Hello everyone:

As a reminder, I’m celebrating the third anniversary of the Field Guide by offering a 20% discount paid subscription until May 1st. If my work here has value to you, and if you can afford it, I’d be honored to have you as a paid subscriber.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I wonder how many of you have a strong opinion about dams or hydropower. Depending on where we live, there may not seem to be much reason to have an opinion. Dams are ubiquitous – 90,000 inventoried in the U.S., but maybe as many as 400,000 total obstructions to river flow – but often invisible. We drive over them, we swim or fish cheerfully in their reservoirs, we see them as historical artifacts next to old mills, or we live too far away from the big canyon-blocking behemoths that might catch our attention. Nor do many of us know the source of the electrons – oil, gas, hydro, solar, wind? – that heat our homes and light our screens.

We were told through much of the 20th century that dams were noble creations, monuments to our ingenious command of earthly resources, necessary to a growing population, and beautiful in their powerful architecture. Later in the last century, some of us heard a different tune, one that grieved over the accelerating loss of vital, wild habitat as dams built with public money for private interests destroyed thousands of miles of the metaphor for life itself: the flow of a river.

Today, hydropower occupies a tenuous place in the heart of an environmentalist. Or really, it's more accurate to say hydropower means two very different things to the two types of Anthropocene environmentalists: the conservationists focused on the health of the living world, and the climate activists committed to reining in greenhouse gas emissions. Many of us like to wear both hats, of course, but I think the simplicity of the emissions = climate equation has seduced a lot of activists away from the messier and more difficult problems of deforestation, biodiversity loss, and extinctions. (Too few of us seem to recognize that a) climate chaos is a subset of the larger threats-to-life problem, b) forests are as central to climate as emissions, and c) fixing emissions will not revitalize the bulldozed world.)

We live in a moment in which dams are the destroyers of rivers but a relative boon to the climate. In which dams kill, but do it locally and cleanly, without fanning the flames of a burning world.

I have long been in the camp of those who see dams primarily as antithetical to life. I’ve spent a lot of time and miles in a canoe, and have come to see dams as a brutal occupying force in the peaceful nations of water. Dams amputate rivers. They imprison flowing water and harm the innumerable aquatic and terrestrial habitats and ecosystems that rely upon it. They flood valleys and isolate populations of fish and shellfish, accelerating extinctions. They turn the flow of life into segmented commodities, whether to sell electricity or stabilize river flow for shipping. They end migratory journeys, destroy ecological connections, drown riverine and riparian habitats, and make rivers hotter and stagnant and less oxygenated.

As flow is interrupted, nutrients that connect land and sea are orphaned at the bottom of reservoirs or unable to pass upstream. That flow of nutrients should be flowing both ways, with anadromous fish and catadromous eels returning from ocean habitats that stretch over thousands of square miles, funneling ocean wealth deep into rivers and streams. Here in Maine, for example, where 27% of our power comes from hydro, uncounted millions of migratory fish (eels, shad, salmon, smelts, alewives, blueback herring, striped bass) once fed the inland birds, mammals, and aquatic species who in turn fed the forests, lakes, and ponds. Dams here, as elsewhere, have reduced those millions to trickles.

Dams trap life-giving sediment in reservoirs rather than sending it downstream where it’s needed to avoid the erosion of floodplains and deltas. Those reservoirs also lose too much of their stored water to evaporation, especially in hot tropical regions. In fact, all the evaporation from reservoirs around the globe is about the same as all the water consumed by the world’s cities. And the rotting vegetation at the bottom of reservoirs produces 1.3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. “Emissions from some reservoirs,” as The Revelator points out, “can even rival that of fossil fuel power plants.” And then there’s the massive, emissions-heavy concrete construction of the dam itself.

“There’s a reason John McPhee placed them at conservationists’ ‘absolute epicenter of Hell on earth,’” writes Ben Goldfarb in Eager. “They gut ecosystems.” Dam destruction is local, yes, but when dams are everywhere so are their impacts. (Remember that there are hundreds of thousands of them in the U.S. alone.) Populations of freshwater species around the planet have declined an average of 84% since 1970, which is far more than declines seen in terrestrial or marine species. And keep in mind that rivers were not in particularly good shape in 1970, as we’d already been damming and polluting them for most of a century.

