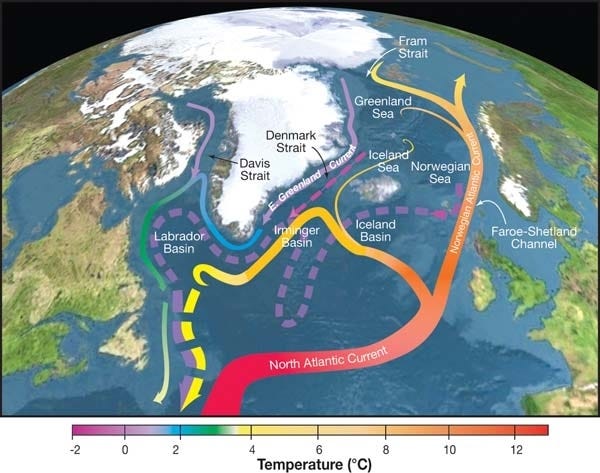

In related news, similar discussions have been going on for years about the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which is at its weakest point in the last thousand years. The AMOC moves heat from the equator to the Arctic, and is responsible for the mild weather in much of the North Atlantic region, including Europe and the eastern United States. It seems to be slowing because of climate-related intensified rainfall and increased meltwater from Greenland.

One oceanographer, talking about the AMOC slowdown, worried about future “food insecurity on a global scale.”

Because of its importance to the Intertropical Convergence Zone, AMOC slowdown would lead to large changes in precipitation in the tropics, including in Central and South America, India, South East Asia and parts of Africa,” Jones added. “Billions of people are reliant on crops grown in these regions, and changes in precipitation patterns could cause it to become even more difficult for these people to obtain food, leading to mass starvation and mass migration.”

You can watch an explainer video from two of the Australian researchers behind the Antarctic study in the video above. (It’s nice to hear some upbeat Australian accents, but the background music is weirdly cheerful.)

As Grist noted while covering this story, the IPCC had already predicted that “a slowing of marine currents can cause abrupt, and potentially irreversible, climate change on the timescale of a human lifespan,” yet the IPCC has not yet factored the impact of Antarctic meltwater on those marine currents into climate change models. Given how loud the U.N.’s alarm bells – the Code Red for humanity – are already ringing, it’s not hard to imagine the concern that will greet this latest study from the Antarctic.

Remember that this whole difficult conversation is rooted in the seemingly obscure melting of Antarctic ice. It is simply not human nature to worry about such things. If you were to rush out into the street and announce to a hundred people that Antarctic ice is melting so quickly that ocean currents will slow 40% in 30 years, and perhaps collapse this century, how many of them would care?

I’m reminded of John Muir’s oft-quoted wisdom – “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe” – but I can’t help but imagine that many threads in the Anthropocene tapestry, when tugged, will be worn, frayed, or broken. This is most clear when contemplating the rapid demise of biodiversity across the planet, as a recent Guardian article pointed out:

“We are currently losing species at a faster rate than in any of Earth’s past extinction events. It is probable that we are in the first phase of another, more severe mass extinction,” he said. “We cannot predict the tipping point that will send ecosystems into total collapse, but it is an inevitable outcome if we do not reverse biodiversity loss.”

To be clear, neither a mass extinction nor a collapse of ocean currents is inevitable. But both are scientifically likely if we don’t change the nature of civilization and get the good work done.

As I wrap things up here, I’m afraid that reading this essay has felt merely like doomscrolling, and you have my sincere apology for providing that experience. I am well aware that some of you are looking for a bright light amid the darkness, and that as a science communicator it’s far more useful for me to manage the landscape of fear than to merely describe it. Sometimes we need to talk about what we love about life as motivation for saving it. My recent two-part series, Memoir in a Handful of Birds, speaks to that approach.

But wonder and grief are our companions in an attentive Anthropocene life. And I’m trying to do two things this week: Explain the shocking seriousness of this new study on ocean circulation, and do so in the context of what motivated me to start writing the Field Guide exactly two years ago.

When I said at the start of this essay that the basic functions of the Earth were being disrupted by our actions, and that I think it’s vital that we recognize that reality, I meant it.

The good news, or at least the crux of the matter, is in the opening phrase of the quote from Matthew England: “if global carbon emissions continue at the current rate.” So maybe don’t worry about my insistence that we see the picture that’s even bigger than climate change. Just fight the good fight against climate chaos. You could argue that nothing else matters, and I won’t contradict you because what you’re doing is vital for life on Earth.

This is all very difficult stuff, I know, and it’s easy to feel helpless when faced with an oceanic problem. But the response to our fear of a slowing ocean circulation system should be clear and simple: Stop the burning of fossil fuels as quickly as possible. Leave them in the ground. Prohibit any new “carbon bomb” coal, oil, or gas projects, and stop prospecting for them. Force the world’s banks to stop funding the extraction of fossil fuels. Phase out the $5.9 trillion in subsidies (direct and indirect) spent on heating the world with fossil fuels. Elect politicians who will accelerate these processes.

In the meantime, let’s continue this conversation about life, how we think about it, and the consequences of that thinking. In doing so, we can turn the undercurrent into the mainstream.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Nature, carbon dioxide removal is, for the foreseeable future, a useless tool for dealing with the climate crisis. We must reduce emissions rather than count on some magic technology. It will likely be useful later on, but the only real task at hand right now is to stop producing greenhouse gases as quickly as possible.

From Inside Climate News, the world premiere of “Vespers of the Blessed Earth,” a great composer’s musical prayer, full of wonder and grief, for life amid the chaos of the Anthropocene. John Luther Adams’s composition has five movements: A Brief Descent into Deep Time, A Weeping of Doves, Night-Shining Clouds, Litanies of the Sixth Extinction, and Aria of the Ghost Bird. It’s a new work, with no recording available yet, but you can sample his previous nature-based compositions on his site.

From Wired, we should be asking questions about insect sentience and insect welfare, now that insect farming is becoming big business.

From Mongabay, part one of an excellent three-part series on small but vital “grassroots forest restoration projects carried out within isolated island ecosystems” in Hawaii, Costa Rica, and Brazil.

From the Times, the Biden administration has just proposed new rules that, if enacted, will likely ensure that two thirds of new cars sold by 2032 will be electric.

From E&E News, a summary of a bizarre but important federal court case that may redefine public access to U.S. public land. It involves four hunters and a stepladder. You’ve no doubt noticed on maps how much of the American West is cut up into a random checkerboard. Many of the squares are federal (public) land, while the rest are private, even if they completely surround the federal squares. “Corner-crossing” is the act of avoiding stepping on private land by climbing up and over a fence with a stepladder placed where the corners of two public squares meet. The lawsuit claims that corner-crossing is still trespassing.

From Rolling Stone, a great piece by Bill McKibben doing the math on climate change, fossil fuels, the Inflation Reduction Act, large-scale climate activism, and the path forward. Well worth the read.

Check out and share Not Too Late, the book (and the movement) working to help everyone understand climate chaos and the fight to reverse it. As they put it, “Not Too Late is the book for anyone who is despondent, anxious, or unsure about climate change and seeking answers.”

From Reasons to be Cheerful, did you know that the 3,000-mile East Coast Greenway is being built from Maine to Florida? The goal is to ensure public access to walking/biking trails up and down the coast. About a third is in place already, and funds from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law could accelerate the remainder. See the map at the Greenway’s website.

From bioGraphic, “Rogues of the Rainforest,” a long and fascinating article on how hotter, drier conditions in the tropics are giving liana vines an advantage over trees. This matters because tropical forests, already stressed in Anthropocene conditions, are storing less carbon, and the proliferation of lianas will worsen that trend.

The two oceans, the twin hearts. The atmospheric rivers of warm moist air moving above us like sinuous fire hoses, now impacting the Antarctic. The slower echoing response of the deep ocean currents in this billions year old dance of our planet's energy budget. This place is so achingly beautiful still, but sea levels are riding in China with unprecedented rapidity, The watchful satellites report ever increasing number of worldwide lightning strikes as this place is storing energy like an overcharged battery. We humans are wonderfully adaptable, but we can't cope with the loss of our sustaining mass agriculture and that's what's going to get us in the end. America in 2070 may have no Midwestern breadbasket. I fear the horseman Starvation is coming back if we don't start on the road of drastc negative population growth. Either we do it voluntarily or have it forced on us much more painfully. Reducing carbon production is absolutely necessary but it's only half. We must reduce our numbers and quickly. We're destroying this place.

Thanks, Jason.

Really thanks. It's in our nature, it seems, to avoid the horror, to focus on the often desperate needs in front of us: family, bills, what's for dinner. For a long time my approach has been to rub my face in the worst news and the emotions that follow; to use the facts as sandpaper against my inattention. Now? I've learnt the need to balance that with hope, as so many authors and activists are realising and sharing. ("Not Too Late" does look good.) My thanks to you is for being open to looking at and discussing the sandpaper, particularly in the way you have, with an open heart and apologies. It means - it feels - like another way to cope and move forward, this sharing. It is how we've always gotten through grief, isn't it?

This doing something for the planet, for tangled wet forests, for cow-faced manatees and curious grasshoppers, feels burned into my DNA. My sense is that it's the same for you, and so many others. Often it seems linked to a particular childhood - the seventies - when nature presented herself to roaming kids in glittering creeks and climbing trees, tadpoles and tangled brambles, and the admonition - "Be home by the time the streetlights come on" - left room for a bond and friendship and extended family that is unbreakable, one that leads to a profound sense of defend and nurture that you would have with any friend, with family.

Reasoning along these lines led more to start writing workshops into the felt reality of these familial kinships in the world. Creativity, deep ecology, a journey to connection. And I'm going on, I apologise, this is meant to be just a comment and a simple profound thankyou. Your contribution has stirred me up, which has been sorely needed. From here to where I last ran the workshops (and a local bookstore) there has been a biblical fire season, ditto floods, and lockdowns. And they are just the abstract labels, the signposts to emotions and traumas so many of us are trying to swim through, trying to keep a wet blanket over our heads and run through, smoke and tears in our eyes.

After a lot of work, substack has come to offer a path. I've been researching how best to start, how to be effective, but I'm scared. Of what? Of getting it wrong, perhaps. What I feel I have to share feels so much a part of my being that if people don't care, what does say of me? (I only just realised that and typed it quickly to outrun the fear.) Of remaining isolated. But I know that even on the possibility that what I have to offer may help in some way, that I have to try.

But where. To. Start.

So, thanks. Sorry for the unasked therapy session. But you've moved me to reach out and start in small way, and for that, too, I am grateful.