To cite just one example: The most imperiled animals in North America, as I wrote in a piece titled The Liver of the River, are freshwater mussels. They’re vital for river health, beautiful to look at, strange in their sex lives, and hanging on by a thread in the incredibly biodiverse but heavily dammed southeastern rivers where they were once abundant.

But hydroelectric dams have powered modern human activity in a relatively reliable, nontoxic manner for more than a century. Much of what we call modern civilization owes its existence to dams and their capacity to channel the Earth’s rivers through turbines. Dams keep the lights on, and probably power the factories that make canoes. The beloved swimming hole in my little town sits behind a small dam. As of 2020, hydropower amounted to about 17% of the global energy supply. Even today, as solar and wind energy production increases rapidly, hydropower remains the largest source of renewable energy by far, providing about half of the global supply.

Hydro is the “white coal” that helped power the early rise of industry and the cultural dominance of electricity, alongside the burning of coal and oil. Except in times of drought or dam failure, it has been a largely stable power source, and one that doesn’t require a global infrastructure to move a dirty power source from continent to continent.

The phrase “white coal” was coined by a French engineer in the late 19th century, inspired by the reliability and permanence of the snow-covered Alpine glaciers whose run-off he was capturing to power industry. The phrase caught on, perhaps because of the white froth of falling water, and spread to the U.S., where the rapid expansion of hydro grew hand-in-hand with the transformation of the country by the infrastructure of electricity.

A history lesson from the Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance explains that the popularity of hydro was due in part to how non-polluting it was, and in part to its profitability for men of industry, who were pleased by the control hydro provided them over profits, labor, and the rivers:

Running water was deemed “white coal” – a source of power that was renewable, did not require costly transportation by rail, and could not be disrupted by unionization efforts or labor struggles in the mines. Waterpower was also clean and did not pollute cities with dark clouds of smoke. As one North Carolinian explained, “There will be no coal to go in, no ashes to go out, no gas, no soot, no dirt.” Because water could be stored behind dams until there was a demand for energy, industry leaders considered hydroelectric power the most efficient use of their waterways. Letting rivers run wild was a waste of the region’s abundant resources…

We still largely see rivers as resources rather than life itself. Hydro stores rain, then regulates its downhill flow, “creating essentially a water bank from which people can withdraw when the need arises,” as one sanguine analysis describes it. It turns a natural feature of the Earth into energy storage and production without heat or smoke. Local and global water cycles are altered but not eliminated. In this sense, hydropower is ideal in regions with heavy rainfall, like the tropics, where nations still developing robust energy infrastructure can build long-lasting reliable sources.

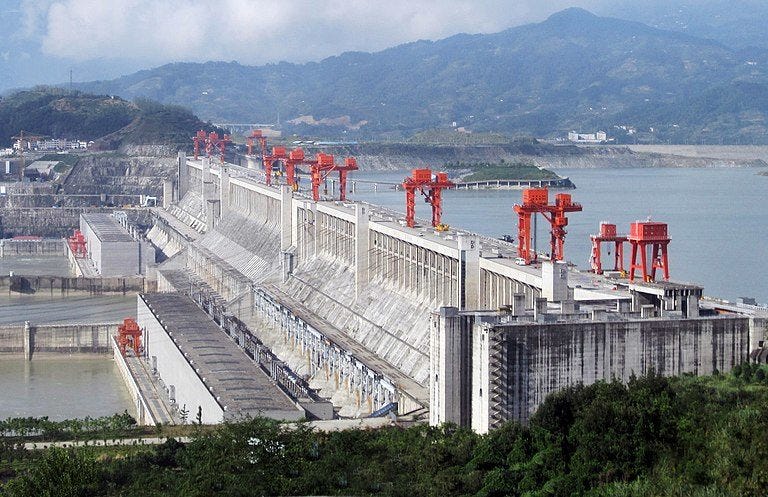

China, in particular, has been developing an extraordinary amount of hydropower capacity, including the 1.3-mile-long, 22.5-megawatt Three Gorges Dam. In 2022, China produced enough hydroelectricity to meet the entire world’s energy needs back in 1950. By the end of 2023, China’s hydro capacity was 422 terawatts, more than four times that of the U.S. Brazil, meanwhile, derives nearly 63% of its power from hydro, while several small nations (some, admittedly, with incomplete power grids) rely on hydro for 99-100% of their electricity. (You can explore these numbers and more here.)

As a power source, hydro is nicely flexible, able to ramp up or down as necessary with easy adjustments to the flow. As we steer away from reliable but toxic fossil fuels, there’s a lot of pressure to anchor solar- and wind-powered energy grids with another steady source – what’s called “clean firm power” – that also works well alongside these other sources. There are other options for large-scale stability on the horizon, like battery storage and advanced geothermal, but they might require decades to catch up to hydro.

In the U.S., though, only 3% of dams produce electricity, providing 6.3% of our electricity. The rest, assuming they’re doing something useful, stabilize river depth for navigation and control floods, protecting human development from the natural spread of rushing water when rain becomes riot. At a large scale, dams can do for civilization what nature (even the miraculous beavers) cannot, storing vast quantities of water which can be transferred as needed to cities and agricultural areas hundreds of miles away.

In other words, dams and hydropower have long been essential to living the lives we like to live.

Efforts to blunt the ecological costs of dams and hydropower are widespread, especially in trying to allow fish passage around the blockades, but these have largely been insufficient to protect or revive the life-giving waters to anything like their previous abundance. The work continues, though, and is getting better.

These trade-offs with hydropower are a feature of the Anthropocene, one that we’re still very much wrestling with. We want to protect and heal the living world, but we need to feed and fuel billions of people. We want to stop cooking the planet, but we don’t want to change how we live, other than to allow the billions of impoverished people to live comfortable middle-class lives. We should be devoting our best minds, and our own quiet souls, to figuring out how to live with less. Until that happens, though, we need much, much more energy available for an equitable civilization, but that human equity often ignores the needs of the rest of life on Earth, even with an energy source as “clean” as hydropower.

Moreover, climate chaos is making things more complicated. CO2-choked skies, hotter seas, and more chaotic weather are revealing new limitations of hydropower, even as pressure intensifies to increase its place in the global renewable energy mix. As we seem to be triggering tipping points in Earth systems, like disrupting ocean currents or accelerating polar ice loss, the chaos in global weather will worsen exponentially, making hydropower an even less sure bet.

So where does hydro fit into an Anthropocene future? It's complicated.

According to Fatih Birol, the Executive Director of the International Energy Agency, “hydropower is the forgotten giant of clean electricity, and it needs to be put squarely back on the energy and climate agenda if countries are serious about meeting their net zero goals.” But hydropower’s share of the global energy supply is declining as energy demand goes up, as old unsafe dams come down, as solar and wind power infrastructure spreads across the world, and as the movement grows to tear down dams that do too little and harm too much. Ecologically (and ethically), we can no longer afford to build dams without good reason, or design dams without fully integrating new protections for the lives they interrupt.

I mentioned above that my small coastal Maine town has a beloved swimming hole created by a small dam. A few years back, the town had to decide whether to repair it as it was, repair with the added cost of building a much more effective fish ladder for migratory alewives and other species, or remove it to prioritize restoring original habitat over the swimming hole and water levels for lakefront homes. The town rallied behind the second, more expensive option, which was a compromise of sorts for human and more-than-human interests.

There are millions of decisions like this to be made around the world about what to do with these disruptions to the flow of life. It's a time of reckoning for dams and hydropower, and I’ll do my best to figure some of that out and explain it to you next week. There is reason for some cautious optimism on both the energy and ecology sides of this debate, but as always in the Anthropocene that optimism takes place within a wider experience of ecological grief.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From NPR, an article on wildlife rehab in D.C. caring for baby squirrels and other everyday urban wildlife. I offer it to you here not because it’s a particularly important story, but because of the vital environmental ethic at work here, one expressed beautifully by the executive director of the rehab center:

"It's not like you're born with a finite amount of compassion — once you use it up, that's it, you're a jerk. It's not like that. The more compassionate stuff you do, the more kind you become," Monsma says… "We have changed our environment to make life very pleasant and efficient and comfortable for us," he says. Things like roads, cars, lawns, and lawnmowers make life easier for people, but much tougher for wild animals.

A shout-out here to Mongabay, one of the best and most comprehensive sites online for environmental reporting. (Thanks to

for the reminder.) I’ve neglected Mongabay in recent months, but a quick glance at the site’s homepage shows just how much incredible reporting they do: an oil spill in Peru, a conflict between people and fishing cats in Bangladesh, the fate of an anti-deforestation law in the EU, IKEA’s role in deforestation of Romanian old growth, “living shoreline” defensive strategy on the eroding coast of downeast Maine, and much much more. Check out Mongabay’s great work, and support them if you can.From Mongabay, the Earth’s oceans have suffered another global coral bleaching event, affecting corals in the waters of at least 54 countries and as deep as 200 feet (60 meters). This looks to be the worst/largest bleaching event ever recorded, and by all accounts is a sign of what’s to come as the oceans heat faster than any computer model had predicted, as global deforestation and industrial emissions continue to increase.

From

of here on Substack, a new directory called HOME that brings together all of the Substack nature-focused newsletters for you to peruse and check out. Rebecca is still putting the final touches on the directory, but you can peek in and see the incredible scope of what she’s assembled and what is available, across the world and across the spectrum of nature-focused writers. Rebecca has done us all a great service, so don’t forget to thank her.For anyone interested in contributing to science from the comfort of your home computer, take a deep dive into the myriad opportunities in the Zooniverse. The link here is to 47 nature-themed projects, which range from Tag Trees (a restoration project) to Name That Neutrino (at the South Pole). You can transcribe nest records for wrens or Italian hydrological records, or you can identify spider crabs or frogs in Australia, corals in the Gulf of Mexico, elephants in South Africa, or critters in the U.S. southwest.

Thursday was World Penguin Day, and if you want to support excellent work being done in a decades-long project to assess penguin populations in the Antarctic, please support Oceanites. They perform a vital service in a very hard-to-access part of the globe.

If you don’t already receive the Climate Forward newsletter from the Times, I recommend it. This week, it provides an overview of the push for a global plastics treaty and the pushback from an army of lobbyists trying to convince treaty delegates that restricting plastics production will be bad for humanity. Also, the newsletter provides a comprehensive update on all the remarkable achievements in rule-making by the Biden administration to shift the U.S. toward a rational relationship with the living world, whether through emissions reductions, land conservation, and chemical safety.

From AskNature, an organization devoted to the science and art of biomimicry, in which the close study of nature teaches us how to develop better and more environmentally-friendly technologies, a lesson learned from pufferfish on how to design a better water purifier.

From Yale e360, which is always a reliable and well-written source, two stories: An update on efforts to increase the ocean’s potential for sequestering CO2, and a push to ban fishing for eels in Europe, where the species has long been in severe decline. For more on the eel story, see my piece Born Into Mystery.

“Too few of us seem to recognize that a) climate chaos is a subset of the larger threats-to-life problem, b) forests are as central to climate as emissions, and c) fixing emissions will not revitalize the bulldozed world.”

A sizable subset of threat to life dynamics exist. But they are all ancillary compared to emissions. The forest and bioregional Eco habitat systems around the globe need to be rebuilt and re-wilded, from a deep ecology perspective. Not having anything to do with climate change or weather chaos. Simply to restore the chance of complex life form of surviving.

I will say that it’s number two priority after a genuine effort to reverse our self inflicted climate catastrophe. Please don’t correlate to two. They are completely separate issues other than they both threaten existence of many lifeforms. The climate situation threatens existence of all complex multi celled organisms. Don’t get yourself. We could easily become Venus or Mars, depending on how things shake out. Most likely a larger less dense atmosphere of Venus.

Actually Jason, I am very happy to correct you on your perspective about cooperation between the faiths as that "firewall" doesn't exist on this issue of creation. I was on a Zoom meeting with Interfaith Power & Light this morning addressing local TX energy issues. We work with GreenFaith as well. ALL of our orgs. are multi-faith. LSM is open to all as long as they believe a higher power put all in motion so we have 2 members in TX who just say they are "spiritual" and do not attend any church or identify with a denomination. Our LSM TX chapter has 7 leadership positions and 2 are held by non-Catholics. Although the US Catholic church has not embraced what we call Care for Creation as aggressively as the other pro-life issue, the rest of the world Catholics have embraced it and are also working with other faiths for our "common home". You are correct, this is NOT "policy" nor "liberal"; it is a moral issue that many faiths (more so outside the US) are addressing. If you have 90 minutes to spare, watch THE LETTER (free on YouTube); the only documentary ever created at the request of the Vatican. Not one protagonist is Catholic but Hindu, Muslim, indigenous belief and agnostic and Pope Francis sat with all of them to listen to their first hand experience with the climate crisis. As an environmentalist since early childhood, I recognized long ago that to change how we treat our Mother Earth was going to require a true change in heart (not mind) for many people because altruistic behavior based on logic and reason rarely wins out in America. May this info. provide you with more hope.